38 million people had HIV/AIDS in 2020. A couple of decades ago, the chances of surviving more than ten years with HIV were slim. Today, thanks to antiretroviral therapy (ART), people with HIV/AIDS can expect to live long lives.

ART is a mixture of antiviral drugs that are used to treat people infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). ART is an essential player in making progress against HIV/AIDS because it saves lives, allows people with HIV to live longer, and prevents new HIV infections.

Since the first version of ART was introduced in the late 1980s, the treatment has saved millions of lives.

The chart here shows the annual number of deaths from HIV/AIDS, and the number of deaths averted as a result of ART.

Globally, 1 million people died from HIV/AIDS in 2016; but even more deaths – 1.2 million – were averted as a result of ART. Without ART, more than twice as many people would have died from HIV/AIDS.

ART not only saves lives but also gives a chance for people living with HIV/AIDS to live long lives. Without ART very few infected people survive beyond ten years.1

Today, a person living in a high-income country who started ART in their twenties can expect to live for another 46 years — that is well into their 60s.2

While the life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS in high-income countries has still not reached the life expectancy of the general population, we are getting closer to this goal.3

The combination of antiretroviral drugs which make-up ART have progressively improved. Recent research shows that a person who started ART in the late 1990s would be expected to live ten years less than a person who started ART in 2008.4 This increase goes beyond the general increase in life expectancy in that period and reflects the improvements in ART — fewer side effects, more people following the prescribed treatment, and more support for the people in need of ART.

There is considerable evidence to show that people who use ART are less likely to transmit HIV to another person.5 ART reduces the number of viral particles present in an HIV-positive individual and therefore, the likelihood of passing the virus to another person decreases.

In 2011, the journal Science named a study that found that ART reduced the risk of HIV transmission between couples by 96% as its “Breakthrough of the Year”.6 Many other studies have now shown similar findings, with a range of reduction in transmission attributable to ART depending on location and groups studied.7 A study from British Columbia, for example, showed that with every 10% increase in ART coverage there was an 8% decrease in new diagnoses of HIV.8

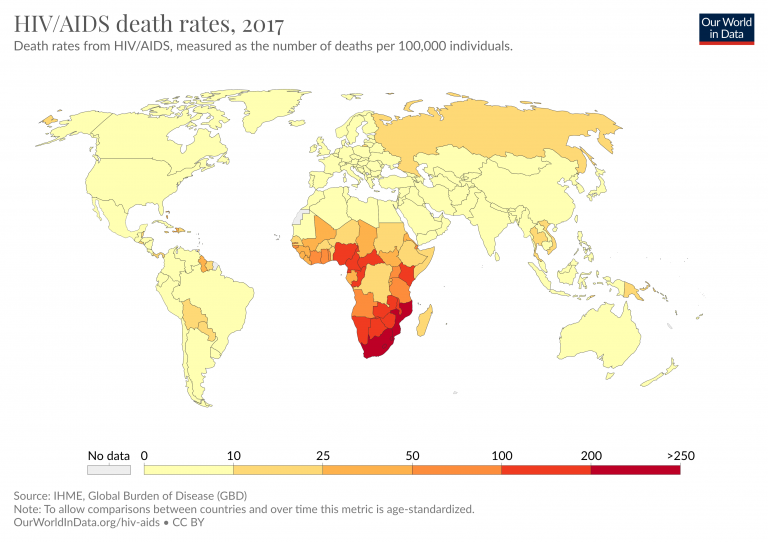

The number of people who receive ART has increased significantly in recent years, especially in African countries where the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is the highest. You can see this in the map. In 2005 only 2 million people received ART; by 2018 this figure has increased more than ten-fold to 23 million.9

But still, 23 million is only 61% of HIV-positive individuals. It means that 14.6 million people who could benefit from the life-saving treatment currently don’t.

To increase ART coverage we need to first improve access to testing for HIV status. In 2018, 79% of people living with HIV knew their status. This means 1-in-5 people living with HIV are unaware.10 And awareness is also not enough. In Sub-Saharan Africa among people who are HIV positive only 57% go on to complete required pre-treatment assessments.11 And of those who should start ART only 66% do.12

Stigmatization of people who have HIV/AIDS also leads to a decrease in engagement with care, treatment, and prevention services.13

Due to its success ART is sometimes called the Lazarus drug, referring to the biblical story about a man raised from the dead.14 With access to ART, HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence. But to make progress against HIV/AIDS and fully benefit from the potential of ART treatment we need to increase HIV/AIDS awareness and improve access to ART.