Across the world women tend to take more family responsibilities than men. As a result women tend to be overrepresented in low paying jobs where they are more likely to have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

These two facts – documented in the previous post on the gender pay gap – are often used to claim that, since men and women tend to be endowed with different tastes and talents, it follows that most of the observed gender differences in wages stem from biological sex differences. In this blog post I examine the evidence behind these claims.

In a nutshell, here’s what I find:

- There is evidence supporting the fact that, statistically speaking, men and women tend to differ in some key aspects, including psychological attributes that may affect labor-market outcomes.

- There is no consensus on the exact weight that nurture and nature have in determining these differences, but whatever the exact weight, the evidence does show that these attributes are strongly malleable.

- Regardless of the origin, these differences can only explain a modest part of the gender pay gap.

Some context regarding the gender distribution of labor

Before we get into the discussion of whether biological attributes explain wage differences via gender roles, let’s get some perspective on the gender distribution of work.

The following chart shows, by country, the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work, including tasks like taking care of children at home, housework, or doing community work. As can be seen, all over the world there is a radical unbalance in the gender distribution of labor – everywhere women take a disproportionate amount of unpaid work.

This is of course closely related to the fact that in most countries there are gender gaps in labor force participation and wages.

“Boys are better at maths”

Differences in biological attributes that determine our ability to develop ‘hard skills’, such as maths, are often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap.1 Do large gender differences in maths skills really exist? If so, is this because of differences in the attributes we are born with?

Let’s look at the data.

Are boys better in the mathematics section of the PISA standardised test? One could argue that looking at top scores is more relevant here, since top scores are more likely to determine gaps in future professional trajectories – for example, gaps in access to ‘STEM degrees’ at the university level.

The chart below shows the share of male and female test-takers scoring at the highest level on the PISA test (that’s level 6). As we can see, most countries lie above the diagonal line marking gender parity; so yes, achieving high scores in maths tends to be more common among boys than girls. However, there is huge cross-country variation – the differences between countries are much larger than the difference between the sexes. And in many countries the gap is effectively inexistent.2

Similarly, researchers have found that within countries there is also large geographic variation in gender gaps in test scores. So clearly these gaps in mathematic ability do not seem to be fully determined by biological endowments. 3

Indeed, research looking at the PISA cross-country results suggests that improved social conditions for women are related to improved math performance by girls.4

Not only statistical gaps in test scores vary substantially across societies – they also vary substantially across time. This suggests that social factors play a large role in explaining difference between the sexes.

In the US, for example, the gender gap in mathematics has narrowed in recent decades.5 And this narrowing took place as high school curricula of boys and girls became more similar. The following chart shows this: In the US boys in 1957 took far more math and science courses than did girls; but by 1992 there was virtual parity in almost all science and math courses.

More importantly for the question at hand, gender gaps in ‘hard skills’ are not large enough to explain the gender gaps in earnings. In their review of the evidence, Blau and Kahn (2017)6 conclude that gaps in test scores in the US are too small to explain much of the gender pay at any point in time.

So, taken together, the evidence suggests that statistical gaps in maths test scores are both relatively small and heavily influenced by social and environmental factors.

“It’s about personality”

Biological differences in tastes (e.g. preferences for ‘people’ over ‘things’), psychological attributes (e.g. ‘risk aversion’) and soft skills (e.g. the ability to get along with others) are also often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap.

There are hundreds of studies trying to establish whether there are gender differences in preferences, personality traits and ‘soft skills’. The quality and general relevance (i.e. the internal and external validity) of these studies is the subject of much discussion, as illustrated in the recent debate that ensued from the Google Memo affair.

A recent article from the ‘Heterodox Academy‘, which was produced specifically in the context of the Google Memo, provides a fantastic overview of the evidence on this topic and the key points of contention among scholars.

For the purpose of this blog post, let’s focus on the review of the evidence presented in Blau and Kahn (2017) – their review is particularly helpful because they focus on gender differences in the context of labor markets.

Blau and Kahn point out that, yes, researchers have found statistical differences between men and women that are important in the context of labor-market outcomes. For example, studies have found statistical gender differences in ‘people skills’ (i.e. ability to listen, communicate, and relate to others). Similarly, experimental studies have found that women more often avoid salary negotiations, and they often show particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotability. But are the origins of these differences mainly biological or are they social? And are they strong enough to explain pay gaps?

The available evidence here suggests these factors can only explain a relatively small fraction of the observed differences in wages.7 And they are anyway far from being purely biological – preferences and skills are highly malleable and ‘gendering’ begins early in life.8

Here is a concrete example: Leibbrandt and List (2015)9 did an experiment in which they assessed how men and women reacted to job advertisements. They found that although men were more likely to negotiate than women when there was no explicit statement that wages were negotiable, the gender difference disappeared and even reversed when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable. This suggests that it is not as much about ‘talent’, as it is about norms and rules.

“A man should earn more than his wife”

The experiment in which researchers found that gender differences in negotiation attitudes disappeared when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable, emphasizes the important role that social norms and culture play in labor-market outcomes.

These concepts may seem abstract: What do social norms and culture actually look like in the context of the gender pay gap?

The reproduction of stereotypes through everyday positive enforcement can be seen in a range of aspects: A study analyzing 124 prime-time television programs in the US found that female characters continue to inhabit interpersonal roles with romance, family, and friends, while male characters enact work-related roles.10 In the realm of children’s books, a study of 5,618 books found that compared to females, males are represented nearly twice as often in titles and 1.6 times as often as central characters.11 Qualitative research shows that even in the home, parents are often enforcers of gender norms – especially when it comes to fathers endorsing masculinity in male children.12

Of particular relevance in the context of labor markets, social norms also often take the form of specific behavioral prescriptions such as “a man should earn more than his wife”.

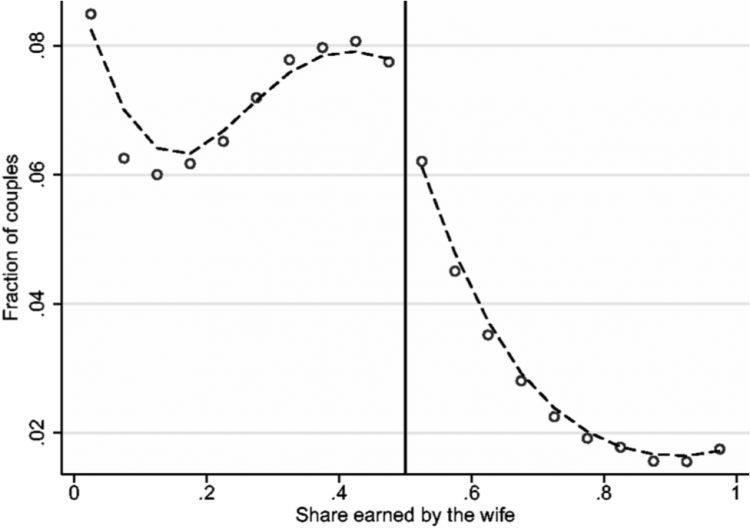

The following chart depicts the distribution of the share of the household income earned by the wife, across married couples in the US. Consistent with the idea that “a man should earn more than his wife”, the data shows a sharp drop at 0.5, the point where the wife starts to earn more than the husband. This is the result of two factors. First, it is about the matching of men and women before they marry – ‘matches’ in which the woman has higher earning potential are less common. And second, it is a result of choices after marriage – the researchers show that married women with higher earning potential than their husband often stay out of the labor force, or take ‘below-potential’ jobs.13

The authors of the study from which this chart is taken explored the data in more detail and found that in couples where the wife earns more than the husband, the wife spends more time on household chores, so the gender gap in unpaid care work is even larger; and these couples are also less satisfied with their marriage and are more likely to divorce than couples where the wife earns less than the husband.

The empirical exploration in this study highlights the remarkable power that gender norms and identity have on labor-market outcomes.

Distribution of income share earned by the wife across married couples in the US – Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan (2015)14

So what?

Does it actually matter if social norms and culture are important determinants of gender roles and labor-market outcomes? Are social norms in our contemporary societies really less fixed than biological traits?

Based on the available research, I believe the answer to these questions is yes, and yes. There is evidence that social norms can be actively and rapidly changed.

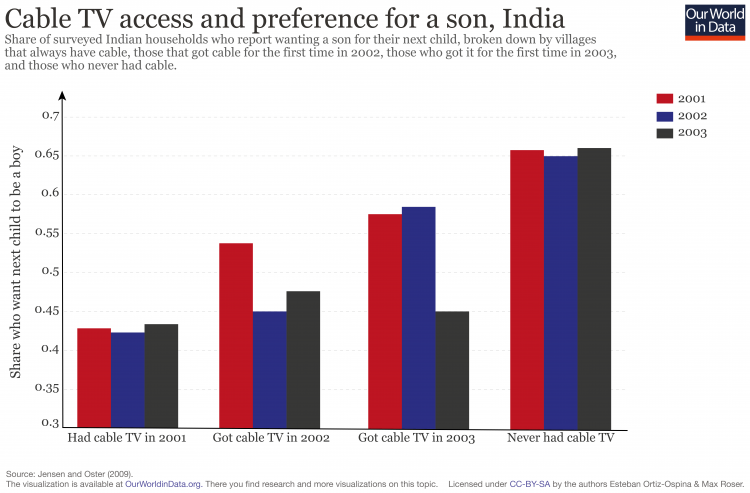

Here is a concrete example: Jensen and Oster (2009)15 find that the introduction of cable television in India led to a significant decrease in the reported acceptability of domestic violence towards women and son preference, as well as increases in women’s autonomy and decreases in fertility.

Of course, TV is a small aspect of all the big things that matter for social norms. But this study is important for the discussion because it is hard to study how social norms can be changed. TV introduction is a rare opportunity to see how a group that is exposed to a driver of social change actually changes.

As Jensen and Oster point out, most popular cable tv shows in India feature urban settings where lifestyles differ radically from those in rural areas. For example, many female characters on popular soap operas have more education, marry later and have smaller families than most women in rural areas. And, similarly, many female characters in these tv shows are featured working outside the home as professionals, running businesses or are shown in other positions of authority.

The bar chart below shows how cable access changed attitudes towards the self-reported preference for their child to be a son. As the authors note, “reported desire for the next child to be a son is relatively unchanged in areas with no change in cable status, but it decreases sharply between 2001 and 2002 for villages that get cable in 2002, and between 2002 and 2003 (but notably not between 2001 and 2002) for those that get cable in 2003. For both measures of attitudes, the changes are large and striking, and correspond closely to the timing of introduction of cable.”

To conclude: The evidence suggests that biological differences are not a key driver of gender inequality in labor-market outcomes; while social norms and culture – which in turn affect preferences, behavior and incentives to foster specific skills – are very important.

This matters for policy because social norms are not fixed – they can be influenced in a number of ways, including through intergenerational learning processes, exposure to alternative norms, and activism such as that which propelled the women’s movement.17