- Child maltreatment is common and takes many forms. From physical or emotional abuse, to child labor and other practices that violate their most basic rights.

- Violence against children, at home, schools, or in the broader society, affects educational outcomes. It affects whether children are able to attend and remain in school, as well as whether they make progress in terms of learning outcomes. And at the same time, educational outcomes affect violence – education has been identified as a tool to reduce violence against children.

- In this post we focus on the importance of child maltreatment specifically in the context of children’s education and give an overview of the empirical evidence.

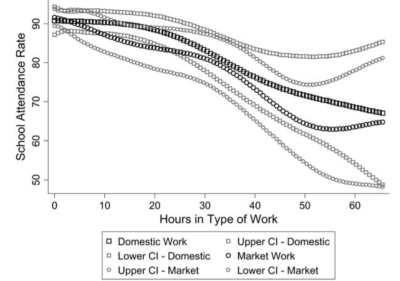

Child labor constitutes in most situations a violation of children’s rights, as it is often linked to several forms of abuse and harm. Specifically in the context of education, child labor is often linked to poor educational outcomes. The chart here, from Schultz and Strauss (2008),1 shows evidence for this. It plots school attendance rates for children aged 10–14 years olds, against total hours worked in the last week (by type of work) with 95 percent confidence intervals (labeled CI and plotted in lighter shades).

Children who work more hours tend to attend school less frequently. And the steepest segments of the pictured curves are in the range 20-45 hours, which suggests — as one would naturally expect — that it is most difficult for a child to attend school when approaching full-time work.

This evidence also shows that there is no significant difference between children engaged in domestic or marketed work.

School Attendance vs. Hours Worked – Schultz and Strauss (2008) 2

The chart above shows the relationship between school attendance and hours worked using micro data, which means that the authors investigate the relationship across individual households. A similar pattern can also be seen in the data if we look at the corresponding country-level macro variables: In countries where children tend to work longer hours, it is more common that working children remain out of school. The interactive chart below shows this by plotting country-level average hours worked by children against share of working children who are out of school.

These correlations on the micro and macro level are of course not enough to establish a causal relationship. There are many potential economic and cultural factors that simultaneously influence both schooling and work decisions; and in any case, the direction of the relationships is not obvious—do children work because they are not attending school, or do they fail to attend school because they are working?

A number of academic studies have tried to investigate whether there is indeed a causal relationship by attempting to find a factor (an ‘instrumental variable’) that only affects whether a child works without affecting how the family values other uses of the child’s time. These studies – like Rosati & Rossi (2003) or Gunnarsson, Orazem & Sanchez (2006) – suggest that there is indeed a causal relationship: work often does determine whether a child remains in, or drops out of, school.3 4

Children who are victims of physical or psychological abuse tend to have worse educational outcomes; and while evidence supporting a causal link is scarce, it is important to pay attention to these correlations.

A recent study used detailed household surveys from South Africa and Malawi to document the prevalence of violent discipline and subsequent changes in school progress among the affected children. The study found that children who were exposed to psychological and physical violence for discipline were more likely to have dropped out of school upon follow-up (Sherr et al. 2015).5

Other studies have found that violence against children also correlates with poor educational outcomes in the long run. In rich countries, for example, studies have found that individuals who are exposed to sexual and physical abuse in childhood are more likely to drop out of college (Boden et al. 2007 and Duncan 2000).6

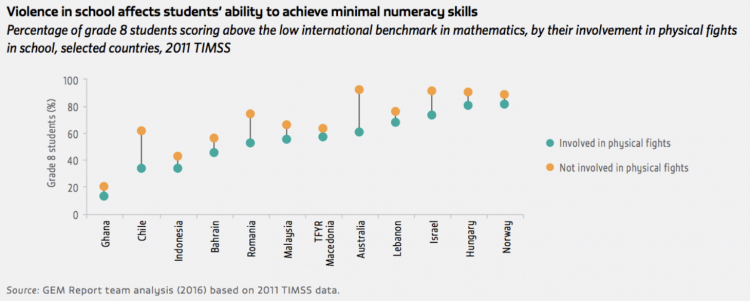

These correlations also extend to other forms of violence and other types of educational outcomes. Within schools, for instance, violence between children tends to go together with poor learning outcomes. The following chart provides an example of this correlation. It shows, for a number of countries, the percentage of grade 8 students scoring above the low international benchmark in the TIMSS mathematics test, by their involvement in physical fights in school. Numeracy results were consistently higher among children not involved in physical fights in school.

School fighting vs Minimum proficiency in maths – UNESCO (2016)7

Physical and psychological abuse are often linked to negative effects on mental and physical health. For example, it has been documented that anxiety and depression tend to arise more frequently among children who are abused.8

Again, these correlations do not imply causation. But there are good reasons to take them seriously. The World Development Report (2018) notes that toxic stress in the early years can undermine lifelong health, learning, and behavior, because the hormones associated with the fight-or-flight response, such as cortisol, can inhibit physical growth and the children’s susceptibility to illness. It is also the case that these hormones can impair the development of neural connections in parts of the brain that are critical for learning.

The following is an example of the type of brain development problems that scientists attribute to sensory neglect in early childhood. The source is Perry (2002).9 The CT scan on the left is an image from a healthy three year old with a typical head size (at the 50th percentile of the distribution). The image on the right is from a three year old child suffering from ‘severe sensory-deprivation neglect’ – minimal exposure to language, touch, and social interactions. The brain of the child on the right is significantly smaller than average (3rd percentile) and has signs of deterioration (cortical atrophy).

Of course, this comparison is just an illustration, and it is hard to know with certainty whether the observed differences in brain size can be fully attributed to sensory-deprivation neglect. However, Perry finds that the average head size among a group of 40 children who had suffered sensory neglect is below the 5th percentile in the distribution – and while some recovery in brain-size was observed after children were removed from the neglectful environment, in most cases the gaps remained significant.

These findings are relevant to education because brain malleability is much greater earlier in life, and brain development is sequential and cumulative; which means that brain deterioration can lead to permanent impairments on skill acquisition.10

Brain scan from a non-neglected child with an average head size (left) in comparison to a scan from a child suffering from severe sensory-deprivation neglect (right) – Perry (2002)11

The interaction between violence and education operates in both directions, which means education can be used as an instrument to reduce the prevalence of violence. In Uganda, for example, a programme that provided life skills and vocational training for girls who had been forced into sexual acts, led to substantially fewer of these girls being victims of sexual abuse – an impact largely attributed to acquired skills (Bandiera et al. 2017).12

Similarly, parenting interventions that promote skills and knowledge among parents have shown positive effects on domestic violence. In Liberia, for example, a program that provided training in positive parenting and non-violent behaviour reduced violent punishment drastically (Sim et al. 2014).13

Evidence from a range of countries shows that there is a correlation between violence against children and educational outcomes. These correlations are strong and hold for different forms of victimization. In some cases there is evidence of causal relationships; but even in contexts where causality is not clear, these correlations are important because they show that different forms of hardship often converge on some of the most vulnerable members of society.