People across the world are becoming increasingly concerned about climate change: 8-in-10 people see climate change as a major threat to their country.1

As I have shown before, food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

There is rightly a growing awareness that our diet and food choices have a significant impact on our carbon ‘footprint’. What can you do to really reduce the carbon footprint of your breakfast, lunches, and dinner?

‘Eating local’ is a recommendation you hear often – even from prominent sources, including the United Nations. While it might make sense intuitively – after all, transport does lead to emissions – it is one of the most misguided pieces of advice.

Eating locally would only have a significant impact if transport was responsible for a large share of food’s final carbon footprint. For most foods, this is not the case.

GHG emissions from transportation make up a very small amount of the emissions from food and what you eat is far more important than where your food traveled from.

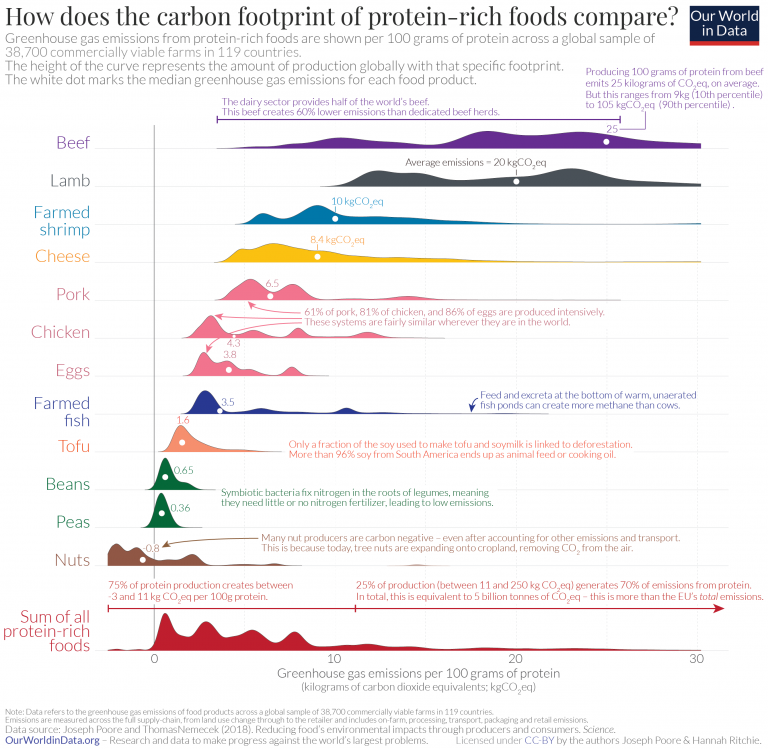

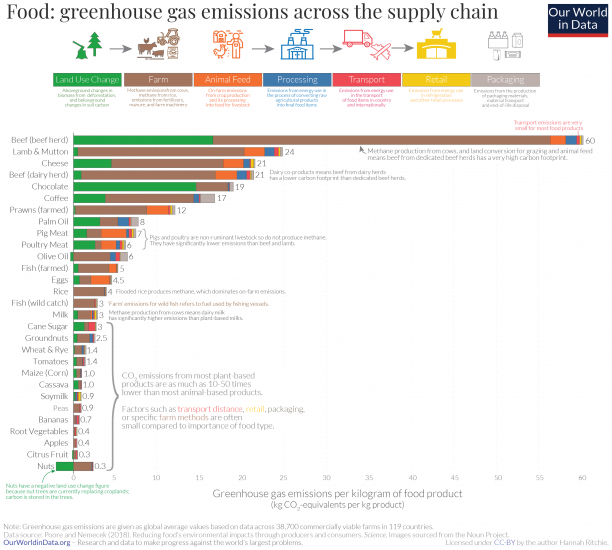

In the visualization we see GHG emissions from 29 different food products – from beef at the top to nuts at the bottom.

For each product you can see from which stage in the supply chain its emissions originate. This extends from land use changes on the left, through to transport and packaging on the right.

This is data from the largest meta-analysis of global food systems to date, published in Science by Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek (2018).

In this study, the authors looked at data across more than 38,000 commercial farms in 119 countries.2

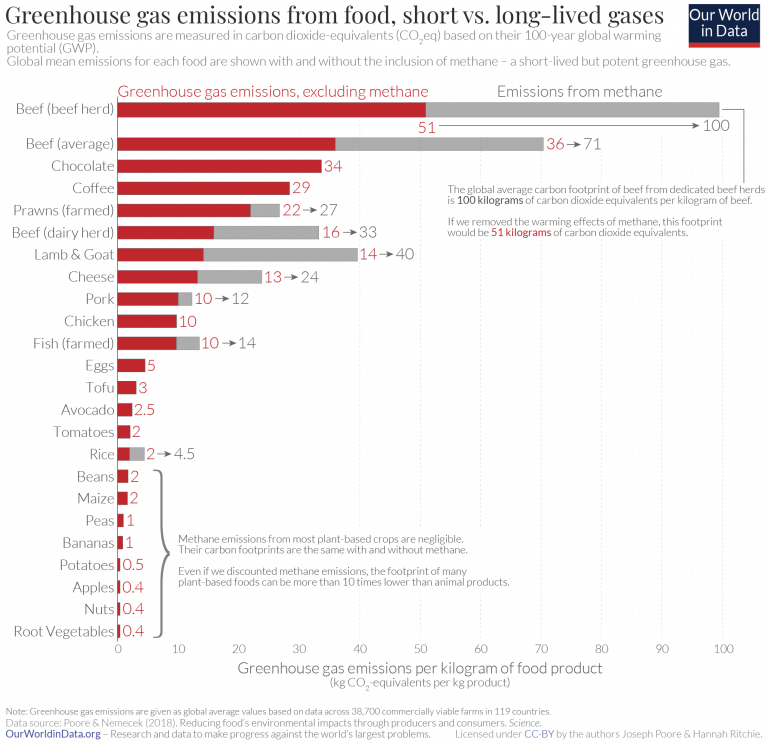

In this comparison we look at the total GHG emissions per kilogram of food product. CO2 is the most important GHG, but not the only one – agriculture is a large source of the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide. To capture all GHG emissions from food production researchers therefore express them in kilograms of ‘carbon dioxide equivalents’. This metric takes account not just CO2 but all greenhouse gases.3

The most important insight from this study: there are massive differences in the GHG emissions of different foods: producing a kilogram of beef emits 60 kilograms of greenhouse gases (CO2-equivalents). While peas emits just 1 kilogram per kg.

Overall, animal-based foods tend to have a higher footprint than plant-based. Lamb and cheese both emit more than 20 kilograms CO2-equivalents per kilogram. Poultry and pork have lower footprints but are still higher than most plant-based foods, at 6 and 7 kg CO2-equivalents, respectively.

For most foods – and particularly the largest emitters – most GHG emissions result from land use change (shown in green), and from processes at the farm stage (brown). Farm-stage emissions include processes such as the application of fertilizers – both organic (“manure management”) and synthetic; and enteric fermentation (the production of methane in the stomachs of cattle). Combined, land use and farm-stage emissions account for more than 80% of the footprint for most foods.

Transport is a small contributor to emissions. For most food products, it accounts for less than 10%, and it’s much smaller for the largest GHG emitters. In beef from beef herds, it’s 0.5%.

Not just transport, but all processes in the supply chain after the food left the farm – processing, transport, retail and packaging – mostly account for a small share of emissions.

This data shows that this is the case when we look at individual food products. But studies also shows that this holds true for actual diets; here we show the results of a study which looked at the footprint of diets across the EU. Food transport was responsible for only 6% of emissions, whilst dairy, meat and eggs accounted for 83%.4

Related content:

Eating local beef or lamb has many times the carbon footprint of most other foods. Whether they are grown locally or shipped from the other side of the world matters very little for total emissions.

Transport typically accounts for less than 1% of beef’s GHG emissions: choosing to eat local has very minimal effects on its total footprint. You might think this figure is strongly dependent on where in the world you live, and how far your beef will have to travel, but in the ‘dropdown box’ below I work through an example to show why it doesn’t make a lot of difference.

Whether you buy it from the farmer next door or from far away, it is not the location that makes the carbon footprint of your dinner large, but the fact that it is beef.

Example: how much does distance traveled impact the footprint of beef?

In a study published in Environmental Science & Technology, Christopher Weber and Scott Matthews (2008) investigated the relative climate impact of food miles and food choices in households in the US.5 Their analysis showed that substituting less than one day per week’s worth of calories from beef and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or a plant-based alternative reduces GHG emissions more than buying all your food from local sources.

By analysing consumer expenditure data, the researchers estimated that the average American household’s food emissions were around 8 tonnes of CO2eq per year. Food transport accounted for only 5% of this (0.4 tCO2eq).6 This means that if we were to take the case where we assume a household sources all of their food locally, the maximum reduction in their footprint would be 5%. This is an extreme example because in reality there would still be small transport emissions involved in transporting food from producers in your area.

They estimated that if the average household substituted their calories from red meat and dairy to chicken, fish or eggs just one day per week they would save 0.3 tCO2eq. If they replaced it with plant-based alternatives they would save 0.46 tCO2eq. In other words, going ‘red meat and dairy-free’ (not totally meat-free) one day per week would achieve the same as having a diet with zero food miles.

There are also a number of cases where eating locally might in fact increase emissions. In most countries, many foods can only be grown and harvested at certain times of the year. But consumers want them year-round. This gives us three options: import goods from countries where they are in-season; use energy-intensive production methods (such as greenhouses) to produce them year-round; or use refrigeration and other preservation methods to store them for several months. There are many examples of studies which show that importing often has a lower footprint.

Hospido et al. (2009) estimate that importing Spanish lettuce to the UK during winter months results in three to eight times lower emissions than producing it locally.7 The same applies for other foods: tomatoes produced in greenhouses in Sweden used 10 times as much energy as importing tomatoes from Southern Europe where they were in-season.8

The impact of transport is small for most products, but there is one exception: those which travel by air.

Many believe that air-freight is more common than it actually is. Very little food is air-freighted; it accounts for only 0.16% of food miles.9 But for the few products which are transported by air, the emissions can be very high: it emits 50 times more CO2eq than boat per tonne kilometer.10

Many of the foods people assume to come by air are actually transported by boat – avocados and almonds are prime examples. Shipping one kilogram of avocados from Mexico to the United Kingdom would generate 0.21kg CO2eq in transport emissions.11 This is only around 8% of avocados’ total footprint.12 Even when shipped at great distances, its emissions are much less than locally-produced animal products.

Which foods are air-freighted? How do we know which products to avoid?

They tend to be foods which are highly perishable. This means they need to be eaten soon after they’ve been harvested. In this case, transport by boat is too slow, leaving air travel as the only feasible option.

Some fruit and vegetables tend to fall into this category. Asparagus, green beans and berries are common air-freighted goods.

It is often hard for consumers to identify foods that have travelled by air because they’re rarely labeled as such. This makes them difficult to avoid. A general rule is to avoid foods that have a very short shelf-life and have traveled a long way (many labels have the country of ‘origin’ which helps with this). This is especially true for foods where there is a strong emphasis on ‘freshness’: for these products, transport speed is a priority.

So, if you want to reduce the carbon footprint of your diet, avoid air-freighted foods where you can. But beyond this, you can have a larger difference by focusing on what you eat, rather than ‘eating local’. Eating less meat and dairy, or switching from ruminant meat to chicken, pork, or plant-based alternatives will reduce your footprint by much more.