To make the transition to low-carbon energy sources and address climate change we need open data on the global energy system. High-quality data already exists; it is published by the International Energy Agency. But despite being an international institution that is largely publicly funded, most IEA data is locked behind paywalls. This makes it unusable in the public discourse and prevents many researchers from accessing it. Beyond this, it hinders data-sharing and collaboration; results in duplicated research efforts; makes the data unusable for the public discourse; and goes against the principles of transparency and reproducibility in scientific research. The high costs of the data excludes many from the global dialogue on energy and climate and thereby stands in the way of the IEA achieving its own mission.

We suggest that the countries that fund the IEA drop the requirement to place data behind paywalls and increase their funding – the benefits of opening this important data are much larger than the costs.

Transitioning to a low-carbon energy system is one of humanity’s most pressing challenges. Since 87% of annual carbon dioxide emissions come from the energy and industrial sectors, this transition is essential to address climate change.1 At the same time the provision of clean energy is also a priority for global health and human development: 10% do not have access to electricity; 41% do not have access to clean fuels for cooking, and estimates of the health burden of anthropogenic outdoor air pollution range from 4 to over 10 million premature deaths per year.

To understand the problems the world faces and see how we can make progress we need accessible, high-quality data. It needs to be global in scope – leaving no country absent from the conversation – and it needs to cover the range of metrics needed to understand the energy system: this includes primary energy, final energy, useful energy, the breakdown of the electricity mix, end-sector breakdowns of energy consumption, and the CO2 emissions that each sector produces.

This data exists. It is produced by the International Energy Agency (IEA). But the IEA only makes a fraction of their data publicly available, and keeps the rest behind very costly paywalls. This is despite the fact that the IEA is largely funded through public money from its member countries. The reason that the IEA puts much of its data behind paywalls is that the funders made it a requirement that it raises a small share of its budget through licensed data sales. As a consequence of this requirement the data is copyrighted under a strict data license; to access more than the very basic metrics, researchers and everyone else who wants to inform themselves about the global energy system needs to purchase a user license that often costs thousands of dollars.

In 2018, the annual budget of the IEA was EUR 27.8 million. According to the IEA’s budget figures, revenues from its data and publication sales finance “more than one-fifth of its annual budget”. That equates to EUR 5.6 million per year. To put this figure in perspective, it is equal to 0.03% of the total public energy RD&D budget for IEA countries in 2018, which was EUR 20.7 billion.2 Or on a per capita basis split equally across IEA member countries: 0.44 cents per person per year.3

We believe that the relatively small revenues that the paywalls generate do not justify the very large downsides that these restrictions cause.

Despite it being one of the most pressing challenges we face, energy is the only area of development without a global open-access dataset that researchers, policymakers and innovators can use to understand and tackle the problem. The paywalls the IEA is required to put in front of its data make it impossible for it to achieve its own mission. The IEA wants to be at the “heart of global dialogue on energy, providing authoritative analysis, data, policy recommendations, and real-world solutions to help countries provide secure and sustainable energy for all”, but as it stands the IEA is only providing data to rich elites as the restrictive licenses ensure that it cannot be part of the global dialogue on energy.

As explained, the problem is not so much the IEA itself, who surely has an interest in achieving its mission. The problem is the member countries’ imposition that the IEA has to raise a part of its budget through the sales of data licenses. To make it possible for the IEA to achieve its mission, the global energy and climate research community should therefore recommend to IEA member countries that they remove the requirement to charge for data use and close the relatively small funding gap that remains.

The pandemic has taught us many lessons over the past year. One key lesson has been that timely, accurate, and open global data is fundamental to the understanding of a global problem and an appropriate response to it. In the same way that the lack of public data would have stood in the way of fighting the pandemic, the lack of public data on the energy and climate system is standing in the way of solving one of the biggest challenges of our lifetime.

The IEA provides crucial energy data that is not available elsewhere

The statistical work of the IEA is of immense value. It is the only source of energy data that captures the full range of metrics needed to understand the global energy transition: from primary energy through to final energy use by sub-sector. It is the go-to source for most researchers and forms the basis of the energy systems modelling in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Reports.4 It is also heavily utilised in energy policy, collaborating with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) on developments in energy data and analytics.

Some alternative data sources on energy exist, but none come close to the coverage and depth of the IEA data. The BP Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the multinational oil and gas company BP is the most commonly used alternative. As a freely available dataset it is widely used in research and is where the IEA would want to be – ‘at the heart of the global dialogue on energy’. But as it is published by a private fossil fuel company it has some obvious drawbacks.

One is that it focuses on commercially-traded fuels; this means most high- and middle-income countries are included but lower-income countries are almost completely absent even from very basic metrics such as primary energy. It also focuses on primary energy statistics and does not offer insight into the breakdown in final energy or sector-specific allocations.

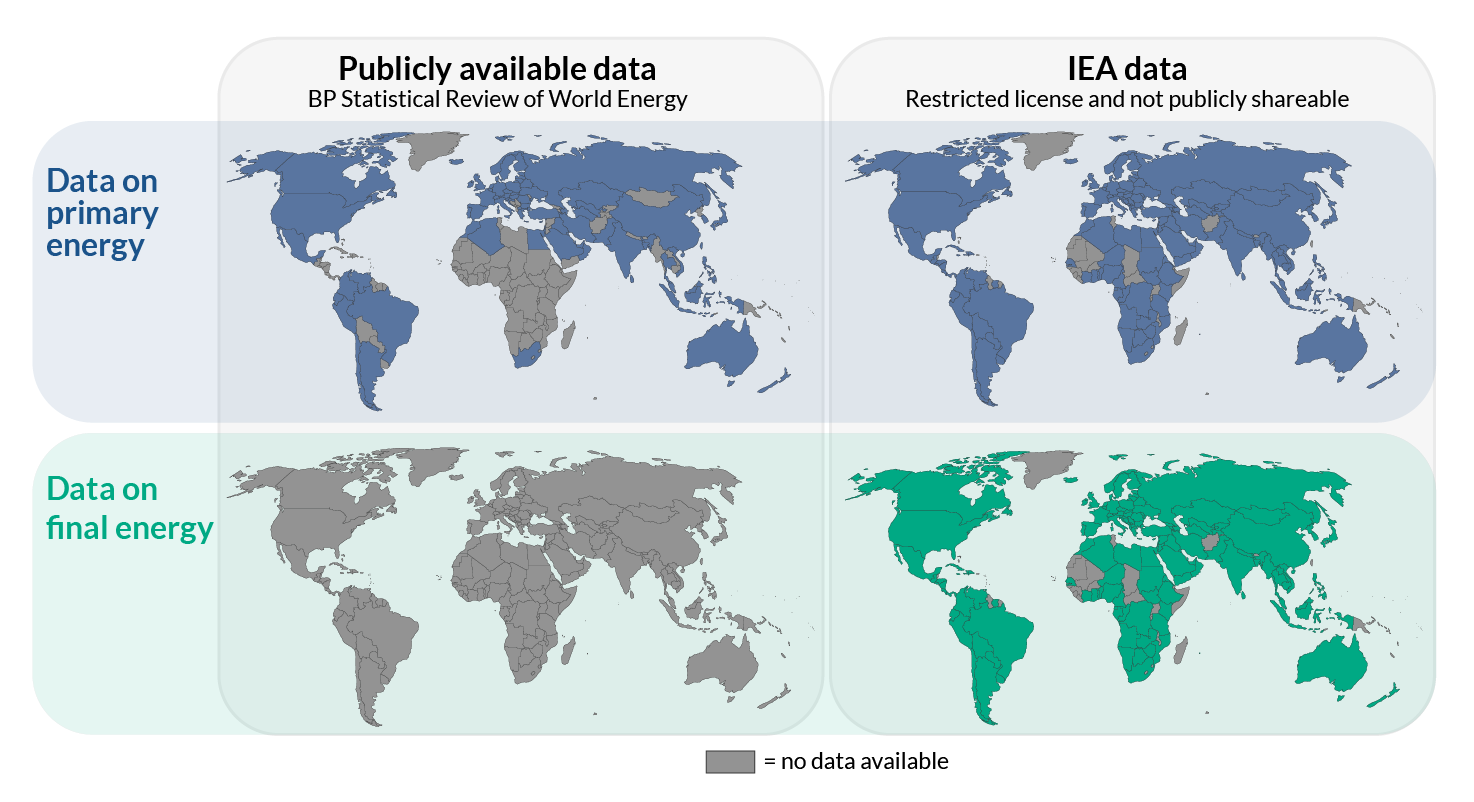

The series of maps show the comparative geographical coverage of primary and final energy between the publicly available dataset from BP, and the private licensed dataset from the IEA.

The breakdown of primary energy data to their final and end-use components is essential for understanding energy demand and future energy scenarios. Final energy demand is only one of many factors that determine primary energy consumption. Other important factors include the primary-to-secondary energy efficiency; final-to-useful energy efficiency; the sectoral structure of the economy; and the energy mix.5 The lack of publicly available data on final energy use is particularly problematic when it comes to understanding the transition to low-carbon energy sources and the evaluation of future energy demands.6 The gap between primary energy supply and final energy use is high for low-carbon energy sources and as the world adopts more of these energy sources the gap will increase. As an example: in the IEA and IRENA’s global energy transition scenarios for 2°C, final energy consumption in 2050 is typically 30% to 33% lower than primary energy supply.7

Final energy use is perhaps the most important energy statistic and should be at the center of the public discourse, but because no other institutions publish an international dataset on this metric, it is not. There are several other metrics of key importance for which only the IEA publishes internationally-comparable figures, including final energy use by energy source; allocation of energy to end-use sector; sector-specific energy use and CO₂ emissions (for example, no long-term time-series of aviation emissions exists in the public domain); CO₂ emissions from electricity; carbon intensity of electricity production; and power generation capacity by source to evaluate energy infrastructure timelines and potential stranded assets. There are also other important datasets – including Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) or the EMBER electricity dataset – but none of these sources include the same detail as the data published by the IEA.

Geographical coverage of the IEA’s data in comparison with an alternative dataset that is publicly available. Due to data restrictions on the IEA global energy dataset, the open-access BP dataset has become a default source. This energy data is only published for countries that primarily rely on commercially traded fuels, meaning most low-income countries are not included. It also does not include any information on final energy use, one of the most important metrics to understand the energy system.

Lack of open energy data hinders progress in science, technology and policy

The lack of open data hinders progress on the energy transition in several ways.

1. Duplicated efforts: since IEA data cannot be shared, researchers cannot share their analyses of IEA data, and their colleagues cannot build on their work. As a consequence, thousands of researchers and analysts across the world derive the same statistics independently from each other and many hours of work are spent on the same analyses.

2. Inequalities in data access and perspective: many perspectives are excluded from research and academic debate – many researchers, especially in poorer countries, cannot afford to buy the IEA data. Publicly available datasets on energy – such as BP – do not include low-income countries which means they are excluded from the conversation. As many of these countries make decisions about the future of their energy systems right now, it is vital that this data is available as soon as possible.

3. Credibility and replication challenges: since IEA data – and analyses built on top of this data – cannot be shared, verification is difficult and often impossible. Transparency and reproducibility are core principles in scientific research and neither the research that is based on IEA data nor the IEA itself (as every other group of researchers they also receive criticism for some aspects of their work) can adhere to this principle.

4. Outreach and engagement is difficult: the public needs to understand the problem of energy and climate change. The cost of accessing important data and the restrictions to use it in public however makes it difficult for journalists to do their work on these key global challenges.

It goes against the FAIR Guiding Principles – a set of principles agreed by stakeholders representing academia, industry, funding agencies, and scholarly publishers – for appropriate data management and stewardship in science.8 The licensing model of the IEA is in conflict with at least three of these basic principles: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable.

The current system has many downsides. Data restrictions make work more difficult for researchers – they duplicate efforts and cannot share their results freely. It means that policymakers often rely on research and commentary that is not based on the best data. It does not serve the IEA: it hinders its mission of leading the global dialogue on energy and means the immense value of its data and research team is under-utilized. Finally, it means the general public, journalists, innovators, or others interested in global energy and climate cannot properly engage in the conversation.

Because much of the research on energy and climate change is publicly funded, it is often also public money that pays for research to access IEA data; an absurd situation. The case for open energy data is not just a scientific and ethical one. There’s an obvious economic case for it. The status quo where research efforts are duplicated, time is wasted, and in which researchers and decision-makers rely on sub-optimal data creates large systemic inefficiencies. The economic cost of these inefficiencies likely dwarfs the small funding gap imposed on the IEA by the governments of its member countries.

Energy is one of the few development areas where data is private

The challenge of making international data publicly available is not a new one. The late statistician Hans Rosling previously diagnosed some of the large international organizations with chronic cases of DBHD or “Database Hugging Disorder”.

But while other institutions were cured of DBHD and have much improved the access to the data they produced, the energy and climate sector remains one of the few – if not the only – research area that lags far behind. To understand global food systems and nutrition the world can rely on the data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO); in global health we have the World Health Organization (WHO); in poverty and inequality we can rely on the data from the World Bank; in water and sanitation we have the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP). All of these institutions are largely publicly funded and all of them make their databases available as a public good, free and open-access for everyone. In this regard, energy is now the outlier among the world’s large global problems.

Many studies have illustrated the large social and economic benefits of public data. The World Bank – which previously had a similar data licensing model as the IEA – has now published a number of flagship reports highlighting the economic benefits of open data, and its critical role in sustainable development.9 One of its studies estimated that in the EU alone, open government data provided an economic value of 40 billion euros per year.10 The most widely-cited estimate of the economic value of open data globally – across both public and private sectors – comes from the McKinsey Global Institute: it estimated that open data across seven sectors could create 3 to 5 trillion dollars of economic value per year.11 Energy and transport were some of the most valuable sectors, with 340 to 580 billion dollars in electricity; 240 to 510 billion dollars in oil and gas; and 720 to 920 in transport. The funding that would make the IEA data publicly available is a very small fraction of these sums.

At the national level many countries have highlighted the value of open energy data too. For example, the UK government and energy regulator (Ofgem) commissioned an Energy Data Taskforce to investigate the role of data in decarbonizing the national grid.12 It found that open data-sharing was crucial to the energy transition: it facilitated improved understanding of balancing supply and demand; increased the efficiency of grid operations; reduced energy costs; and lowered the barrier of entry to innovators. The benefits we see at the national level should be transferable to understanding the global energy transition as a whole.

Faced with the urgent and global challenges of global energy access and climate change, accessing the basic data should not be this difficult. Making this data free and accessible for everyone is a very basic – but critical – first step. If we cannot even manage this, what are our chances of tackling the much bigger international problems facing us?

What can you do to help?

To fix this problem, the energy ministries that provide finance to the IEA need to change the restrictions on their funding contributions and close the small 5 to 6 million EUR gap.

You find the list of the 30 IEA member countries here. If you want to help move this discussion forward, you can contact your respective energy ministry and ask them to change it.