The media seems to have agreed that rich countries are experiencing a ‘loneliness epidemic’. There are literally thousands of newspaper articles that use this exact expression.

What is the evidence for this? The word ‘epidemic’ suggests that things are getting much worse and loneliness is increasing rapidly. But does the data in fact show that societies are becoming lonelier?

Despite the popularity of the claim, there is surprisingly no empirical support for the fact that loneliness is increasing, let alone spreading at epidemic rates.

It is true that more people are living alone around the world. But loneliness and aloneness are not the same. As we explain in a companion post, spending time alone is not a good predictor of whether people feel lonely, or have weaker social support.

As we explain later, today’s adolescents in the US do not seem to be more likely to report feeling lonely than adolescents from a couple of decades ago; and similarly, today’s older adults in the US do not report higher loneliness than older adults in the past. Surveys covering older adults in other rich countries, including Finland, Germany, England and Sweden, point in the same direction – it’s not the case that loneliness is increasing across generations in these countries.1

Social connections – including contact with friends and family – are important for our health and emotional welfare, as well as for our material well-being. Loneliness is indeed an important problem, but it’s crucial to have a nuanced conversation based on facts. The headlines that claim we are witnessing a ‘loneliness epidemic’ are wrong and unhelpful.

One statistic that is often used to argue that loneliness is increasing, is that young people today are lonelier than older adults. This begs two questions: (i) Is it true that younger people are lonelier, and (ii) does this show that loneliness is increasing?

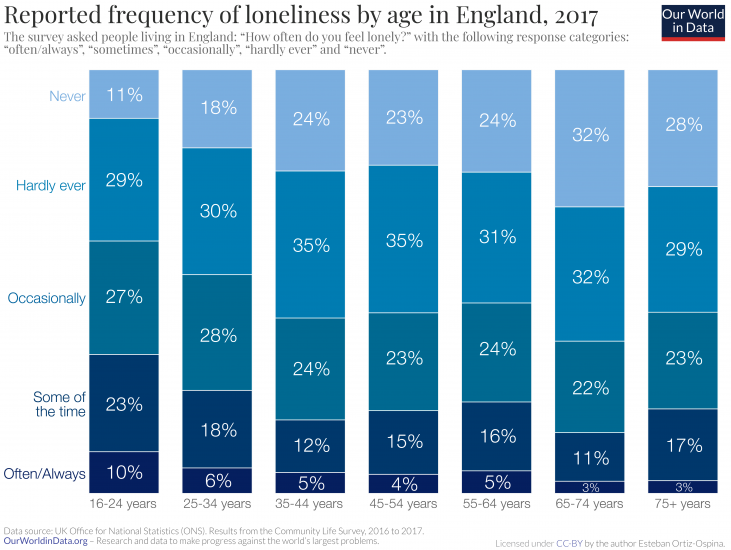

Let’s start with the first question. In England, the Office for National Statistics conducts the Community Life Survey, in which they ask people how often they feel lonely. In the bar chart here we show a breakdown of self-reported loneliness by age group.

According to this data, those aged 16 to 24 are the group most likely to report feeling lonely, with 10% feeling lonely “often or always”. In contrast, those aged 65 years and older are the group least likely to report feeling lonely, with 3% feeling lonely “often or always”.

Many people tend to associate loneliness with older age, so this pattern might seem surprising. But surveys from several other rich countries have found the same. In New Zealand, Japan and the US, young adults also report feeling lonely more often than older adults.

So, yes, in rich countries we find that younger people are more likely to report feeling lonely.2

What about the second question? Does this mean that loneliness is increasing?

Here, the answer is ‘no’. Cross-sectional comparisons are not informative about changes over time, because loneliness is not constant across the life cycle. To be able to say something meaningful about changes in loneliness over time, we need to distinguish between changes for individuals over time (do people become lonelier as they get older?) and changes across generations (are people of the same age lonelier today than in the past?).

Let’s dig deeper and explore these questions separately.

To understand how loneliness changes across our life cycle, we need loneliness data from surveys that track the same individuals over time, up until old age. In a study published in the journal Psychology and Aging, Louise Hawkley and co-authors examine two such surveys, with data for adults older than 50 years in the US.3

They found that after age 50 – which is the earliest age of participants in their study – loneliness tended to decrease, until about 75, after which it began to increase again.

The authors explain in their paper that the increase in loneliness after 75 was explained by a decline in health and the loss of a spouse or partner. When adjusting for these factors, they found that loneliness continued declining into ‘oldest old age’.

This shows that there are two forces at play. On the one hand, there seems to be a direct relationship between age and loneliness, whereby loneliness decreases with age as our social expectations adapt, and we become more selective about relating with contacts who bring positive emotions. On the other hand, there seems to be an indirect association pushing in the opposite direction, whereby loneliness increases with age, because our health deteriorates and we lose relatives and friends.

In our middle age the direct effect dominates, but once we enter advanced old age, the negative indirect effect starts dominating.

This complex relationship between age and loneliness shows why comparing old and young people at a given point in time is misleading. Cross-sectional comparisons are just not informative about the evolution of loneliness over time, because loneliness is not constant across the life cycle.

In the ‘loneliness epidemic’ narrative, it is often implied that if we compare two individuals of the same age – one today and another one a generation ago – we would find that the one today is more likely to feel lonely. This is based on the idea that there have been societal changes – such as the rise of living alone – that make newer generations more likely to feel lonely.

In their study, Louise Hawkley and co-authors searched for evidence of these ‘cohort trends’ in the US, but didn’t find any. There was very little difference in self-reported loneliness of people born in different generations. Those that were born in 1920-1947 experienced the same changes of loneliness throughout their lives as those born in 1948-1965. It’s not the case that loneliness is increasing across generations.

An article by Tom Chievers explains this result from the study very well: “[Hawkley and co-authors] found that “newer” old people (baby boomers born 1948-1965) are no more likely to think of themselves as lonely than “older” old people (born 1920-1947), and that older people have not become more likely to think of themselves as lonely in the last decade (2005 – 2016)… The average older person appears to be no more likely to be lonely than they were a decade ago.”

There are studies with data from other rich countries pointing in the same direction. In Sweden, repeated cross-sectional surveys with adults aged 85, 90, and 95 years old, found no increase in loneliness over a ten-year interval.4

These studies find no evidence of cohort effects across older adults. What about evidence for adolescents?

In the aptly titled paper “Rethinking ‘Generation Me’: A Study of Cohort Effects from 1976-2006”, the psychologists Kali Trzesniewski and Brent Donnellan used repeated cohort surveys to explore whether successive groups of high-school graduates were becoming more lonely in the US. They also found no evidence of cohort trends. Newer generations of high-school seniors were not more likely to report feelings of loneliness than earlier generations.5

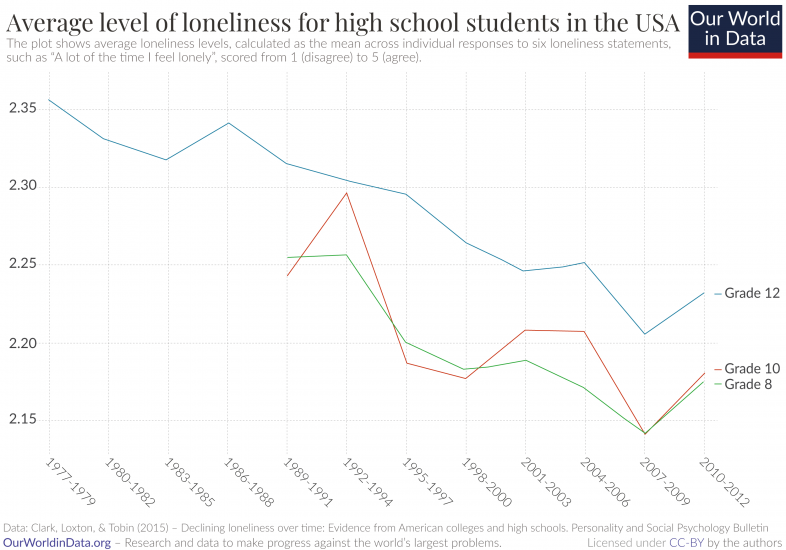

The psychologists Matthew Clark, Natalie Loxton, and Stephanie Tobin replicated this analysis, using the same survey, but focusing on all age groups, not only high-school seniors. The chart here shows their results. They found no signs of increasing loneliness across all age groups. In fact, they found a very small but statistically significant decline in loneliness for high school students in the US.6

(NB. The vertical axis in this chart is truncated, following the presentation in the original paper. The truncated axis is helpful to highlight the trend; but the takeaway is that the changes in levels are extremely small, so the trend is effectively flat in absolute terms, even if the slope is statistically different from zero).

The magazine The Economist wrote an article in 2018 with the title “Loneliness is a serious public-health problem”. In one key paragraph, the article reads: “Historical data about loneliness are scant. But isolation does seem to be increasing, so loneliness may be too.”

The data we have found shows that this reasoning is actually incorrect.

Surveys from rich countries do not suggest there has been an increase in loneliness over time. Today’s adolescents in the US do not seem to be more likely to report feeling lonely than adolescents from a couple of decades ago; and similarly, today’s older adults in the US do not report higher loneliness than did adults of their age in the past.

That’s of course not to say we should not pay attention to these topics.

It’s important to provide support to people who suffer from loneliness, just as it is important to pay attention to the policy challenges that come from large societal changes such as the rise of living alone. However, inaccurate, over-simplified narratives are unhelpful to really understand these complex challenges.

There is an epidemic of headlines that claim we are experiencing a “loneliness epidemic”, but there is no empirical support for the fact that loneliness is increasing, let alone spreading at epidemic rates.