- Several surveys show that frequent users of social media tend to have problems with anxiety, depression and sleep problems. Newspapers often interpret this correlation causally, and paint a scary picture in which social media is to blame for large and persistent mental health problems.

- If you dig deeper, you find that comparisons across individuals with different levels of social media use can yield conflicting results – depending on how you slice the data you get a different perspective.

- Surveys that track individuals over time suggest that the relationship is reciprocal (depression and social media use go hand in hand), and social media use only predicts a small change in well-being over time.

- Large and credible experimental studies have found that quitting facebook has a positive but small short-run causal impact on well-being, detectable only on some specific outcome measures.

- Overall, the evidence does not support the sweeping newspaper headlines. There is much to be learned about how to make better use of these complex digital platforms, but for this we need more granular data to unpack the different effects that certain types of content have on specific population groups.

Facebook, Youtube, Whatsapp, WeChat, and Instagram are the top five social media platforms globally, with over one billion active users each. In most rich countries the proportion of young people using online social networks exceeds 90% and teens spend on average more than 4 hours online every day.

We’re repeatedly told in the news that social media is bad for us. The stories are often alarming, suggesting social media and smartphones are responsible for sweeping negative trends, from rising suicide rates in the US, to widespread loss in memory, and reduced sleep and attention spans.

These worrying headlines often go together with implicit or explicit recommendations to limit the amount of time we spend on social media. Indeed, smartphones today come with built-in “screen time” apps that let us track and limit how much time we spend online.

At the same time, most of us would agree that digital social media platforms can make our lives easier in many ways – opening doors to new information, connecting us with people who are far away, and helping us to be more flexible with work.

What does the research tell us about the causal impact of social media use on our well-being?

In a nutshell: From my reading of the scientific literature, I do not believe that the available evidence today supports the sweeping newspaper headlines.

Yes, there is evidence suggesting a causal negative effect, but the size of these causal effects is heterogeneous and much, much smaller than the news headlines suggest.

There are still plenty of good reasons to reflect on the impact of social media in society, and there is much we can all learn to make better use of these complex digital platforms. But this requires going beyond universal claims.

Let’s take a look at the evidence.

Most of the news stories that claim social media has a negative impact on well-being rely on data from surveys comparing individuals with different levels of social media use as evidence. In the chart below, I show one concrete example of this type of correlational analysis.

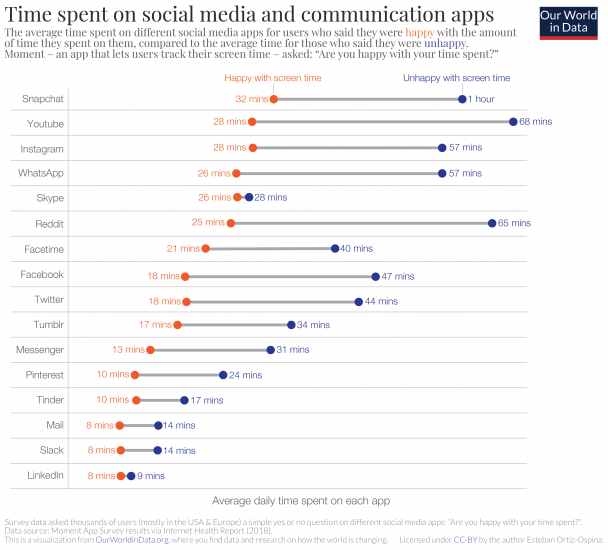

The chart plots the average amount of time that people spend on social media each day, among people who are and aren’t happy with the amount of time spent on these platforms.

The data comes from an app called Moment, which tracks the amount of time users spend on social media platforms on their smartphones. The app also asks people a yes/no question: “Are you happy with your time spent?”

As we can see there is quite a bit of heterogeneity across platforms, but the pattern is clear: People who say they are happy with how much time they spend on social media spend less time on these platforms. Or put differently, using social media more heavily is correlated with less satisfaction.

This is certainly interesting, but we should be careful not to jump to conclusions – the correlation actually raises as many questions as it answers.1

Does this pattern hold if we control for user characteristics like age and gender? Would we get similar results if we focused on other measures of well-being beyond ‘happy with time spent’?

The answer to both questions is ‘no’. Depending on what outcome variables you focus on, and depending on which demographic characteristics you account for, you will get a different result. It is therefore not surprising that some empirical academic studies have found negative correlations; while others actually report positive correlations.2

Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski published a paper earlier this year in the journal Nature where they illustrated that given the flexibility to analyze the data (i.e. given the number of possible choices researchers have when it comes to processing and interpreting the vast data from these large surveys), scientists could have written thousands of papers describing positive, negative and non-significant associations. Different ways of measuring well-being and social media use will yield different results, even for the same population.3

Even the answers to some of the most fundamental questions are unclear: Do we actually know in which direction the relationship might be going? Does frequent social media use translate into lower happiness, or is it the other way around – are anxious, stressed or depressed people particularly prone to use social media?

This takes us to another branch of the literature: longitudinal studies that track individuals over time to measure changes in social media use and well-being.

One longitudinal study that has received much attention on this subject was published by Holly Shakya and Nicholas Christakis in the American Journal of Epidemiology in 2017. It used data from a survey that tracked a group of 5,208 Americans over the period 2013 – 2015, and found an increase in Facebook activity was associated with a future decrease in reported mental health.4

Two years later, Amy Orben, Tobias Dienlin and Andrew Przybylski published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences using a similar source of data. They relied on a longitudinal survey from the UK covering 12,672 teenagers over the period 2009 – 2016, and reached a different conclusion. They found that there was a small and reciprocal relationship: social media use predicted small decreases in life satisfaction; but it was also the case that decreasing life satisfaction predicted subsequent increases in social media use.5

Summarizing their research in The Guardian, Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski explained: “we did find some small trends over time – these were mostly clustered in data provided by teenage girls… But – and this is key – it’s not an exaggeration to say that these effects were minuscule by the standards of science and trivial if you want to inform personal parenting decisions. Our results indicated that 99.6% of the variability in adolescent girls’ satisfaction with life had nothing to do with how much they used social media.”

In their paper Orben and co-authors argue again that these large datasets allow many different types of empirical tests; so it is natural to expect conflicting results across studies, particularly if there is noise in measurement and the true effect sizes are small.6

Orben and co-authors tested thousands of empirical tests and indeed, some of these tests could have been interpreted on their own as evidence of a strong negative effect for social media – but clearly the broader picture is important. When looking at the results from all their thousands of tests, they concluded that social media effects were nuanced, small at best and reciprocal over time.7

Establishing causal impacts through observational studies that track the well-being of individuals over time is difficult.

First, there are measurement issues. Long-run surveys that track people are expensive and impose a high burden on participants, so they do not allow in-depth high-frequency data collection, and instead focus on broad trends across a wide range of topics. Orben and co-authors, for example, rely on the Understanding Society Survey from the UK, which covers a wide range of themes such as family life, education, employment, finance, health and wellbeing. Specifically on social media use, this survey only ask how many hours teenagers remember using apps during normal weekdays, which is of course an informative but noisy measure of actual use (a fact that Orben and co-authors mention in their paper).

Second, there are limitations from unobservable variables. Frequent users of social media are likely different from less frequent users in ways that are hard to measure – no matter how many questions you include in a survey, there will always be relevant factors you cannot account for in the analysis.

Given these limitations, an obvious alternative is to run an experiment: you can, for example, offer people money to stop using Facebook for a while and then check the effect by comparing these “treated participants” against a control group that is allowed to continue using Facebook as usual.8

Several recent papers followed this approach. Here I’ll discuss one of them in particular, because I find its approach particularly compelling. The analysis relies on a much larger sample than other experiments, and the researchers registered a pre-analysis plan to insure themselves against the ‘analytical flexibility’ criticisms discussed above.9

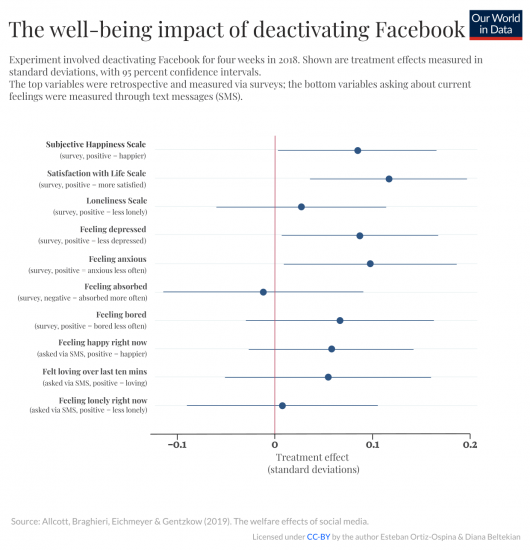

This experiment was done by four economists: Hunt Allcott, Sarah Eichmeyer, Luca Braghieri and Matthew Gentzkow. They recruited 2753 Facebook users in the US, and randomly selected half of them to stop using Facebook for four weeks. They found that deactivating Facebook led to small but statistically significant improvements in some measures of self-reported well-being.10

The chart below shows a summary of their estimated effect sizes. As we can see, for all measures the effects are small (amounting to only around a tenth of the standard deviation of the studied variable), and in most cases the effects are actually not statistically significant (the ‘whiskers’ denoting 95% confidence intervals often include an effect of size zero).11

Allcott and co-authors also compare the treatment effects against the observational correlations in their sample and conclude: “the magnitudes of our causal effects are far smaller than those we would have estimated using the correlational approach of much prior literature”.12

The relatively small experimental effect of social media use on subjective well-being has been replicated. Another experiment conducted almost at the same time and with a very similar approach, produced similar results.13

In the US, where many of these studies have been conducted, roughly two-thirds of people get news from social media, and these platforms have already become a more widely accessed source of news than print newspapers.

I think this link between social media, news consumption and well-being is key.

In their experiment, Allcott and coauthors found that quitting Facebook did not lead people to use alternative online or offline news sources; so those in the treatment group reported spending less time consuming news overall. This tells us that the effect of social media on well-being is not only relatively small, but also likely mediated by the specific types of content and information that people are exposed to.14

The fact that news consumption via social media might be an important factor affecting well-being is not surprising if we consider that news are typically biased towards negative content, and there is empirical research suggesting people are triggered, at a physiological level, when exposed to negative news content.15

Building and reinforcing a scary overarching narrative around “the terrible negative effects of social media on well-being” is unhelpful because this fails to recognise that social media is a large and evolving ecosystem where billions of people interact and consume information in many different ways.

The first takeaway is that the association between social media and well-being is complex and reciprocal, which means that simple correlations can be misleading. A careful analysis of survey data reveals that, yes, there is a correlation between social media and well-being; but the relationship works both ways. This becomes clear from the longitudinal studies: Higher use of social media predicts decreases in life satisfaction; and decreasing life satisfaction also predicts subsequent increases in social media use.

The second takeaway is that the causal effect of social media on well-being is likely small for the average person. The best empirical evidence suggests the impact is much smaller than many news stories suggest and most people believe.

There is much to be learned about how to make better use of these digital platforms, and there is an important discussion to be had about the opportunity costs of spending a large fraction of our time online. But for this we need to look beyond the sweeping newspaper headlines.

We need research with more granular data to unpack diverse use patterns, to understand the different effects that certain types of content have on specific population groups. Time alone is a poor metric to gauge effects. As Andrew Przybylski put it: nobody would argue we should study the causes of obesity by investigating ‘food time’.

Going forward, the conversation in policy and the news should be much more about strategies to promote positive content and interactions, than about one-size-fits-all restrictions on social media ‘screen time’.