How different would your life be if you never went to school and never learned how to read and write?

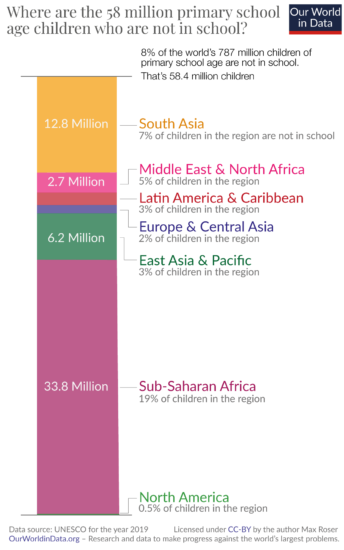

Of the world’s 787 million children of primary school age 8% do not go to school.1 That’s 58.4 million children. The chart shows where they live in the world.

This is UNESCO data for the year 2019. During the pandemic this number increased temporarily, but even at pre-pandemic levels – to which the world will hopefully return soon – the number was much too high. 58 million children out of primary school means 58 million who don’t even have the chance to learn how to read and write.

To make progress we have to understand why children are not in school.

One major reason is violence in the world’s ongoing conflict areas, including Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Nigeria. Half of all out-of-school children live in conflict-affected countries.3

The other large barrier – often closely intertwined with conflict – is poverty.4

In low-income countries public finances for education are very low: the annual spending in a high-income country like Austria is more than 200-times higher per student than in a low-income country like the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the worst cases poverty requires children to work – most commonly on smallholder farms – and this means they leave school early or never enter school in the first place.

If we want to make progress on education then we will need to continue the developments that reduce conflict and poverty.

These macro changes are essential, but can seem intangible in the short-term. Targeted policies can make a difference in such situations. One policy with a long and well-established track record is to provide free meals in schools. School meals achieve two goals at the same time: They are offering children a better diet, and they provide an incentive for parents to send their children to school. Research studies have shown that school meals increase school attendance and have a long-lasting impact over the child’s lifetime. A study in Sweden showed that pupils who received meals in school in the 1960s had 3% higher lifetime incomes.5 They have even been shown to have intergenerational benefits: the children of mothers who received school meals when they were children also benefit from school meal programs.6

As is so often the case with large global problems, the state of the world today is at the same time terrible, yet also much better than it was in the past.

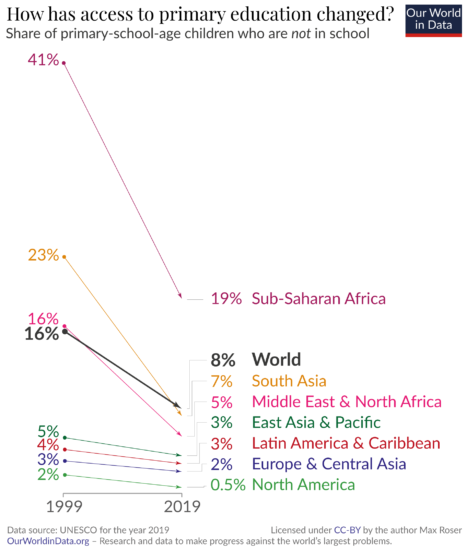

This chart here shows the same data as the first one, but it now also shows how the world has changed since the previous generation, 20 years ago. The share of children who are out-of-school has declined in all world regions. Globally, this share has halved. Today, 8% of children are not in school; twenty years ago this was 16%.

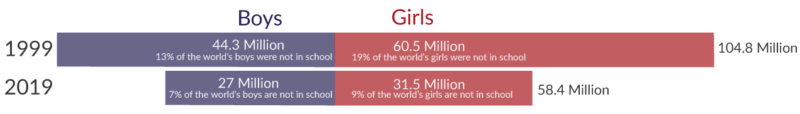

A generation ago it was girls in particular who did not have access to schools. This inequality has declined and today the absolute number and the share of boys and girls who are out of primary school is similar.8

This recent change is part of a much larger development that spans the last few generations.

Until then, no matter where a child was born its chances of getting even the most basic education were very small. Everywhere in the world education was restricted to a small elite population.9

The chart shows this big global development. In all countries – including those where children today have the best education – widespread access to even basic education is a recent achievement.10

Reading is the single most important educational skill a young child can learn. How did literacy change as more and more children gained access to a basic education?

The chart shows that two centuries ago only 1 out of every 10 adults knew how to read and write. This ratio has flipped since then: today about 9 in 10 adults do have this basic skill.

To make progress against the world’s problems we need a strong team of educated people. From this perspective it makes sense to consider this global change in absolute numbers. Today there are about 4.6 billion people who can read and write.11 In 1800 there were fewer than 100 million people with the same skill. We have a much stronger team than ever before.

The majority of children that have ever lived did not have the opportunity to fulfill their potential. In the extreme poverty of the pre-growth economies, children with great potential ended up living a life in poverty. Even very basic educational skills – like reading and writing – were a privilege of a small elite.

It is hard to imagine what all these girls and boys could have become. Perhaps it is easier to see the importance of at least basic education by looking at those around us today, and ask what their chances would have been without it. What would have become of Marie Curie, Jane Austen, Steve Jobs, Grace Hopper, or Einstein if they were born into a society in which children didn’t have access to basic education?

The world has made a lot of progress in recent generations, but a lot of work is left for our generation today. Almost 60 million children are growing up without the opportunities that you and I had thanks to the primary school that we were able to attend.

In this text I focused on access to primary education. In my next post I will focus on the quality of education. I will show how extremely large the differences in educational quality between countries are and which opportunities there are to improve education, especially for the very poorest children in the world.

If you want to read this post you can sign up for our Our World in Data newsletter.

Continue reading on Our World in Data now: