Smoking is so common, and feels so familiar, that it can be hard to grasp just how large the impact is. Every year, around 8 million people die prematurely as a result of smoking.1 This means that about one in seven deaths worldwide are due to smoking.2 Millions more live in poor health because of it.

Smoking primarily contributes to early deaths through heart diseases and cancers. Globally, more than one in five cancer deaths are attributed to smoking.

This means tobacco kills more people every day than terrorism kills in a year.3

Smoking is a particularly large problem in high-income countries. There, cigarette smoking is the most important cause of preventable disease and death.4 This is especially true for men: they account for almost three-quarters of deaths from smoking.5

The impact of smoking is devastating on the individual level. In case you need some motivation to stop smoking: The life expectancy of those who smoke regularly is about 10 years lower than that of non-smokers.6

It’s also devastating on the aggregate level. In the past 30 years more than 200 million have died from smoking.7 Looking into the future, epidemiologists Prabhat Jha and Richard Peto estimate that “If current smoking patterns persist, tobacco will kill about 1 billion people this century.”8

It is on us to prevent this.

How to make progress against the millions of deaths from smoking?

The most fundamental work to prevent millions of deaths is already done. We know that smoking kills.

This fact is so widely known today that it is hard to imagine that until the middle of the last century nobody was aware of it.9

People who do not think well about the work of statisticians sometimes fall for the idea that statistics are incapable of seeing and understanding the reality that is right in front of our eyes. The impact of smoking is a clear example where the opposite is true – for many decades smokers themselves were entirely blind to the fact that their habit was poisoning and eventually killing them. I have an old mountaineering guide that gives climbers the advice that they should take a pause every now and then during the climb so that they can smoke a cigarette as it “opens up the lungs.” The reality that smoking causes cancer and heart disease became only visible through careful statistical analysis.

Many of the most important facts are not even visible to those who are impacted by them. Often you need statistics to see what your world actually looks like.10

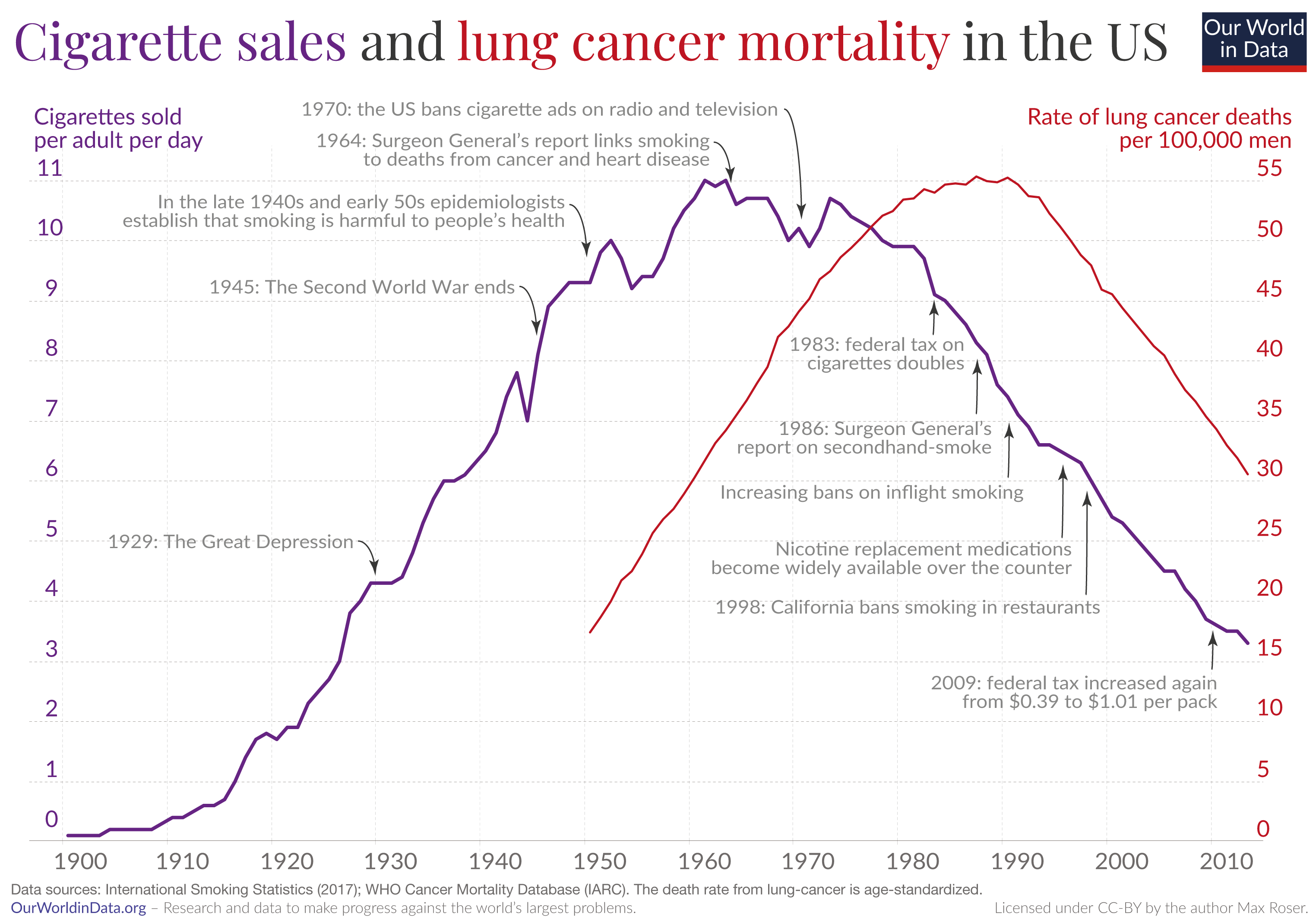

The chart summarizes the history of smoking in the US (the development in other high-income countries was similar). I plotted two different metrics: in purple you see the rise and fall of cigarette sales, which you can read off the values on the left-hand axis. In red you see the rise and fall of lung cancer deaths, which you can read off the axis on the right.

Smoking was very much a 20th century problem. It was rare at the beginning of the century, but then – decade after decade – it became steadily more common. By the 1960s it was extremely widespread: on average, American adults were buying more than 10 cigarettes every day.

The statistical work that identified smoking as the major cause of the rise in lung cancer deaths began in the post-war periods and culminated in the 1964 report of the Surgeon General. This report is seen as a turning point in the history of smoking as it made clear to the public just how deadly it was.11

Once people learned that smoking kills, they could act on it. It took some time, but they did.

I wasn’t alive during peak-smoking, but even I remember how very common it was to smoke in places where it would be unthinkable today. Looking back I also remember how surprised I was by how quickly smoking then declined. It is a good reminder of how wrong it often is to think that things cannot be different – for a long time smoking kept on increasing and it looked as if it would never change. But then it did.

Nearly half of all former smokers have quit,12 cigarette sales declined to a third of what they once were, and the death rate from lung cancer declined.

For some time it looked as if people in poorer countries followed the path of people in richer countries. As they became richer they started to smoke more.

But more recently this has changed, as the line chart shows: the share of people who smoke is declining in rich and poorer countries.

The fact that poorer countries are not following the stupidity of the early industrializers is a very positive development. This is good news for global health, as we see in the scatterplot. In most countries in the world – all the countries above the grey line – the death rate from smoking is now lower than back in 1990.

The decline of smoking is achieved through a successful global health campaign.13 A number of factors mattered – all of them clear reminders that good public policy can oppose the interests of big business when it really matters:

By taxing cigarettes very heavily, many governments made cigarettes much more expensive. Reducing the affordability of cigarettes is one of the most important – and cost-effective ways – to reduce smoking and increase public health.

Tobacco advertisement – once omnipresent – was restricted or banned in many countries.

Many countries also offered smokers support to help them quit smoking.

Smoking was also banned in public places where it was once common – in restaurants, bars, planes, and talk-shows.

One argument for government intervention is the fact that a large number of people die from smoking who are not smokers themselves. About 1.2 million people die every year from passive secondhand-smoke: exposure from the smoke of others.14

The various health campaigns reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle: once smoking becomes less common the peer pressure to smoke disappears. Instead, the pressure from peers turns against cigarettes and it becomes an increasingly unpopular thing to do.

The argument in favour of smoking is that many people enjoy it; that is, of course, an important argument. But you should be clear to yourself that you have to enjoy it a lot to justify it. About two-thirds of those who were still smokers when they died, died because of their smoking.15

Even decades after we learned that smoking kills it is hard to understand just how damaging smoking really is. Imagine how we would think of an extreme sport in which two-thirds of those who practice it die. If you are fascinated by the risk-taking of climbers like Reinhold Messner or Alex Honnold, that’s nothing compared to what smokers are willing to do.

The devastation caused by smoking today is still terrible. On any average day it kills more than 20,000 people.16

It will remain one of the largest health problems in the world for many years to come. Even after a long decline, about one-in-five adults in the world smokes, and, as we’ve seen above, it takes decades for a reduction in smoking to translate into a reduction of the death rate.

It is difficult to overcome an addiction, but the benefits from stopping are huge. Studies show that those who stop smoking in the first four or five decades of their life do not suffer from elevated mortality risks.17 But the benefits from smoking cessation are large at any age.

We can win the fight against smoking. Among the largest problems in the world it is one where I feel most certain that we can achieve a lot of progress. Thanks to the statisticians we have the scientific knowledge to know about its consequences; we know that the public health campaigns work; and we can appeal to peoples’ self-interest to not shorten their lifespan by 10 years.

Or more positively, we can appeal to peoples’ self-interest to live 10 more years of their life!

The share of the world population that is following this crippling path is falling. The world is breaking patterns of the past. If we continue making progress we will not have to see a billion smokers die an early death this century.