Summary

Many researchers have independently studied mortality rates for children in the past: in different societies, locations, and historical periods. The average across a large number of historical studies suggests that in the past around one-quarter of infants died in their first year of life and around half of all children died before they reached the end of puberty.

Since then the risk of death for children has fallen around the world. The global average today is 10 times lower than the average of the past. In countries with the best child health today an infant is 170 times more likely to survive.

Largely unseen and rarely reported, the deaths of children are a daily tragedy of immense scale. Globally 4.6% of all children die before they are 15 years old; on average a child dies every 5 seconds today.1

What was the mortality rate in the past? Anthony Volk and Jeremy Atkinson2 set out to answer this question. They brought together quantitative estimates on mortality at a young age from a wide range of geographic locations and cultures, going back many centuries.

The authors report mortality rates relative to two different age cut-offs:

– The infant mortality rate measures the share who died in their first year of life.

– The youth mortality rate measures the share who died before reaching “approximate sexual maturity at age 15”.3

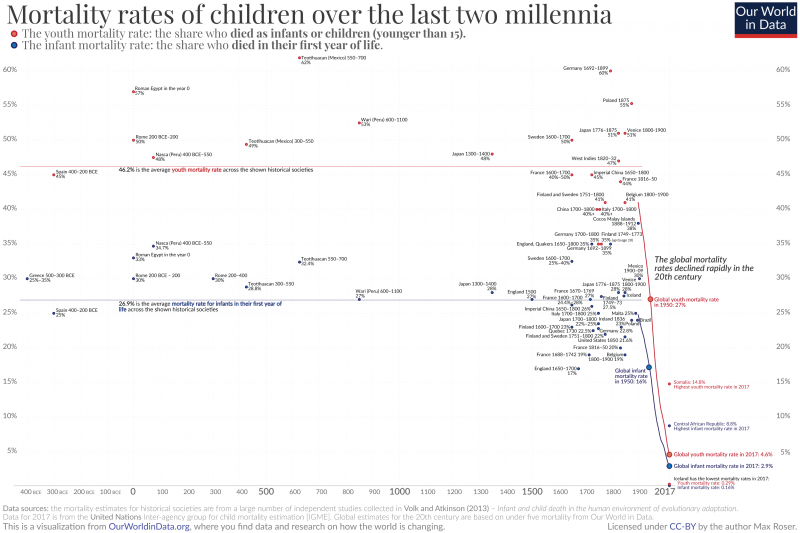

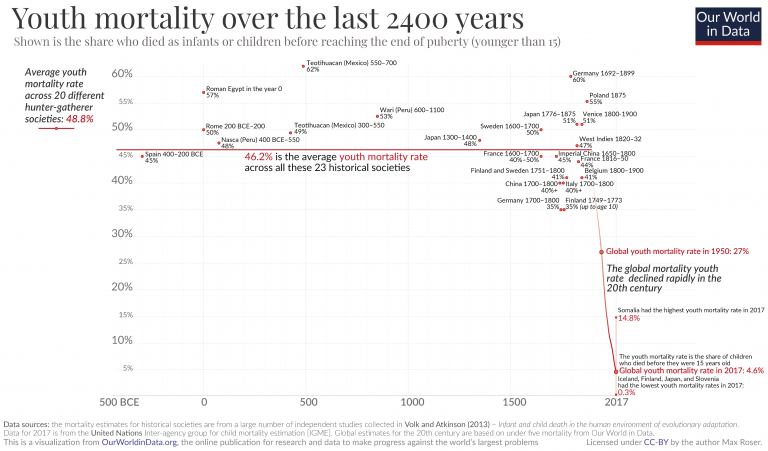

This visualization shows the historical estimates Volk and Atkinson brought together from a large number of different studies. Shown with the blue marks are estimates of the share of newborns that died in the first year of life – the infant mortality rate. And shown with the red marks you see different estimates of the share that never reached adulthood – what we here refer to as the ‘youth mortality rate’.

Across the entire historical sample the authors found that on average, 26.9% of newborns died in their first year of life and 46.2% died before they reached adulthood. Two estimates that are easy to remember: Around a quarter died in the first year of life. Around half died as children.

What is striking about the historical estimates is how similar the mortality rates for children were across this very wide range of 43 historical cultures. Whether in Ancient Rome; Ancient Greece; the pre-Columbian Americas; Medieval Japan or Medieval England; the European Renaissance; or Imperial China: Every fourth newborn died in the first year of life. One out of two died in childhood.

The available evidence for the mortality rates of children in hunter-gatherer societies and also for our closest relatives – Neanderthals and primates – I summarize at the end of this post.

On the very right of the chart you see the statistics on child health in the world today: The global infant mortality rate is now 2.9%. And 4.6% die before reaching the age of 15.

The global mortality rates over the course of the 20th century are also shown in the chart. Just as recently as 1950 the global mortality rates were five times higher. We have seen a very steep decline during our lifetimes.

The chances of survival for a newborn today are around 10-times higher than the past. But in some countries mortality rates are still much higher than the world average. The country with the highest infant mortality rate is the Central African Republic where close to 9% of all infants die.

The country with the lowest infant mortality rate today is Iceland at 0.16%. The chances of an infant surviving there are 170-times higher than in the past.

Even on the basis of many dozen studies we only have some snapshots of the long history of our species. Could they all mislead us to believe that mortality rates were higher than they actually were?

There is another piece of evidence to consider that suggests the mortality of children was in fact very high in much of humanity’s history: birth rates were high, but population growth was close to zero.

The fertility rate was commonly higher than 6 children per woman on average, as we discuss here. A fertility rate of 4 children per woman would imply a doubling of the population size each generation; a rate of 6 children per woman would imply a tripling from one generation to the next. But instead population barely increased: From 10,000 BCE to 1700 the world population grew by only 0.04% annually. A high number of births without a rapid increase of the population can only be explained by one sad reality: a high share of children died before they could have had children themselves.

Volk and Atkinson also explain that their historical mortality rates “should be viewed as conservative estimates that generally err toward underestimating actual historic rates”. A first reason is that death records were often not produced for children, especially if children died soon after birth. A second reason they cite is that child burial remains, another important source, are often incomplete “due to the more rapid decay of children’s smaller physical remains and the lower frequency of elaborate infant burials”.4

And lastly, we find that a large number of independent studies for very different societies, locations, and times come to surprisingly similar assessments: all point to very high mortality rates for children. For societies that lived thousands of kilometers away from each other and were separated by thousands of years of history, mortality in childhood was terribly high in all of them. The researchers find that on average a quarter of infants died before their first birthday and half of all children died before they reached puberty.

How does the historical data compare with the world today? Globally 95.4% of all children survive the first 15 years of life.

This is a dramatic change from the past. As we’ve seen above: The research suggests that in our long history the chances for a child to survive were about fifty-fifty.

The map shows the mortality up to the age of 15 in every country today. By clicking on any country in this map you see the change over time. You will find that the mortality rate declined in every country around the world.

But you also see that in some parts of the world, youth mortality is still very common. Somalia – on the Horn of Africa – is the country with the highest rate at 14.8%.

And the map also shows the regions with the best health. In the richest parts of the world deaths of children became very rare. In Iceland, the country with the lowest youth mortality, the chances a child survives their first 15 years of life are 99.71%.

The second metric we studied above was the infant mortality rate in the first year of life. Across the historical societies this rate was around a quarter; the global rate today is 2.9%. In our map for infant mortality you find the data for every country in the the world.

Today’s mortality rates of children are still unacceptably high, but the progress that humanity has achieved is substantial. Our ancestors could have surely not imagined what is reality today. And for me this progress is one of the greatest achievements of humanity.

Additional information

Mortality at young ages in hunter gatherer societies

The historical record the authors investigated goes back 2500 years. What about prehistory when our ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers?

Good evidence here is much harder to come by. To study mortality at a young age in prehistoric societies the researchers need to mostly rely on evidence from modern hunter-gatherers. Here, one needs to be cautious of how reflective modern societies are of the past. This is because recent hunter-gatherers might have been in exchange with surrounding societies and “often currently live in marginalized territories”, as the authors say. Both of these could matter for mortality levels.

To account for this, Volk and Atkinson have attempted to only include hunter-gatherers that are best representative for the living conditions in the past; they limited their sample “only to those populations that had not been significantly influenced by contact with modern resources that could directly influence mortality rates, such as education, food, medicine, birth control, and/or sanitation.”

Again, the researchers find very similar mortality rates across their sample of 20 different studies on hunter-gatherer societies from very different locations: The average infant mortality rate (younger than 1) was 26.8% and the average mortality before puberty, 48.8%. Almost exactly the same as the historical sample discussed above.

All but one of these studied societies are modern hunter-gatherers. The one study on mortality rates of paleolithic hunter-gatherers investigates the famous Indian Knoll archaeological site from around 2,500 BCE, located in today’s area of Kentucky.5

For this community the estimates suggest that mortality at a young age was even higher than the average for modern-day hunter-gatherers: 30% died in their first year of life, and 56% did not survive to puberty.

Neanderthals and primates – the mortality of our closest relatives

Going beyond our own species (homo sapiens), researchers have also attempted to measure the mortality rates at young ages for our closest relatives.

Studies that focussed on the Neanderthals, our very closest relatives who lived within Eurasia from circa 400,000 until 40,000 years ago, suggest that they suffered infant mortality rates similar to our species before modernization: it is estimated that around 28% died in the first year of life.6

Atkinson and Volk also compared human child mortality rates across species with other primates. Bringing together many different sources the authors find the mortality rates of young chimpanzees and gorillas to be similar to the mortality rates of humans of the past, while other primates differ: orangutans and bonobos appear to have somewhat lower mortality rates and baboons, macaques, colobus monkeys, vervet monkeys, lemurs and other primates suffer from higher mortality rates.