The average person in the world is 4.4-times richer than in 1950. But beyond this global average, how did incomes change in countries around the world? Who gained the most, who gained the least? And why should we care about the growth of incomes? These are the questions I answer in this post.

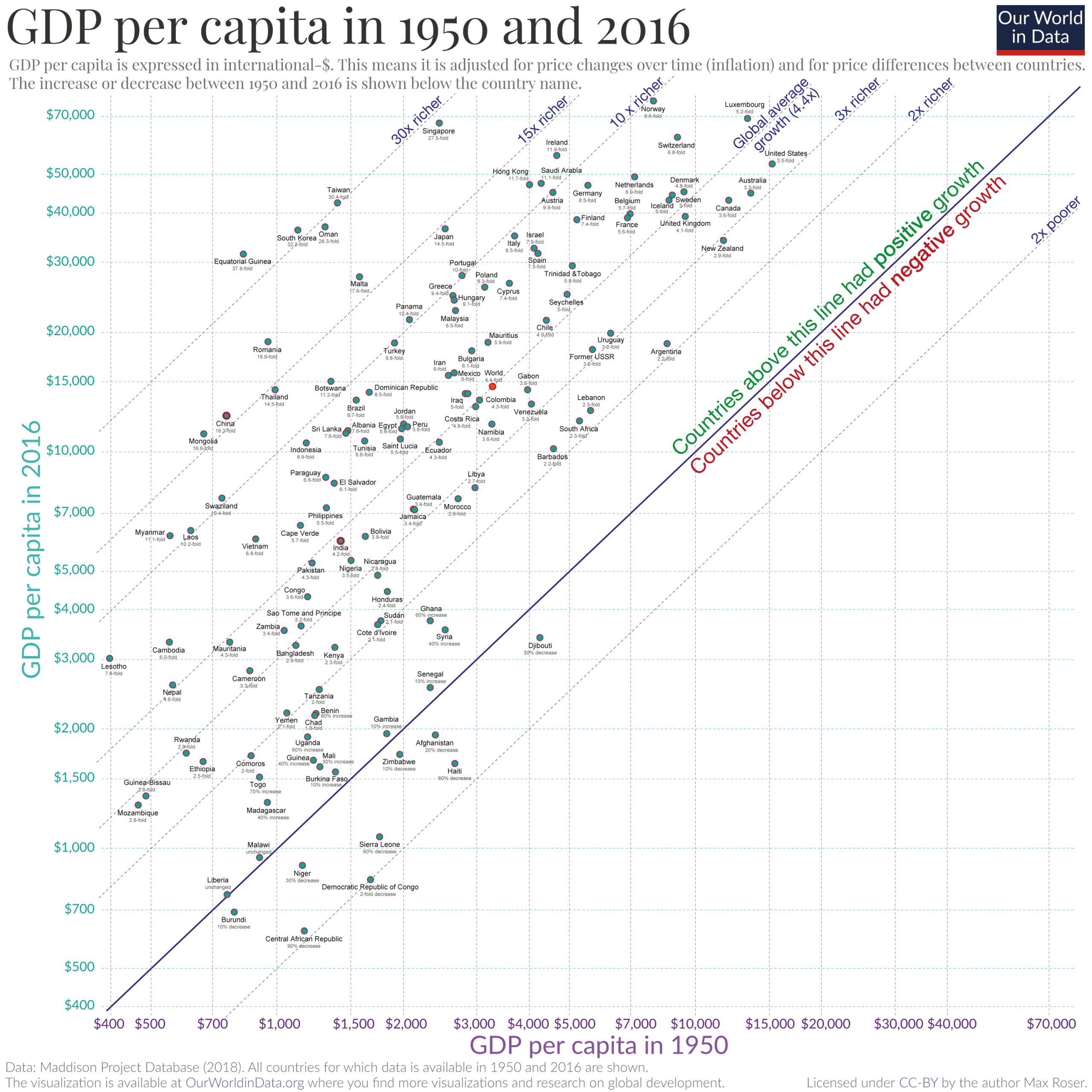

The chart below shows the level of GDP per capita for countries around the world between 1950 and 2016. On the vertical axis you see the level of prosperity in 1950 and on the horizontal axis you see it for 2016.

GDP – Gross Domestic Product – measures the total production of an economy as the monetary value of all goods and services produced during a specific period, mostly one year. Dividing GDP by the size of the population gives us GDP per capita to measure the prosperity of the average person in a country. Because all expenditures in an economy are someone else’s income we can think of GDP per capita as the average income of people in that economy. Here at Core-Econ you find a more detailed definition.

Look at the world average in the middle of the chart. The income of the average person in the world has increased from just $3,300 in 1950 to $14,574 in 2016. The average person in the world is 4.4-times richer than in 1950.

This takes into account that the prices of goods and services have increased over time (it is adjusted for inflation; otherwise these comparisons would be meaningless). Similarly, to allow us to compare prosperity between countries, all incomes are adjusted for differences in the cost of goods between different countries (using purchasing power parity conversion factors). As a consequence of these two adjustments incomes are expressed in international-dollars in 2011 prices, which means that the incomes are comparable to what you would have been able to buy with US-dollars in the USA in 2011.

While the global average income grew 4.4-fold, the world population increased 3-fold, from around 2.5 billion to almost 7.5 billion today.1

It’s easy to miss what this means: Had the world economy not grown, a 3-fold increase of the world population would have meant that on average everyone in the world would now be 3-times poorer than in 1950. The average income in the world would have fallen to $1,100. Before economic growth the world was exactly this: a zero-sum game in which more people meant less for everyone else, and if one person is better off in a stagnating economy then that means that someone else needs to be worse off (I wrote about it here).

What economic growth makes possible is that everyone can become better off, even when the number of people that need to be served by the economy increases.2 An almost 3-fold increase of the population multiplied by a 4.4-fold increase in average prosperity means that the global economy has grown 13-fold since 1950.3

The worst off today are those that lagged behind and remained in poverty

Incomes did not grow everywhere in the world. If you look at the poorest countries in the world today you’ll see that these countries did not stand out back in 1950; their incomes were as low as the incomes of many other countries in the world. But today they do – while many economies achieved strong growth some stagnated around their level from 1950. These are the countries that remained at the bottom of the chart. The difference between stagnation or even decline in some places and rapid growth in other places lead to a dramatic increase in inequality in the world. Norwegians are now on average more than 100-fold richer than people in Liberia, Burundi, and the Central African Republic.

This failure to grow the economy and to provide the goods and services that they need is one of the largest failures in recent decades. It means that populations in these places are now much worse off than people in the rest of the world – they are less healthy and die sooner, education is poorer, and many suffer from malnutrition.4

In most places people today are much richer than our ancestors

Economic growth has allowed us to break out of the conditions of the past when everyone was stuck in poor health, hard and monotonous work, and malnutrition. The chart below shows all economies that have achieved growth since 1950 above the diagonal 45°-line.

Taiwan is one of the most impressive examples. The Taiwanese had an income of $1,400 in 1950. All countries directly below Taiwan – Malta, Bolivia, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of Congo for example – were similarly poor in 1950. By 2016 GDP per capita in Taiwan had increased to $42,300. The Taiwanese are now among the richest people in the world, 30-times richer than they were in 1950. It is hard to imagine what this meant for living conditions in the country. To take just one example. Every sixth child born in Taiwan in 1950 died before it was five years old (13%). Today the child mortality rate has declined to half a percent (1-in-200 children).

Another way to look at it is to start with the richest people in the past – shown furthest to the right in the chart below. In 1950 the country with the highest average income was the USA with a GDP per capita of $15,241 (and they had just became prosperous in the few decades before; before some economies achieved sustained economic growth, income differences between different regions were very small and the vast majority of people were extremely poor).

If you look at incomes today then you find that the income in the richest country in 1950 is very close to the average income of the average person in the world today ($14,570). Today the average person on the planet is as rich as the the average person in the richest country in 1950. And all those countries that have an income higher than the global average today are more prosperous than the US in 1950: Iran, Mexico, Bulgaria, … Have a look at that list.

The same is true for health globally. The average life expectancy in the world today is 71 years, just 1 year less than the life expectancy in the very best off places in 1950. I wrote about it here.

In this post I looked at the population-wide average income. But, the question of how prosperity is shared among the population is an important one and it has been central to my research over the last years:If you are interested in this question, have a look at the short article on Vox.com that I have written with my colleague Stefan Thewissen here or other recent research of mine.5

Brian Nolan has edited two books on the question which were published just recently.

What this research shows is that it very much differs between countries and over time who is benefiting from economic growth. While in the US, for example, most of the income gains went to the richest members of society this is not true of other countries where economic growth was widely shared among all.

The data visualized in these two charts shows that the world is not the zero-sum economy that it was in our long past. It is not the case anymore that one person’s or one country’s gain is automatically another one’s loss. Economic growth transformed the world into a positive sum economy where more people can have access to more goods and services at the same time.

It would be wrong to focus on economic growth only. That is the reason why Our World in Data does not only look at this metric, but at hundreds of aspects – including health, education, humanity’s impact on the environment, and human and political rights. And there are alternatives to GDP per capita as a key metric and we’ve written about some of them before (here and here).

Economic growth has to be achieved at a time when we urgently have to reduce our impact on the environment. This means that it is not only the rate of growth that matters. As Mariana Mazzucato says “economic growth has not only a rate but also a direction”. And many paths for growth point in a direction that does not increase our environmental damage and instead can often reduce the impact (better care for the sick and elderly, better educational institutions, alternatives to meat, care for mental health, improved solar technology; all these improvements would mean more growth).

Economic growth is not the only thing that matters, but it does matter. In contrast to many of the other metrics on Our World in Data, economic growth does not matter for its own sake, but because rising prosperity is a means for many ends. It is because a person has more choices as their prosperity grows that economists care so much about growth. Rising prosperity gives people access to a wide range of things they value: food, healthcare, access to education, entertainment, holidays, free time, and more. The concern with GDP per capita is based on the idea that rising prosperity makes for a richer life. I find the metric important because it is a measure of means only and thereby respects the freedom of everyone to choose for themselves. It is because of this that is so important to track how incomes have changed around the world.

If you want to explore the change over time for a particular country, just click on the country in the map.