- In this post I am looking at projections of global extreme poverty until 2030: Projections from different research teams come to similar expectations.

- A generation ago the majority of the world’s poorest lived in economies that went on to grow very fast. What is different now is that a high share of the world’s poorest are living in economies which have not achieved economic growth in the recent past.

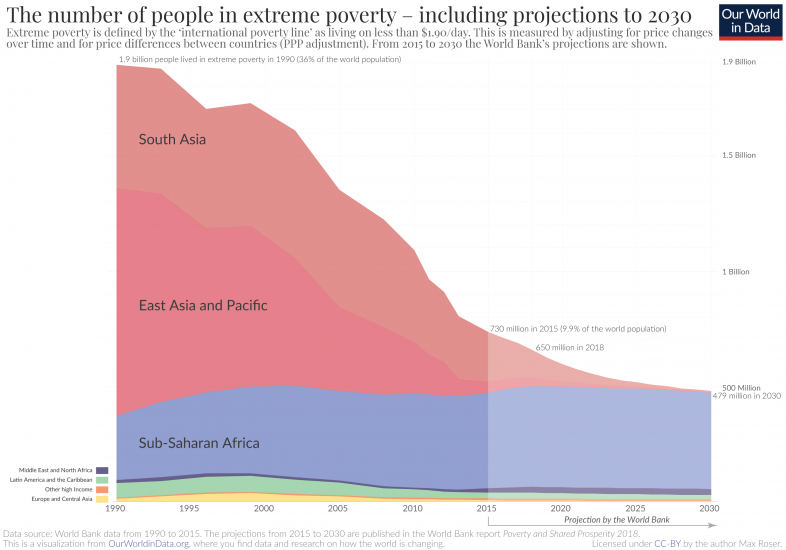

- Half a billion are expected to remain in extreme poverty by 2030 if current trends of economic growth and levels of within-country inequality persist.

- The decline of extreme poverty is expected to slow down. Much of the progress will be driven by economic growth in Asia, and India in particular. The number of people in extreme poverty in Africa is expected to stagnate.

Over the course of the last generation more than one billion people left the most destitute living conditions behind. Can we expect this rapid progress to continue over the coming decade?

The world economy is growing. In less than a generation the value of the yearly global economic production has doubled.1

Increasing productivity around the world meant that many left the worst poverty behind. More than a third of the world population now live on more than 10 dollars per day, as the visualization below shows. Just a decade decade ago it was only a quarter. In absolute numbers this meant the number of people who live on more than 10 dollars per day increased by 900 million in just the last 10 years.2

This expansion of the global middle class went together with progress in reducing global poverty – no matter what poverty line you want to compare it with, the share of the world population below this poverty line declined.3 In 1990 international organizations adopted a definition of poverty in line with the poverty lines in low-income countries. In the latest adjustment the international poverty line is set to the threshold of living on less than $1.90 per day. That is a very low poverty line and focusses on what is happening to the very poorest people on the planet.4

The same international organizations that set the poverty line made it a global goal to end extreme poverty – here is the UN’s page on the topic. Goal number one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agreed on by all nations in the world, is the “eradication of extreme poverty for all people everywhere”. The deadline for achieving this goal is 2030. Can we expect to achieve this?

Research teams from the World Bank, ODI, the IHME, and Brookings jointly with the World Data Lab made independent projections for what we can expect for global poverty during the SDG era.

While the projections differ in methodology and underlying assumptions, it’s striking how much they align in their projection for what to expect in the coming decade if the world stays on current trajectories. All expect some positive development – the number of people in extreme poverty is expected to continue to decline – but all also agree that the world is not on track to end extreme poverty by 2030.

The chart shows the projection made by the development research team at the World Bank. This projection answers the question of what would happen to extreme poverty trends if the economic growth of the past decade (2005–15) continued until 2030:5 The number of people in extreme poverty will remain at almost 500 million.

This is not because it is not possible to end extreme poverty. In more than half of the countries of the world the share of the population in extreme poverty is now less than 3 percent.6 In the same countries the huge majority – even in today’s richest countries – lived in extreme poverty just a few generations ago.

In fact, a big success over the last generation was that the world made rapid progress against the very worst poverty. The number of people in extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 1.9 billion in 1990 to about 650 million in 2018.7

This was possible as economic growth reached more and more parts of the world.8 In Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Ghana, and China more than half the population lived in extreme poverty a generation ago. But after two decades of growth the share in extreme poverty more than halved in all these countries.

Poverty was not concentrated in Africa until recently. In 1990 more than a billion of the extremely poor lived in China and India alone. Since then those economies have grown faster than many of the richest countries in the world. The concentration of the world’s poorest shifted from East Asia in the 1990s to South Asia in the following decade. Now it has shifted to Sub-Saharan Africa. The projections suggest the geographic concentration of extreme poverty is likely to continue. According to the World Bank forecasts 87% of the world’s poorest are expected to live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2030 if economic growth follows the trajectory over the recent past.

Poverty declined during the last generation because the majority of the poorest people on the planet lived in countries with strong economic growth. This is now different.

Many of the world’s poorest today live in countries that had very low economic growth in the past.9 Consider the case of Madagascar: In the last 20 years GDP per capita has not grown; and the number in extreme poverty increased almost one-for-one with total population.

Development economists have emphasized this for some time: The very poorest people in the world did not see their material living conditions improve.10 This fact is surely one of the biggest development failures of our time. Yet the stagnation of the world’s poorest countries is not as widely known as it should be – one reason is that we are not paying attention to poverty lines low enough to focus on what happens to the very poorest. This is an important reminder that one poverty line is not enough and we need to rely on several poverty lines – higher and lower than the international poverty line – to understand how the world is changing.

A rising global middle class and stagnation of the world’s poorest will also mean that a new divide at the lowest end of the global income distribution is opening up. We miss this if we only follow what is happening to the rapidly emerging global middle class or if we rely on global poverty lines that are not capturing what is happening to the poorest.

The projections suggest that over the coming decade the stagnation at the bottom will become very clear. The majority of the world’s poorest today live in economies that are not growing and half a billion face the prospect to remain stuck in extreme poverty.

This is terrible news.

These projections are not predictions, their purpose is not to describe what we believe the world in 2030 will look like. These projections describe what we have to expect on current trends and as that they tell us about our present world rather than the reality of tomorrow. And key point there is that current trends don’t have to become future trends: all countries that left extreme poverty behind had a moment at which they broke out of stagnation.

The big lesson from the history of extreme poverty is that it is the growth of an entire economy that lifts individuals out of poverty. Key for ending extreme poverty globally will be that the poorest countries achieve the difficult task of economic growth.

But it’s not only about macroeconomic performance. Social policy and direct household-level support, too, make an important difference. Even in very poor economies there is scope for targeted policies to support the very poorest. In an analysis of how today’s richest countries left extreme poverty behind Martin Ravallion emphasizes the role the expanded social protection policies played at the time.11

The most important task in our time is to ensure that the living conditions of the world’s poorest improve and to end extreme poverty. We know that it is possible; we have done it many times in the past.

Over the course of the last generation global extreme poverty declined rapidly, but many are still very poor and progress against extreme poverty is urgently needed. However, we are currently far off track to ending extreme poverty – we expect half a billion people to still live on less than $1.90 per day by 2030. To ensure that ‘no one is left behind’ as the SDG agenda promises, this is where we need to focus our efforts.

And this is not just a concern until 2030: without rising incomes in the worst-off places extreme poverty will remain a reality.

If you are interested in the projections by Jesus Crespo Cuaresma et al. from the World Data Lab you find them in my slides for the UN from last year.