In 1938, a group of Harvard researchers decided to start a research program to track the lives of a group of young men, in what eventually became one of the longest and most famous longitudinal studies of its kind. The idea was to track the development of a group of teenage boys through periodic interviews and medical checkups, with the aim of understanding how their health and well-being evolved as they grew up.1

Today, more than 80 years later, it is one of the longest running research programmes in social science. It is called the Harvard Study of Adult Development and it is still running. The program started with 724 boys, and researchers continue to monitor today the health and well-being of those initial participants who are still alive, most in their late 90s.2

This is a unique scientific exercise – most longitudinal studies do not last this long because too many participants drop out, researchers move on to other projects (or even die), or the funding dries up.

So what have we learned from this unique study?

Robert Waldinger, the current director of the study, summarized – in what is now one of the most viewed TED Talks to date – the findings from decades of research. The main result, he concluded, is that social connections are one of the most important factors for people’s happiness and health. He said: “Those who kept warm relationships got to live longer and happier, and the loners often died earlier”.

Here I take a closer look at the evidence and show more research that finds a consistent link between social connections and happiness. But before we get to the details, let me explain why I think this link is important.

As most people can attest from personal experience, striving for happiness is not easy. In fact, the search for happiness can become a source of unhappiness – there are studies that show actively pursuing happiness can end up decreasing it.

The data shows that income and happiness are clearly related; but we also know from surveys that people often overestimate the impact of income on happiness. Social relations might be the missing link: In rich countries, where minimum material living conditions are often satisfied, people may struggle to become happier because they are targeting material rather than social goals.

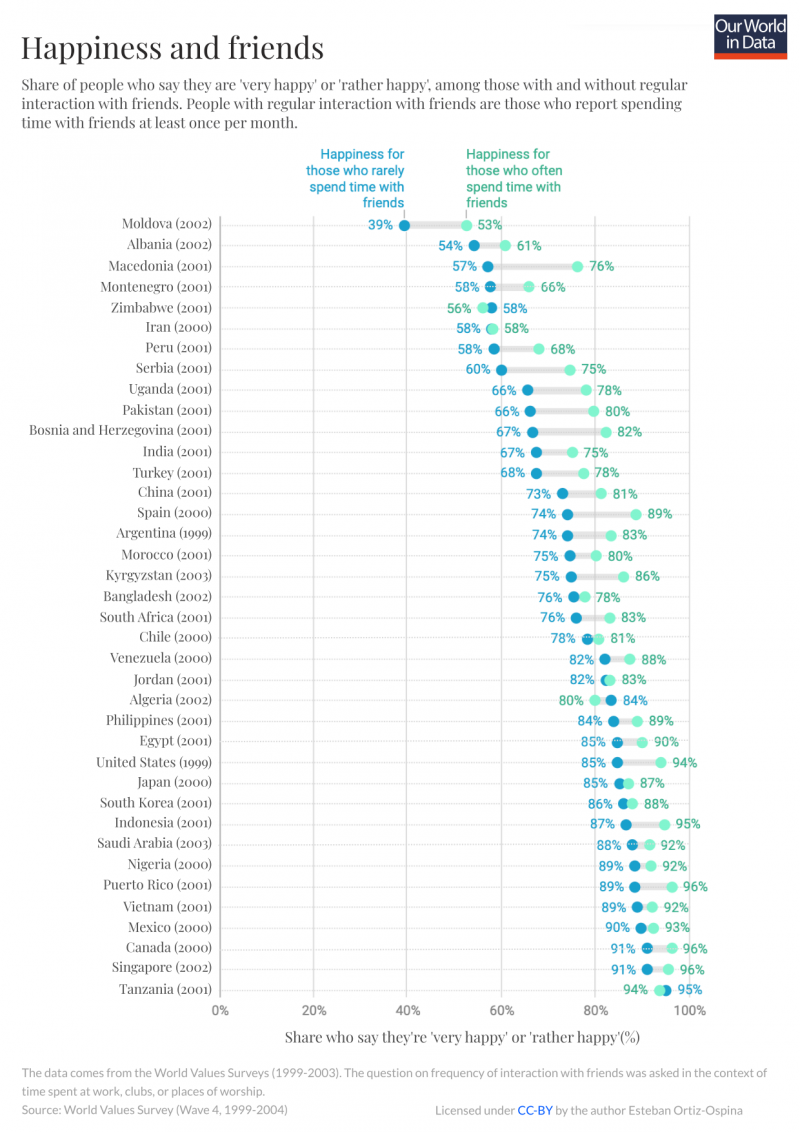

The World Value Survey (WVS) is a large cross-country research project that collects data from a series of representative national surveys. In the fourth wave (1999-2004) the WVS asked respondents hundreds of questions about their lives, including whether they were part of social or religious groups, how often they spent time with friends, and whether they felt happy with their life.

By comparing self-reported happiness among those with and without frequent social interactions, we can get an idea of whether there is indeed a raw correlation between happiness and social relations across different societies.

In the chart below I show this comparison: The green points correspond to happiness among those who interact with friends at least once per month; while the blue dots correspond to happiness among those who interact with friends less often.3

This chart shows that in almost all countries people who often spend time with their friends report to be happier than those who spend less time with friends.4

The chart above gives a cross-sectional perspective – it’s just a snapshot that compares different people at a given point in time. What happens if we look at changes in social relations and happiness over time?

There is a large academic literature in medicine and psychology that shows individuals who report feelings of loneliness are more likely to have health problems later in life (you can read more about this in my post here); and similarly, there are also many studies that show that changes in social relations predict changes in happiness and life satisfaction.

One of the research papers that draws on data from the famous Harvard Study of Adult Development, for example, looked at the experiences of 82 married participants and their spouses, and found that greater self-reported couple attachment predicted lower levels of depression and greater life satisfaction 2.5 years later.5

Other studies with larger population samples have also found a similar cross-temporal link: perceived social isolation predicts subsequent changes in depressive symptoms but not vice versa, and this holds after controlling for demographic variables and stress.6

Searching for happiness is typically an intentional and active pursuit. Is it the case that people tend to become happier when they purposely decide to improve their social relations?

This is a tough empirical question to test; but a recent study found evidence pointing in this direction.

Using a large representative survey in Germany, researchers asked participants to report, in text format, ideas for how they could improve their life satisfaction. Based on these answers, the researchers then investigated which types of ideas predicted changes in life satisfaction one year later.

The researchers found that those who reported socially-engaged strategies (e.g. “I plan to spend more time with friends and family”) often reported improvements in life satisfaction one year later; while those who described other non-social active pursuits (e.g. “I plan to find a better job”) did not report increased life satisfaction.7

From decades of research we know that social relations predict mental well-being over time; and from a recent study we also know that people who actively decide to improve their social relations often report becoming happier. So yes, people are happier when they spend more time with friends.

Does this mean that if we have an exogenous shock to our social relations this will have a permanent negative effect on our happiness?

We can’t really answer this with the available evidence. More research is needed to really understand the causal mechanisms that drive the link between happiness and social relations.8

Despite this, however, I think that we should take the available observational evidence seriously. In a way, the causal impact from a random shock is less interesting than the evidence from active strategies that people might take to improve their happiness. People who get divorced, for example, often report a short-term drop in life satisfaction; but over time they tend to recover and eventually end up being more satisfied with their life than shortly before they divorced (you can read more about this in our entry on happiness and life satisfaction).

It makes sense to consider the possibility that healthy social relationships are a key missing piece for human wellbeing. Among other things, this would help explain the paradoxical result from studies where actively pursuing happiness apparently ends up decreasing it.