Literacy is a key skill and a key measure of a population’s education. In this entry we discuss historical trends, as well as recent developments in literacy.

From a historical perspective, literacy levels for the world population have risen drastically in the last couple of centuries. While only 12% of the people in the world could read and write in 1820, today the share has reversed: only 14% of the world population, in 2016, remained illiterate. Over the last 65 years the global literacy rate increased by 4% every 5 years – from 42% in 1960 to 86% in 2015.1

Despite large improvements in the expansion of basic education, and the continuous reduction of education inequalities, there are substantial challenges ahead. The poorest countries in the world, where basic education is most likely to be a binding constraint for development, still have very large segments of the population who are illiterate. In Niger, for example, the literacy rate of the youth (15-24 years) is only 36.5%.

All our charts on Literacy

Of the world population older than 15 years 86% are literate. This interactive map shows how the literacy rates varies between countries around the world.

In many countries more than 95% have basic literacy skills. Literacy skills of the majority of the population is a modern achievement as we show below.

Globally however, large inequalities remain, notably between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world. In Burkina Faso, Niger and South Sudan – the African countries at the bottom of the rank – literacy rates are still below 30%.

While the earliest forms of written communication date back to about 3,500-3,000 BCE, literacy remained for centuries a very restricted technology closely associated with the exercise of power. It was only until the Middle Ages that book production started growing and literacy among the general population slowly started becoming important in the Western World.2 In fact, while the ambition of universal literacy in Europe was a fundamental reform born from the Enlightenment, it took centuries for it to happen. It was only in the 19th and 20th centuries that rates of literacy approached universality in early-industrialized countries.

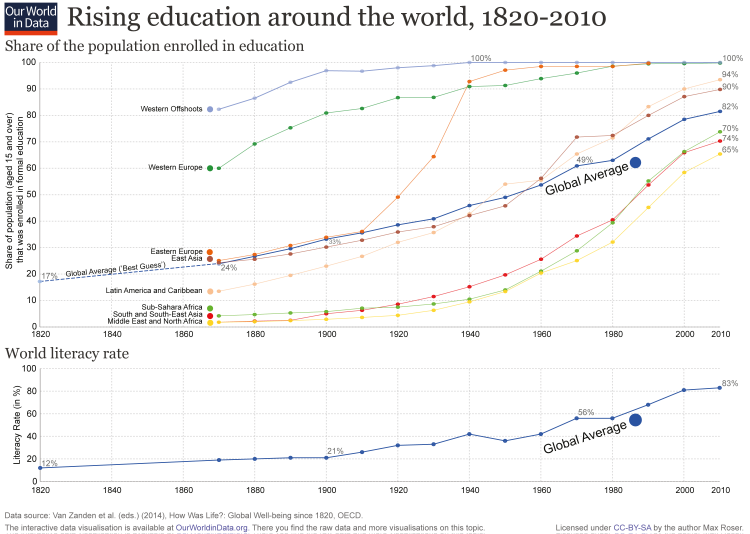

The following visualization presents estimates of world literacy for the period 1800-2016. As we can see, literacy rates grew constantly but rather slowly until the beginning of the twentieth century. And the rate of growth really climbed after the middle of the 20th century, when the expansion of basic education became a global priority. You can read more about the expansion of education systems around the world in our entry on Financing Education.

The following visualization shows the spread of literacy in Europe since the 15th century, based on estimates from Buringh and Van Zanden (2009).3

As it can be seen, the rising levels of education in Europe foreshadowed the emergence of modern societies.

Particularly fast improvements in literacy took place across Northwest Europe in the period 1600-1800. As we discuss below, widespread literacy is considered a legacy of the Age of Enlightenment.

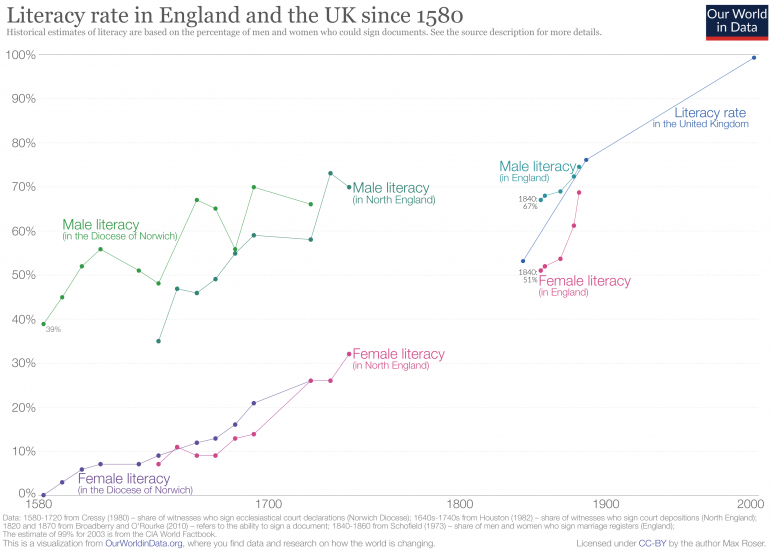

This chart shows historical estimates of literacy in England over the last five centuries.

The historical estimates are based on the percentage of men women who could sign documents, a very basic definition of literacy that is often used in historical research on education.4

The first observations refer to men and women in the diocese of Norwich, which lies to the Northeast of London. Here, the majority of men (61%) were unable to write their name in the late 16th century; for women it was much lower.

By 1840 two-thirds of men and about half of women were literate in England. The expansion of education led to a reduction in education gender inequality. Towards the end of the 19th century the share had increased to almost three-quarters for both genders.

As the center of the Industrial Revolution and one of the first countries that established democratic institutions, England was in important aspects the center of the development of modernity.

The data shows that improvements in literacy preceded the Industrial Revolution and in many ways the rise of living standards became only possible thanks to an increasingly better educated public. Economic growth is possible when we better understand how to produce the things we need, and translate these insights into technological improvements that allow us to produce them more efficiently. Both the development of new technologies (innovation) and their use in production relied on a much better-educated population.

Widespread school education and even basic skills like literacy are a very recent achievement that was enabled and at the same time required by the progress achieved in recent generations.

The visualization shows, in two panels, a side-by-side comparison of long-term trends in school attendance and literacy.

We can see that in 1870 only one in four people in the world attended school, and this meant that only one in five were able to read. And global inequalities in access to education were very large.

Today, in contrast, the global estimates of literacy and school attendance are above 80%, and the inequality between world regions – while still existing – is much lower.

We can see that two centuries ago only a small elite of the world population had the ability to read and write – the best estimate is that 12% of the world population was literate. Over the course of the 19th century global literacy more than doubled. And over the course of the 20th century the world achieved rapid progress in education. More than 4 out of 5 people are now able to read. Young generations are better educated than ever before.

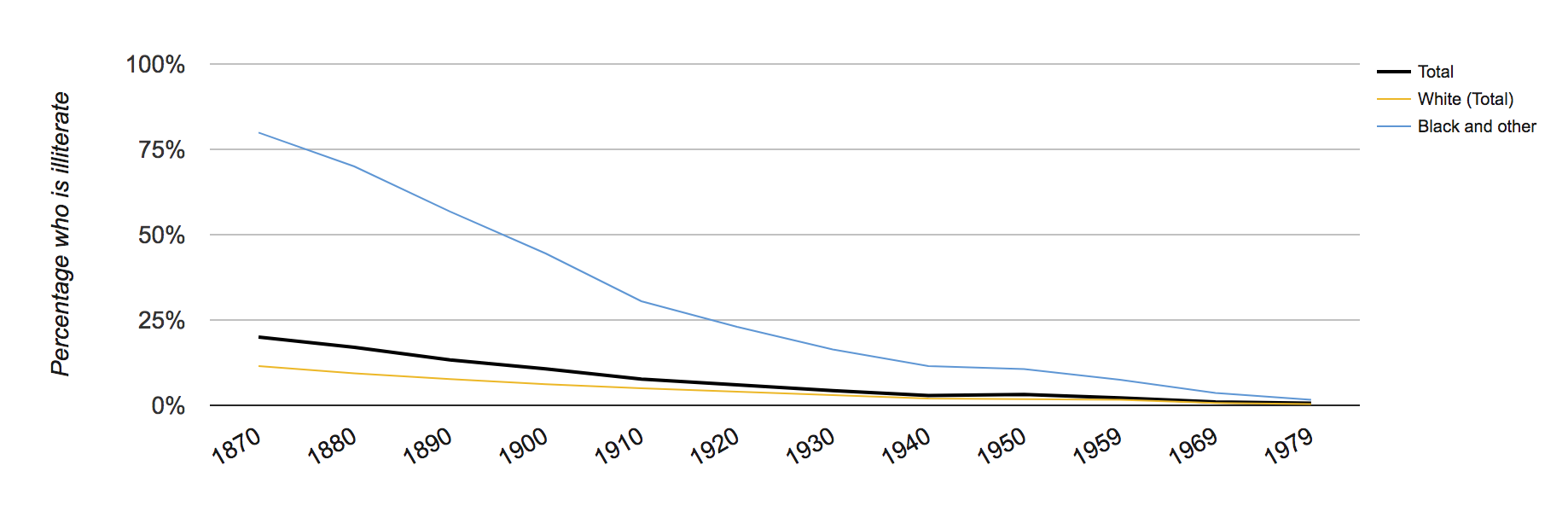

The expansion of literacy in early-industrialized countries helped reduce within-country inequalities. In the preceding visualization we showed that England virtually closed literacy gender gaps by 1900. Here we provide evidence of literacy gaps across races in the US.

The following visualization shows illiteracy rates by race for the period 1870-1979. As we can see, in order to reach near universal levels of literacy, the US had to close the race gap. This was eventually achieved around 1980.

Percentage of persons 14 years old and over in the US who were illiterate by race, 1870-1979 – Our World in Data, with data from NCES5

As pointed out above, Europe pioneered the expansion of basic education – but global literacy rates only started really climbing in the second half of the 20th century, when the expansion of basic education became a global priority. Here we present evidence of important recent achievements in Latin America, where literacy has dramatically increased in the past century.

As it can be seen, many nations have gained 40-50 percentage points in literacy during this period.

Despite these improvements, however, there is still a wide disparity between nations. Here you can see that, at the turn of the 21st century, half of the population in poor countries such as Haiti remains illiterate. This motivates the next visualization, where we discuss cross-country heterogeneity in more detail.

Literacy by generation

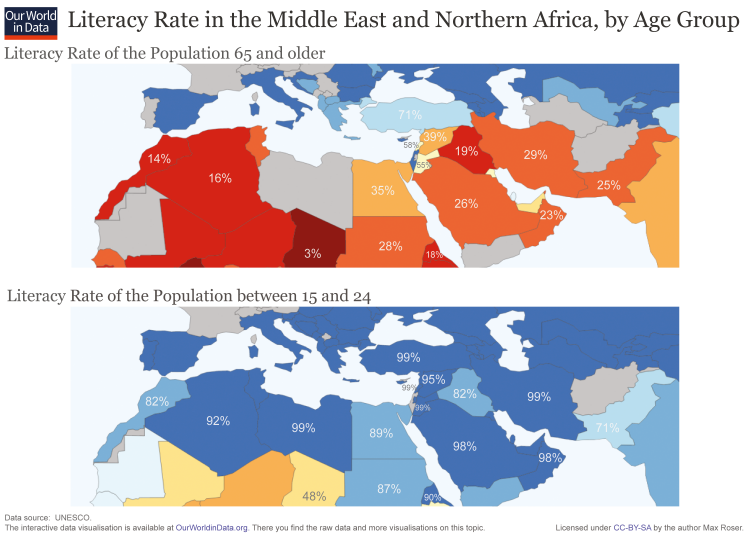

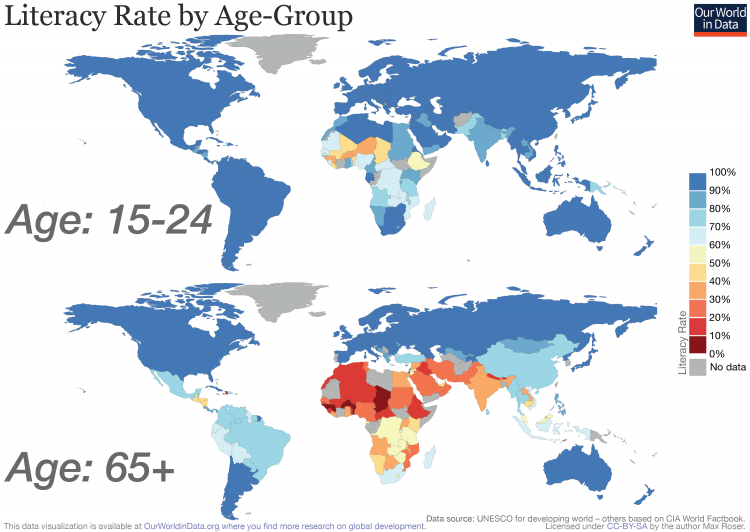

To assess the extent to which progress can be expected in the years to come, it is convenient to break down literacy estimates by age groups. The following map, using data from UNESCO, shows such estimates for most countries in the world.

As it can be seen, in the majority of nations there is a large difference in literacy rates across generations (you can change the map to show literacy rates for different groups by clicking on the corresponding buttons at the top).

These large differences across generations point to a global trend: the high literacy rate among the youth indicates that as time passes, the literacy rate for the overall population will continue to increase.

World maps of the literacy rate by age group6

We highlighted above the fact that most low and middle income countries feature large differences in literacy rates across generations. The visualization shows specifically how remarkably large these differences are in Northern Africa and the Middle East. Using UNESCO data, these maps show that in many countries in these regions, only less than a third of the older generation is literate – while in contrast, more than 90% of the younger generation is literate.

The scatter plot emphasises the point already made. As you can see, younger generations are more likely to be literate than older generations around the world. And in some countries the gaps are dramatic. In Algeria, for example, the literacy rate among the youth (15-24 years) is close to 97%; while it is 28% among the older population (65+ years).

In the chart you can use the slider at the bottom to check how these generational gaps have been changing in recent decades. You can see that throughout Africa the changes have been mainly horizontal (i.e. gaps have been widening as there have been radical recent improvements specifically benefiting the younger population). This is in contrast to richer regions, such as Europe, where the expansion of education started earlier and as a consequence changes have been mainly vertical (e.g. in Portugal the literacy rate among the youth was already high in 1980; so continued education expansion has meant that literacy rates are today almost equally high across the entire Portuguese population).

Literacy by sex

The visualization shows that particularly in many poorer countries the literacy rate for young women is lower than the rate for young men.

This chart shows the literacy rate by sex over time.

This visualization shows the ratio of the literacy rate between young women and men around the world.

Numeracy is the ability to understand and work with numbers. The visualization shows how this basic ability became more common in populations around the world based on a very basic definition of numeracy, the ability to correctly state one’s own age.

Compared to the data on literacy we have less information on numeracy skills in the world today. Some information comes from PIAAC, the OECD’s survey of the skills of adults. A world map of these scores can be found here.

The scatter plot shows how adults in OECD countries scored in the literacy and numeracy dimension. We see that the two aspects are closely correlated, those countries that have high literacy also have high numeracy.

PIAAC is only available for the very recent past, but it can still give us some insights of how numeracy skills in the world have changed. If we compare the numeracy scores of the young cohort with the older cohort in a scatterplot we find that in most countries numeracy skills have recently increased.

Measurement today

In the chart we present a breakdown of UNESCO literacy estimates, showing the main methodologies used, and how these have changed over time. (To explore changes across time use the slider underneath the map.)

The breakdown covers four categories: self-reported literacy declared directly by individuals, self-reported literacy declared by the head of the household, tested literacy from proficiency examinations, and indirect estimation or extrapolation.

In most cases, the categories covering ‘self-reports’ (green and orange) correspond to estimates of literacy that rely on answers provided to a simple yes/no question asking people if they can read and write.

The category ‘indirect estimation’ (black) corresponds mainly to estimates that rely on indirect evidence from educational attainment, usually based on the highest degree of completed education.

In this table you find details regarding all literacy definitions and sources, country by country, and how we categorised them for the purpose of this chart.

This chart is telling us that:

- There is substantial cross-country variation, with recent estimates covering all four measurement methods.

- There is variation within countries across time (e.g. Mexico switches between self-reports and extrapolation).

- The number of countries that base their estimates on self-reports and testing is increasing.

Another way to dissect the same data, is to classify literacy estimates according to the type of measurement instrument used to collect the relevant data. In the next chart we explore this, splitting estimates into three categories: sampling, including data from literacy tests and household surveys; census data; and other instruments (e.g. administrative data on school enrollment).

Here we can see that most countries use sampling instruments (coded as ‘surveys’ in the map), although in the past census data was more common. Literacy surveys have the potential of being more accurate – when the sampling is done correctly – because they allow for more specific and detailed measurement than short and generic questions in population censuses.

As mentioned above, recent data on literacy is often based on a single question included in national population censuses or household surveys presented to respondents above a certain age, where literacy skills are self-reported. The question is often phrased as “can you read and write?”. These self-reports of literacy skills have several limitations:

- Simple questions such as “can you read and write?” frame literacy as a skill you either possess or do not when, in reality, literacy is a multi-dimensional skill that exists on a continuum.

- Self-reports are subjective, in that the question is dependent on what each individual understands by “reading” and “writing”. The form of a word may be familiar enough for a respondent to recall its sound or meaning without actually ‘reading’ it. Similarly, when writing out one’s name to convey written ability, this can be accomplished by ‘drawing’ a familiar shape rather than writing in an effort to produce a written text with meaning.

- In many cases surveys ask only one individual to report literacy on behalf of the entire household. This indirect reporting potentially introduces further noise, in particular when it comes to estimating literacy among women and children, since these groups are less often considered ‘head of household’ in the surveys.

Similarly, inferring literacy from data on educational attainment is also problematic, since schooling does not produce literacy in the same way everywhere: Proficiency tests show that in many low-income countries, a large fraction of second-grade primary-school students cannot read a single word of a short text; and for very few people in these countries going to school for four or five years guarantees basic literacy.

Even at a conceptual level there is lack of consensus – national definitions of literacy that are based on educational attainment vary substantially from country to country. For example, in Greece people are considered literate if they have finished six years of primary education; while in Paraguay you qualify as literate if you have completed two years of primary school.7

Given the limitations of self-reported or indirectly inferred literacy estimates, efforts are being made at both national and international levels to conduct standardized literacy tests to assess proficiency in a systematic way.

In particular, large cross-country assessment surveys have been developed to overcome the challenges of producing comparable literacy data. Two important examples are the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), which is a test used for measuring literacy mostly in rich countries; and the Literacy Assessment and Monitoring Programme (LAMP), which is a household assessment aimed at measuring literacy skills in developing countries, while remaining comparable across countries, languages, and scripts.8

The LAMP tests have only recently been field tested in four countries: Jordan, Mongolia, Palestine, and Paraguay. The PIAAC tests, on the other hand, have been administered in about 30 countries, and the results are shown in the chart.9

We only have these tests for a few countries, but we can still see that there is an overall positive correlation. Moreover, we see that there is substantial variation in scores even for countries with identical and almost perfect literacy rates (e.g. Japan vs Italy). This confirms the fact that PIAAC tests capture a related, but broader concept of literacy.

Reconstructing estimates from the past

The UNESCO definition of “people who can, with understanding, read and write a short, simple statement on their everyday life”, started being recorded in census data from the end of the 19th century onwards. Hence, despite variation on the types of questions and census instruments used, these historical census data remain the best source of data on literacy for the period prior 1990.

The longest series attempting to reconstruct literacy estimates from historical census data is provided in the OECD report “How Was Life? Global Well-being since 1820”, published in 2014. This is the source used in the first chart in this blog post for the period 1800 to 1990.10

How accurate are these UNESCO estimates?

The evidence suggests that the narrow concept of literacy measured in early census data provides an imperfect, yet informative account of literacy skills. The chart shows a good example: As we can see, already in 1947, census estimates from the US correlate strongly with educational attainment, as one would expect.

Importantly, the correlation between educational attainment and literacy also holds across countries and over time. The next chart shows this by plotting changes in literacy rates and average years of schooling. Each country in this chart is represented by a line, where the beginning and ending points correspond to the first and last available observation of these two variables over the period 1970-2010. (As we mention above, before 1990 almost all observations correspond to census data.)

As we can see, literacy rates tend to be much higher in countries where people tend to have more years of education; and as average years of education go up in a country, literacy rates also go up.

Countries with high literacy rates also tend to have higher results in the basic literacy tests included in the DHS surveys (this is a test that requires survey respondents to read a sentence showed to them). As we can see in the chart, there is obviously noise, but these two variables are closely related.

When census data is not available, a common method used to estimate literacy is to calculate the share of people who could sign official documents (e.g. court documents, marriage certificates, etc).11

As the researcher Jeremiah Dittmar explains, this approach only gives a lower bound of the estimates because the number of people who could read was higher than the number who could write.

Indeed, other methods have been proposed, in order to rely on historical estimates of people who could read. For example, researchers Eltjo Buringh and Jan Luiten van Zanden deduce literacy rates from estimated per capita book consumption. 12 As Buringh and Van Zanden show, their estimates based on book consumption are different, but still fairly close to alternative estimates based on signed documents.

- Data: Literacy rate for the entire population

- Geographical coverage: Global – by country

- Time span: 2011 or most recent earlier estimate (in some cases going back several decades)

- Available here

- Data: Literacy rate (for youths (15-24), adults (15+) and the elderly population (65+))

- Geographical coverage: Global – by country

- Time span: Since 1975 – scattered and far from annual data

- Available at: It is online here, and it is visualized here.

- The UNDP’s Human Development Report data is here, and UNICEF publishes data on literacy rate here.

- Older older publications including data on literacy rates are:

UNESCO (2002) – Estimated Illiteracy Rate and Illiterate Population Aged 15 Years and Older by Country, 1970–2015, Paris.

UNESCO (1970) – Literacy 1967–1969 Progress Achieved in Literacy Throughout the World. Paris (1970)

UNESCO (1957) – World illiteracy at mid-century – A Statistical Study, Paris.

UNESCO (1953) – Progress of literacy in various countries – A Preliminary Statistical Study of Available Census Data since 1900, Paris.

- Data: Literacy rate

- Geographical coverage: Global – by country (not by region). There are almost no data for rich industrialized countries – only for developing countries.

- Time span: Since 1975 – scattered

- Available at:

- Annual data on ‘Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above)‘ – going back to 1975

- Annual data on ‘Literacy rate, youth total (% of people ages 15-24)‘ – going back to 1975 (this data is also published for males and females separately)

- This data is taken from the UNESCO.

- Data: Literacy rate

- Geographical coverage: Mostly Western Europe

- Time span: 19th and 20th century

- Available at: Two important publications are: Peter Flora (1983 & 1987) – State, Economy, and Society in Western Europe 1815–1975: A Data Handbook in two Volumes. Frankfurt, New York: Campus; London: Macmillan Press; Chicago: St. James Press and Peter Flora (1973) – Historical processes of social mobilization: urbanization and literacy, 1850–1965. In S.N. Eisenstadt, S. Rokkan (Eds.), Building States and Nations: Models and Data Resources, Sage, London, pp. 213–258.

- Data: Illiteracy rate (percent of adult population)

- Geographical coverage: Latin American countries

- Time span: Since 1900

- Available at: Online here

- Data: Measures of numeracy and literacy competence

- Geographical coverage: 24 OECD countries

- Time span: no time series dimension – only 2012

- Available at: Online here

- Presents the initial results of the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC)