This page is dedicated to the research why people are optimistic or pessimistic about certain things and how this is influenced by human nature, the media, and social circumstances.

We are interested in this topic also because it is closely linked to our motivation for publishing Our World in Data. We face big global problems, but living conditions around the world have improved in important ways; fewer people are dying of disease, conflict and famine; more of us are receiving a basic education; the world is becoming more democratic; we live longer and lead healthier lives.

Why is that we – especially those in the developed world – often have a negative view on how the world has changed over the last decades and centuries? Why we are so pessimistic about our collective future?

All our charts on Optimism and Pessimism

Individual optimism and social pessimism

It is a peculiar empirical phenomenon that while people tend to be optimistic about their own future, they can at the same time be deeply pessimistic about the future of their nation or the world. Tali Sharot, associate professor of psychology at UCL, has popularised the idea of an innate optimism bias built into the human brain.1

That is, we tend to be optimistic rather than realistic when considering our individual future. If you were to ask newlywed couples to estimate the probability they will divorce in the future, they would likely reject the possibility outright. Yet today roughly 40% of marriages in the UK end in divorce. Another example is asking smokers to estimate their chances of getting cancer and again, most would underestimate their risk. This optimism persists even when people are presented with the relevant statistics.

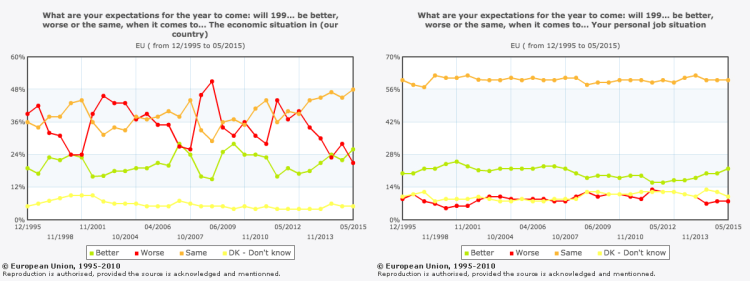

Consider the following graphs from the European Union’s Eurobarometer surveys; they report people’s expectations about their own personal job situation and of the economic situation in their home country. From the end of 1995 to the middle of 2015, around 60% of people predict that their job situation will remain the same, while 20% expect their situation to improve. Compare that with the response of the same group of individuals considering the future of the economic situation in their home country. Although far less stable, the results show that most people expect the economic situation in their home country to get worse or stay the same. The expectation that things are going to worsen nationally is correlated with recessions, yet there is remarkable stability in the results for individual expectations. Does the response to the question about national economic well being better correspond to an individual’s true job prospects?

EU survey responses on individual and economic optimism – Eurobarometer surveys2

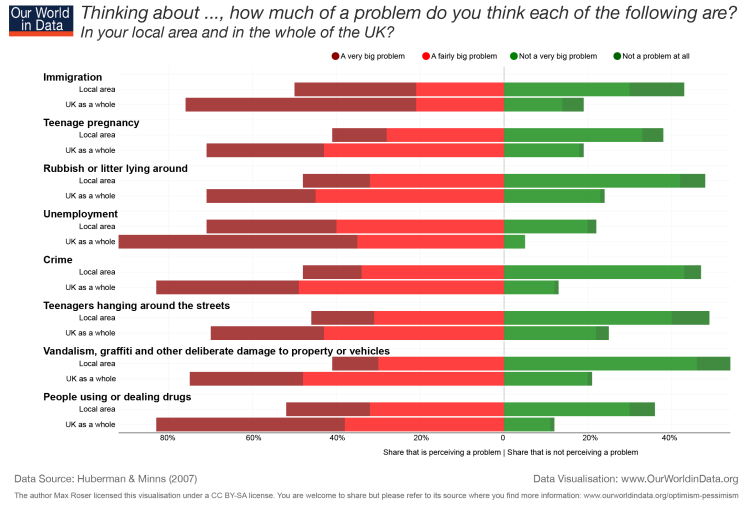

This pattern is also observed on a larger scale. This chart shows how individuals in the UK respond to the question: “Thinking about …, how much of a problem do you think each of the following are in your local area and in the whole of the UK?” Individuals tend to believe problems are more pronounced nationally than in their local area.

Local optimists and national pessimists in the UK, 2013 – Ipsos MORI3

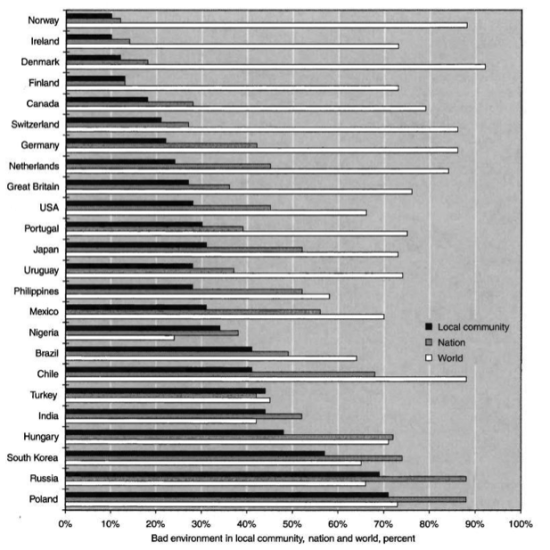

This chart shows how many individuals rate the environment in their local area as fairly or very bad, compared with the environment nationally and globally. Again, we observe a similar pattern for most countries. No matter where you ask people are much more negative about places that are far away – places which they know less from their own experience and more through the media.

Percentage of respondents who evaluate the environmental quality of their local community, their nation and the world as very or fairly bad – Lomborg (2001)4

How can we reconcile this individual optimism with social pessimism? Paul Dolan, professor of behavioural science at LSE, believes people respond pessimistically to questions about national or international performance for three reasons:

- Individuals rarely think about grand issues such as the state of the nation or world, and so respond with an ‘on-the-spot’ answer that may not be well considered or even a true reflection of their beliefs.

- The framing can influence the individual’s response. Moreover, the question itself may bias responses; ‘who would bother to ask if everything were okay?’

- Responses to questions such as these (and more general questions about happiness or life satisfaction) are heavily influenced by ephemeral recent events. In psychology this is referred to as the ‘availability bias’.

This explanation suggests there is a problem of information. If we do not pay attention to human development, then our judgement may suffer from a bias related to transient events or framing. The Gapminder Ignorance Project – which studied how wrong or right people are informed about global development – suggests the reason for all this ignorance is:

“Statistical facts don’t come to people naturally. Quite the opposite. Most people understand the world by generalizing personal experiences which are very biased. In the media the “news-worthy” events exaggerate the unusual and put the focus on swift changes. Slow and steady changes in major trends don’t get much attention. Unintentionally, people end-up carrying around a sack of outdated facts that you got in school (including knowledge that often was outdated when acquired in school).”

Another explanation put forward by Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests a link between control and optimism. If we feel more in control of our lives, we tend to be happier, healthier and more optimistic about the future. This could also help to explain the gap between individual and societal optimism: since we are in direct control of our own lives but not the destiny of the nation we feel more optimistic about ourselves.

Information matters: We are not only pessimistic about the future, we are also unaware of past improvements

At Our World in Data we aim to bring together the empirical data and research to show how living conditions around the world are changing. Is that necessary?

The opinion research organization Ipsos MORI conducted a detailed survey of 26,489 people across 28 countries that gives us an answer.5

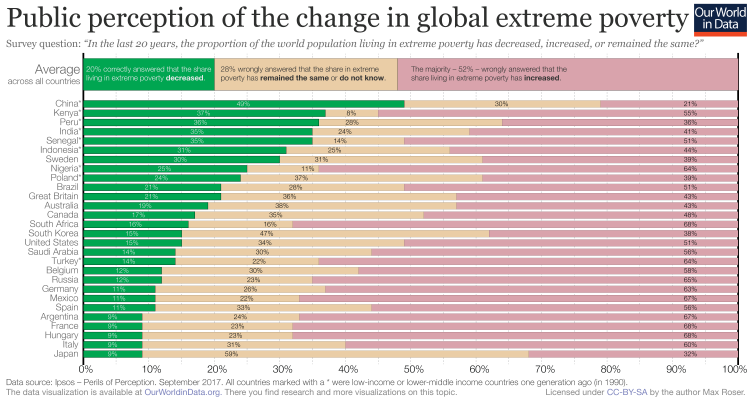

The first chart shows how the surveyed people answered the following question: “In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has decreased, increased, or remained the same?”

The majority of people – 52% – believe that the share of people in extreme poverty is rising. The opposite is true. In fact, the share of people living in extreme poverty across the world has been declining for two centuries and in the last 20 years this positive development has been faster than ever before (see our entry on global poverty). For the recent era it doesn’t even matter what poverty line you choose, the share of people below any poverty line has fallen (see here).

There are some people who answered the question correctly: every fifth person knows that poverty is falling. But it’s interesting that the share of correct answers differs substantially across countries. The countries I marked with a star are those that were a low-income or lower-middle-income countries a generation ago (in 1990). In these poorer countries more people understand how global poverty has changed. People in richer countries on the other hand – in which the majority of the population escaped extreme poverty some generations ago – have a very wrong perception about what is happening to global poverty.

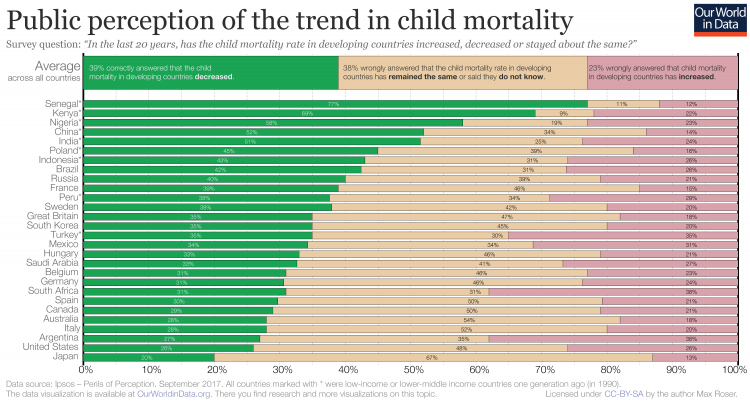

We are not just wrong about global poverty. In the same survey people were asked: “In the last 20 years, has the child mortality rate in developing regions increased, decreased or stayed about the same?”

Here again the data is very clear. The child mortality rate in both the less- and least-developed countries has halved in the last 20 years.6

The survey once more shows that most people are not aware of this. On average only 39% know that the mortality of children is falling. And what greater achievement has humanity ever achieved than making it more and more likely that children survive the first, vulnerable years of their lives and sparing parents the sadness of losing their babies? This has to be one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

And just as with knowledge about extreme poverty, the share of uninformed people is much higher in the rich countries of the world. So is our work at Our World in Data needed? This survey shows that few Senegalese or Kenyans will learn something new; but if you have some friends in the US or Japan you will probably help them if you share our work.

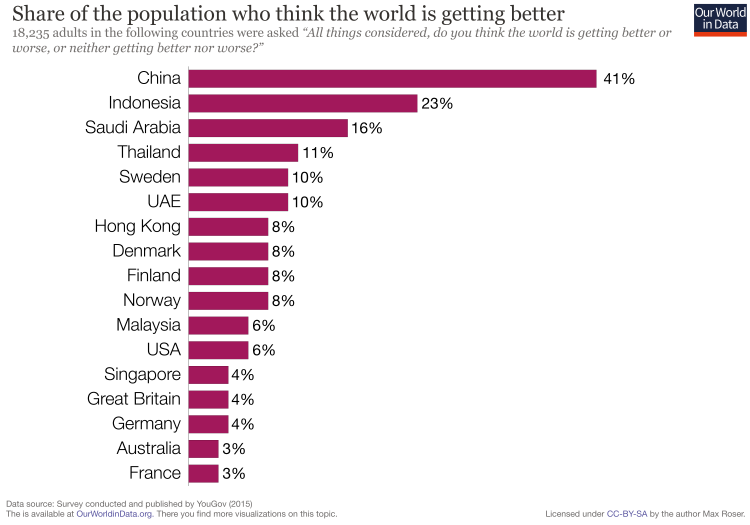

The widespread ignorance about these truly important changes in the world feeds into a general discontent about how the world is changing. When YouGov asked in a separate survey the more general question: “All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse?” there were very few who gave a positive answer. In France and Australia only 3%(!) think the world is getting better.

And again we see that in poorer countries the share of people who answer positively is higher.7

What should we make of the fact that many perceive the world to be stagnating or even declining in global health or poverty while we are in fact achieving the most rapid improvements in our history in these very same aspects?

First, this is simply sad. It means that we think worse of the world than we should. We think more poorly than we should about the time we are living in, and we think more poorly than we should about what people around the world are achieving right now.

Second it makes clear that we are doing a terrible job at understanding and communicating what is happening in the world. Particularly in rich countries the education systems and media are failing to convey an accurate perspective on how the world is changing – arguably one of the main expectations we should have of them.8

Our perception of how the world is changing matters for what we believe is possible in the future.

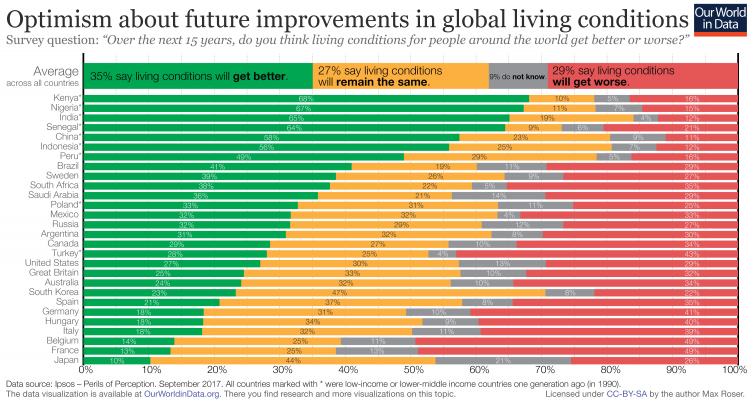

If we ask people about what is possible for the world, then most of us answer ‘not much’. This chart documents the survey answers to the question “over the next 15 years, do you think living conditions for people around the world get better or worse?”. More than half of the people expect stagnation or that things will be getting worse. Fortunately, the places in which people currently have the worst living conditions are more optimistic about what is possible in the coming years.

On the whole, the findings from the surveys are clear: we do not only believe that the world is stagnating or declining, we also expect that this perceived stagnation or decline will continue into the future.

This pessimism about what is possible for the world matters politically. Those who don’t expect that things get better in the first place will be less likely to demand actions that can bring positive developments about. The few optimists on the other hand will want to see the necessary changes for the improvements they are expecting.

Finally the survey suggests that there is a connection between our perception of the past and our hope for the future. This chart shows that the degree of optimism about the future differs hugely by the level of people’s knowledge about global development.

Those that were most pessimistic about the future tended to have the least basic knowledge on how the world has changed. Of those who could not give a single correct answer to the survey questions, only 17% expect the world to be better off in the future. At the other end of the spectrum, those who had very good knowledge about how the world has changed were the most optimistic about the changes that we can achieve in the next 15 years.

This is a correlation and as we know, correlation does not imply causation. To understand whether there is a causal link we would need to know whether getting a more accurate picture of how the world is changing makes one change one’s belief about what will happen in the future. Unfortunately I am not aware of a study that looked into this question.9

Of course no one can know how the future turns out and there is nothing that would make the progress we have seen in recent decades continue inevitably and not every global development pessimist is ill-informed. But what we do know from these surveys is that these two views go together: Those who are pessimistic are much more likely to have little understanding about what is happening in the world.

Obviously the question then is, why is it that better informed people are more optimistic about the future?

As we have seen, being wrong about global development mostly means being too negative about how the world is changing. Being wrong in these questions means having a cynical worldview. Cynicism suggests that nothing can be done to improve our situation and every effort to do so is bound to fail. Our history, the cynics say, is a history of failures and what we can expect for the future is more of the same.

In contrast to this, answering the questions correctly means that you understand that things can change. An accurate understanding of how global health and poverty are improving leaves no space for cynicism. Those who are optimistic about the future can base their view on the knowledge that it is possible to change the world for the better, because they know that we did.

Declinism

Declinism refers to the belief that a country or some other institution is in decline. Declinism was a prevalent feature of British political and economic history, whereby the decline of Britain as a world power was seen as the result of internal failures rather than international forces or global convergence. David Edgerton writes: “Declinism is beginning to appear as one of the last vestiges of imperial grandeur: for declinism holds, implicitly but clearly, that if Britain had done better it would have remained a much larger player on the world stage.”10

Today declinism in the United States is fashionable with many politicians. Donald Trump’s campaign slogan for the 2016 Republican nomination election was “Make America Great Again!”

The major flaw in much of the declinist narrative is the failure to distinguish between absolute and relative changes. Between 2010-14, US real GDP growth rates have fluctuated between 1.5-2.5% and yet, the US economy was recently overtaken by the Chinese economy measured in PPP-adjusted terms.11

In many ways this may capture the reason why the most developed nations tend to believe that their economy is in decline: relative decline is interpreted as absolute decline. Unsurprisingly, new EU member states tend to be much more optimistic about the future. The four largest economies — the UK, France, Germany and Italy — are the most pessimistic. This pattern persists when considering economies at different stages of development: developing countries are more optimistic about the future, while developed ones tend to be pessimistic.

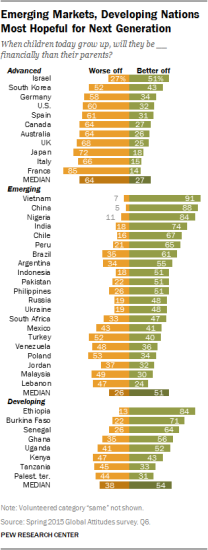

Optimism about the future of the next generation by country – Pew Research Center12

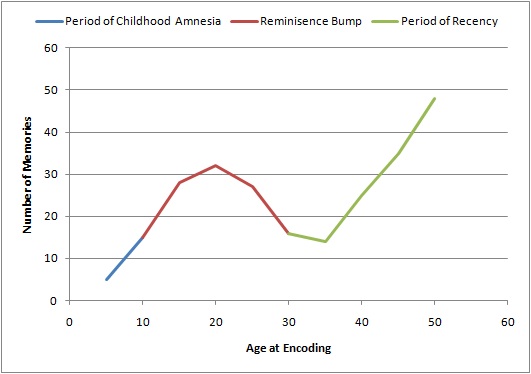

One interesting explanation for declinism is that it is the result of the way we encode memories and what we remember. Firstly, researchers have long established a robust pattern in the age at which we retain the most memories. In old age, memories from our lives are not evenly distributed but instead concentrated in two regions. These regions are (1) memories formed in adolescence and early adulthood, between the ages of 10-30, and (2) recent memory of events. The following figure is a useful representation of this distribution.

Secondly, research finds that as we get older we tend to have – on average – fewer negative experiences and that we are more likely to remember the positive ones over the negative ones.14

This effect combined with the reminiscence bump could explain why declinism exists among older generations, and why your parents could never stand the music you listened to! The universality of this effect is illustrated by Harvey Daniels with the use of these quotes about the decline of the English language15:

- “The common language is disappearing. It is slowly being crushed to death under the weight of verbal conglomerate, a pseudospeech at once both pretentious and feeble, that is created daily by millions of blunders and inaccuracies in grammar, syntax, idiom, metaphor, logic, and common sense…. In the history of modern English there is no period in which such victory over thought-in-speech has been so widespread. Nor in the past has the general idiom, on which we depend for our very understanding of vital matters, been so seriously distorted.” (A. Tibbets and C. Tibbets, What’s Happening to American English?, 1978)

- “From every college in the country goes up the cry, ‘Our freshmen can’t spell, can’t punctuate.’ Every high school is in disrepair because its pupils are so ignorant of the merest rudiments.” (C. H. Ward, 1917)

- “Unless the present progress of change [is] arrested…there can be no doubt that, in another century, the dialect of the Americans will become utterly unintelligible to an Englishman…” (Captain Thomas Hamilton, 1833)

- “Our language is degenerating very fast.” (James Beattie, 1785)

In the light of this research on human nature it is then not surprising that one of the earliest Sumerian tablets discovered and deciphered by modern scholars was a complaint by a teacher about his students’ writing ability.

Lifespan memory retrieval curve – Wikipedia13

There are three main reasons we should try to combat social pessimism and declinism. The first reason is simple; indicators of living standards are significantly improving around the world. By monitoring and researching these changes we can identify ways in which progress can be achieved. Over the long-run, say 50-100 years, human progress has been staggering with the benefits not confined to the richest or most powerful. The second reason is that if our perceptions of the reality are wrong, we can end up prioritising the wrong things and making ineffectual change. Finally, being optimistic can be good for your health, while having a pessimistic outlook can be detrimental to your health.

Perception and Priority

The public perception of these indicators matters because it directly influences the priorities of voters in democratic countries and politicians. If, as in the example above, the public believes crime is increasing, it is likely that it demands more policing not for a reason grounded in reality, but for an imagined worsening of the society they live it. This is one reason why incorrect public perceptions can be a problem.

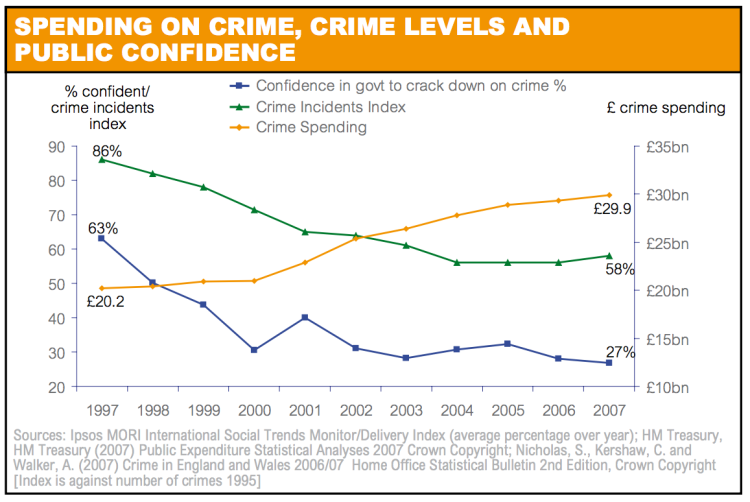

The following figures underline just how sizable these effects can be. The first shows how spending on crime has moved with the public’s confidence in the government’s ability to crack down on crime. As the public’s confidence fell, spending on crime increased and recorded crime fell; without any uptick in the public’s confidence.

Public confidence, recorded crime and government spending in the UK, 1997-2007 – Ipsos MORI (2008)16

One contributing factor to some of the widespread misinformation seems to be the content consumed through media channels.

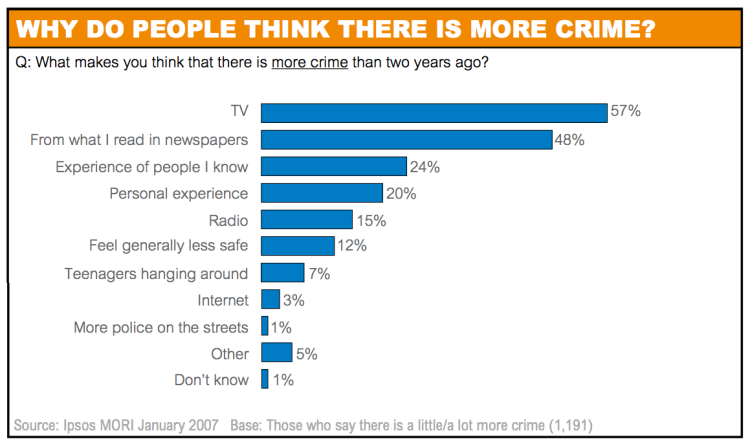

Of those who believed crime was increasing, more than half suggested that information on TV was a reason they believed there was more crime. In addition to this, almost half suggested that what they read in newspapers was a factor.

Research conducted by Stefano DellaVigna and Ethan Kaplan highlights the degree to which the media can influence voting behaviour.18

DellaVigna and Kaplan looked at how the introduction of Fox News between 1996 and 2000 in different towns affected voting patterns and turnout in the Presidential election of 2000. They find “a significant effect of the introduction of Fox News on the vote share in Presidential elections between 1996 and 2000. Republicans gained 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points in the towns that broadcast Fox News. Fox News also affected voter turnout and the Republican vote share in the Senate. Our estimates imply that Fox News convinced 3 to 28 percent of its viewers to vote Republican, depending on the audience measure. The Fox News effect could be a temporary learning effect for rational voters, or a permanent effect for nonrational voters subject to persuasion.”

Another dimension to this debate is the extent to which the perceived terrorism threat affects the willingness of individuals to trade-off civil liberties.19

Darren Davis and Brian Silver find that “the greater people’s sense of threat, the lower their support for civil liberties.” This effect is attenuated by the people’s trust in government but fairly consistent across nearly all political affiliations and demographics.

TV and newspapers are largest factors driving crime perceptions in the UK, 2007 – Ipsos MORI17

Things are getting better and it is good to know that

With all the negative news stories and sensationalism that exists in the media it may be hard to believe things are improving. These events can be contextualized as short-term fluctuations in an otherwise positive global trend.

Quantifying this progress and identifying its causes will help researchers develop successful strategies to combat the world’s problems. We discuss many important improvements in our history of global living conditions.

The relation between health and optimism

There is a large literature that links an optimistic outlook on life to positive health outcomes. While it is interesting to read and think about this, one should be prudent not to over-interpret these findings and consider carefully if it is possible to think of these relationships as causal:

Studies have found a link between an individual’s optimism/pessimism (measured by surveys) and their health outcomes. Julia Boehm and Laura Kubzansky reviewed over 200 published studies to investigate the link between a positive psychological outlook (optimism, life satisfaction and happiness) and cardiovascular health.20

They found that a positive psychological outlook was strongly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease: “For example, the most optimistic individuals had an approximately 50% reduced risk of experiencing an initial cardiovascular event compared to their less optimistic peers.”21

Boehm et al. (2011) also find a link between optimism and the composition of cholesterol in the blood. Optimistic individuals had higher levels of good cholesterol and lower levels of triglycerides.22

Further research using data from the Women’s Health Initiative found that over an eight year period, the most optimistic women had a 9% lower risk of developing coronary heart disease and a 14% lower risk of dying from any cause.23 Similar results were also found by researchers writing in the Archives of General Psychiatry; using data from the Netherlands, they found that the most optimistic individuals had a 55% reduced risk of all-cause mortality and a 23% reduced risk of cardiovascular death.

Dire predictions for the future are nothing new. Indeed we can go back centuries or even millennia and find plenty of examples of pessimistic accounts of the future of the world.

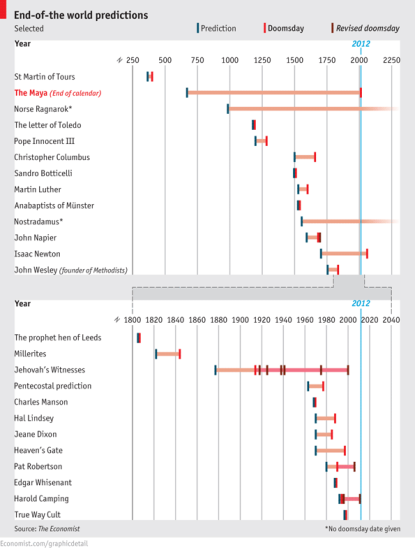

This infographic shows a series of predictions for the year in which the world will end – from religious figures to scientists like John Napier and Isaac Newton.

End of the world predictions – The Economist24

Predictions of dire futures are also common in fictional literature.

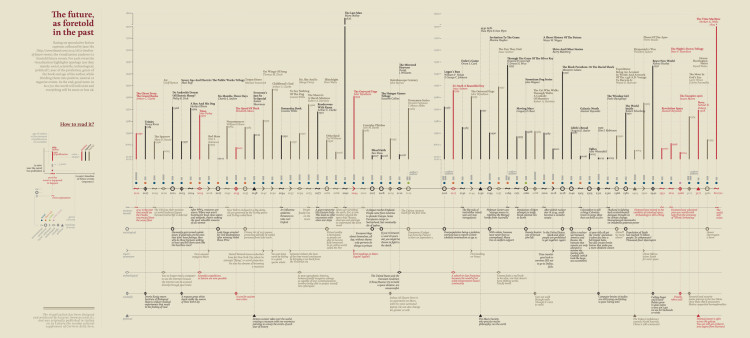

This beautiful visualization presents a time of predictions of the future as foretold in novels.

The future as foretold in the past – Giorgia Lupi and Accurat25