At Our World in Data we aim to bring together the empirical data and research to show how living conditions around the world are changing. Is that necessary?

The opinion research organization Ipsos MORI conducted a detailed survey of 26,489 people across 28 countries that gives us an answer.1

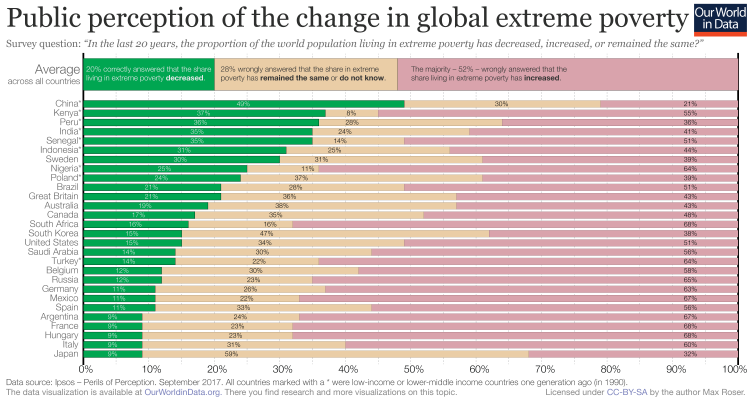

The first chart shows how the surveyed people answered the following question: “In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has decreased, increased, or remained the same?”

The majority of people – 52% – believe that the share of people in extreme poverty is rising. The opposite is true. In fact, the share of people living in extreme poverty across the world has been declining for two centuries and in the last 20 years this positive development has been faster than ever before (see our entry on global poverty). For the recent era it doesn’t even matter what poverty line you choose, the share of people below any poverty line has fallen (see here).

There are some people who answered the question correctly: every fifth person knows that poverty is falling. But it’s interesting that the share of correct answers differs substantially across countries. The countries I marked with a star are those that were a low-income or lower-middle-income countries a generation ago (in 1990). In these poorer countries more people understand how global poverty has changed. People in richer countries on the other hand – in which the majority of the population escaped extreme poverty some generations ago – have a very wrong perception about what is happening to global poverty.

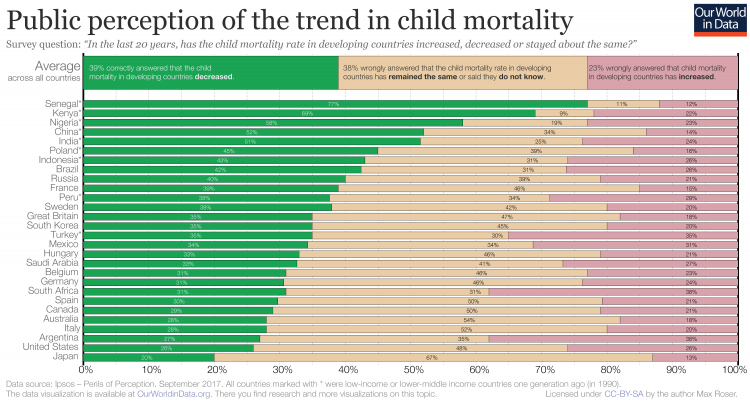

We are not just wrong about global poverty. In the same survey people were asked: “In the last 20 years, has the child mortality rate in developing regions increased, decreased or stayed about the same?”

Here again the data is very clear. The child mortality rate in both the less- and least-developed countries has halved in the last 20 years.2

The survey once more shows that most people are not aware of this. On average only 39% know that the mortality of children is falling. And what greater achievement has humanity ever achieved than making it more and more likely that children survive the first, vulnerable years of their lives and sparing parents the sadness of losing their babies? This has to be one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

And just as with knowledge about extreme poverty, the share of uninformed people is much higher in the rich countries of the world. So is our work at Our World in Data needed? This survey shows that few Senegalese or Kenyans will learn something new; but if you have some friends in the US or Japan you will probably help them if you share our work.

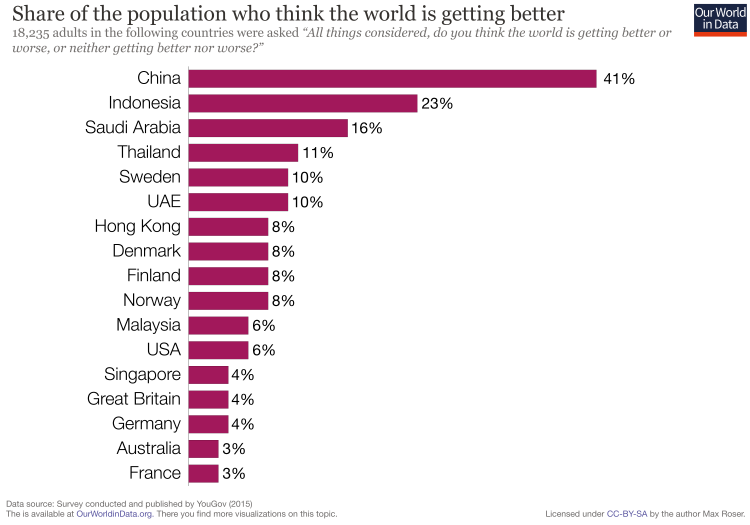

The widespread ignorance about these truly important changes in the world feeds into a general discontent about how the world is changing. When YouGov asked in a separate survey the more general question: “All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse?” there were very few who gave a positive answer. In France and Australia only 3%(!) think the world is getting better.

And again we see that in poorer countries the share of people who answer positively is higher.3

What should we make of the fact that many perceive the world to be stagnating or even declining in global health or poverty while we are in fact achieving the most rapid improvements in our history in these very same aspects?

First, this is simply sad. It means that we think worse of the world than we should. We think more poorly than we should about the time we are living in, and we think more poorly than we should about what people around the world are achieving right now.

Second it makes clear that we are doing a terrible job at understanding and communicating what is happening in the world. Particularly in rich countries the education systems and media are failing to convey an accurate perspective on how the world is changing – arguably one of the main expectations we should have of them.4

Our perception of how the world is changing matters for what we believe is possible in the future.

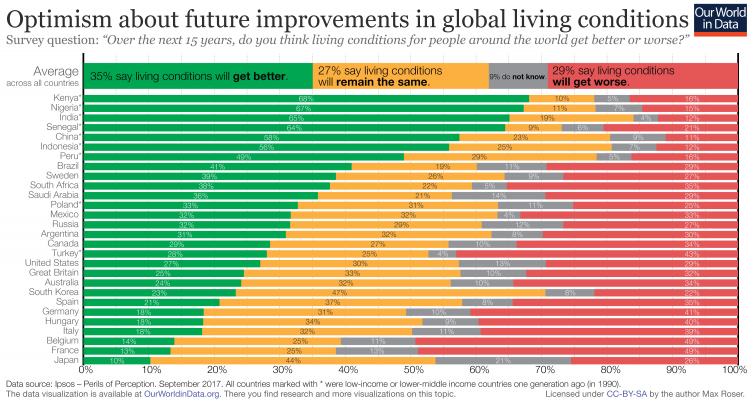

If we ask people about what is possible for the world, then most of us answer ‘not much’. This chart documents the survey answers to the question “over the next 15 years, do you think living conditions for people around the world get better or worse?”. More than half of the people expect stagnation or that things will be getting worse. Fortunately, the places in which people currently have the worst living conditions are more optimistic about what is possible in the coming years.

On the whole, the findings from the surveys are clear: we do not only believe that the world is stagnating or declining, we also expect that this perceived stagnation or decline will continue into the future.

This pessimism about what is possible for the world matters politically. Those who don’t expect that things get better in the first place will be less likely to demand actions that can bring positive developments about. The few optimists on the other hand will want to see the necessary changes for the improvements they are expecting.

Finally the survey suggests that there is a connection between our perception of the past and our hope for the future. This chart shows that the degree of optimism about the future differs hugely by the level of people’s knowledge about global development.

Those that were most pessimistic about the future tended to have the least basic knowledge on how the world has changed. Of those who could not give a single correct answer to the survey questions, only 17% expect the world to be better off in the future. At the other end of the spectrum, those who had very good knowledge about how the world has changed were the most optimistic about the changes that we can achieve in the next 15 years.

This is a correlation and as we know, correlation does not imply causation. To understand whether there is a causal link we would need to know whether getting a more accurate picture of how the world is changing makes one change one’s belief about what will happen in the future. Unfortunately I am not aware of a study that looked into this question.5

Of course no one can know how the future turns out and there is nothing that would make the progress we have seen in recent decades continue inevitably and not every global development pessimist is ill-informed. But what we do know from these surveys is that these two views go together: Those who are pessimistic are much more likely to have little understanding about what is happening in the world.

Obviously the question then is, why is it that better informed people are more optimistic about the future?

As we have seen, being wrong about global development mostly means being too negative about how the world is changing. Being wrong in these questions means having a cynical worldview. Cynicism suggests that nothing can be done to improve our situation and every effort to do so is bound to fail. Our history, the cynics say, is a history of failures and what we can expect for the future is more of the same.

In contrast to this, answering the questions correctly means that you understand that things can change. An accurate understanding of how global health and poverty are improving leaves no space for cynicism. Those who are optimistic about the future can base their view on the knowledge that it is possible to change the world for the better, because they know that we did.

Additional chart:

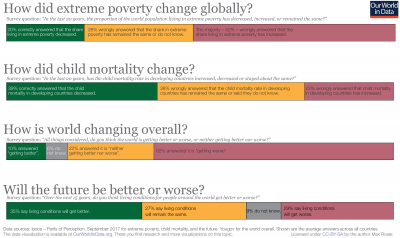

For a talk on this I made this summary of the charts above and I post it here in case you find it helpful.