How many farms are there?

The most recent estimate of the number of farms in the world is around 570 million.1

This figure – as the researchers stress – is a crude estimate that is likely to be lower than the actual number of farms for a few reasons. First, Lowder et al. (2016) make this estimate based on the latest agricultural census data from 167 countries which represent 96% of the world’s population, 97% of the population active in agriculture, and 90% of agricultural land. But, 40 smaller countries had no estimates and were not included. If they were included, this figure would be higher.

Second, the latest agricultural census data for many countries is outdated. The majority of these estimates come from census data from 1990, 2000 or 2010. However, in some countries, the latest census data is much older. For example, the latest census for Brunei, Nigeria and Zimbabwe was 1960. The number of farms in several countries is likely to have increase since then.

It’s therefore likely that this 570 million figure is a lower-bound estimate.

The number of farms in each country as of the latest agricultural census is shown in the map.

Average farm size by country

The chart and map here shown the distribution of the average farm size by country.2

In general we see a positive relationship between income and average farm size. Poorer countries tend to have smaller farms, and this increases towards middle and high incomes.

Distribution of farm size by country

How doe the distribution of farm sizes vary within a country?

In the charts we see the distribution by two measures. First, the number of farms of each size (in other words, the number of farms that are less than 1 hectare; 2 to 5 hectares etc.). Second, the distribution by agricultural area i.e. how many hectares in total fall within each farm size bracket.

We see large differences across the world. Lower-income countries tend to have many more smaller farms (less than 5 hectares, or even less than 1 hectare). High-income countries tend to have most farms in the range of tens to hundreds of hectares.

China is an important stand-out, being a middle-income country that is still dominated by lots of smallholder farms. In its last agricultural census, 93% of its farms were less than 1 hectare.

Globally – based on a sample of 111 countries and territories with a total of nearly 460 million farms – 72% of farms are smaller than one hectare in size; 12% are 1–2 ha in size; and 10% are between 2 and 5 ha. Only 6% of farms are larger than 5 hectares. Note that this is based on the number of farms and not their percentage of total agricultural area, which can give very different results. Despite accounting for only 16% of farms, those larger than 2 hectares account for 88% of the world’s farmland.3

How has the size of farms changed over time?

This map shows which countries have seen an increase, decrease or little change in the average farm size since 1960.

We see that most high-income countries have seen an increase in average farm size. In contrast, most low and middle-income countries have seen a decline, which more disaggregation of land into smallholder farms.

You can see the change in average farm size by country here.

What share of farms are smallholders?

This chart shows the share of farms that are defined as smallholders. The definition of a ‘smallholder farm’ can vary: some classify it as a farm less than one hectares; others as less than 2 hectares; or even 5 hectares.

Here we show the share of farms that are less than two hectares.

What share of agricultural land is owned by smallholders?

This chart shows the share of agricultural land that is operated as smallholder farms. A smallholder farm is defined as being less than two hectares.

Do smallholders produce different types of foods?

This chart shows the distribution of the types of foods grown by farm size. This data is sourced from Ricciardi et al. (2018), which mapped the distribution of global food production by farm size.4

The smallest farms (those less than 2 hectares) devote the largest percentage of their overall crop production to cereals. They also tend to grow more fruit, pulses and roots and tubers. Medium-sized farms tend to produce more vegetables and nuts. While the largest farms tend to produce more oilcrops (such as soybeans or oil palm).

How does the allocation of crops vary by farm size?

This chart shows the distribution of the allocation of crops to their end use by farm size. In other words, how much of crops grown are allocated towards human food, animal feed, and industrial uses such as biofuels. This data is sourced from Ricciardi et al. (2018), which mapped the distribution of global food production by farm size.5

The smallest farms (those less than 2 hectares) tend to allocate the greatest share – between 55% to 59% – of their crop production to direct human food.

As farm size increases, more production tend to be allocated towards animal feed and processing into other products. Farms in the range of 200 to 500 hectares allocated the greatest share towards animal feed (16% to 29%). The largest farms (greater than 1000 hectares) allocated 12% to 32% to processing.

Most (84%) of the world’s 570 million farms are smallholdings; that is, farms less than two hectares in size.6 Many smallholder farmers are some of the poorest people in the world. Tragically, and somewhat paradoxically, they are also those who often go hungry.

A shift towards small-scale farming can be an important stage of a country’s development, especially if it has a large working age population. But, it’s gruelling work with poor returns: small farms can achieve good yields but need lots of human labor and input.7 Labor productivity is low. This is why countries move beyond a workforce of farmers: younger people get an education, move towards cities, and try to secure a job with higher levels of productivity and income. A country cannot leave deep poverty behind when most of the population work as smallholder farmers.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has made incorrect claims about the world’s reliance on smallholder farmers in the past. One of its reports states that “small-scale farmers produce over 70% of the world’s food needs.”8 In other reports it has said that smallholder and family farms (which raises issues of how these terms are defined) produce 70-80% of the world’s food.9 This would mean that small farms produce nearly all of the world’s food. This has become a zombie statistic: one that has been repeated by many other organizations despite there being no evidence to support it.10

A key problem is that organizations – including the UN FAO – often use the terms ‘small farms’ and ‘family farms’ interchangeably. But they cannot, and should not be. As we will see later, these definitions give us very different estimates.

This confusion creates several problems. First, it creates a misunderstanding; one that might convince us that a world of smallholder farmers is what we need. If they produced nearly all of the world’s food, perhaps that is a future we would want to maintain. Second, it might make us concerned about the future of the global food system if countries move towards larger farms. As countries get richer, the average farm size tends to increase. If nearly all of the world’s food came from small farms, perhaps we should be worried about this development.

Is this concern justified? Researchers provide us with a better answer to this question of how much of the world’s food smallholders really produce.

How much of the world’s food do smallholder farmers really produce?

Several studies have tried to answer this question. The most extensive and recent comes from the work of Vincent Ricciardi and colleagues.11 They produced the first open dataset on global food production, mapped by farm size.12 It covers 154 crop types across 55 countries. It not only covers the amount produced across different farm sizes, but also the types of crops and what they are used for – whether they are eaten as food, used as animal feed, or for other uses such as biofuels.

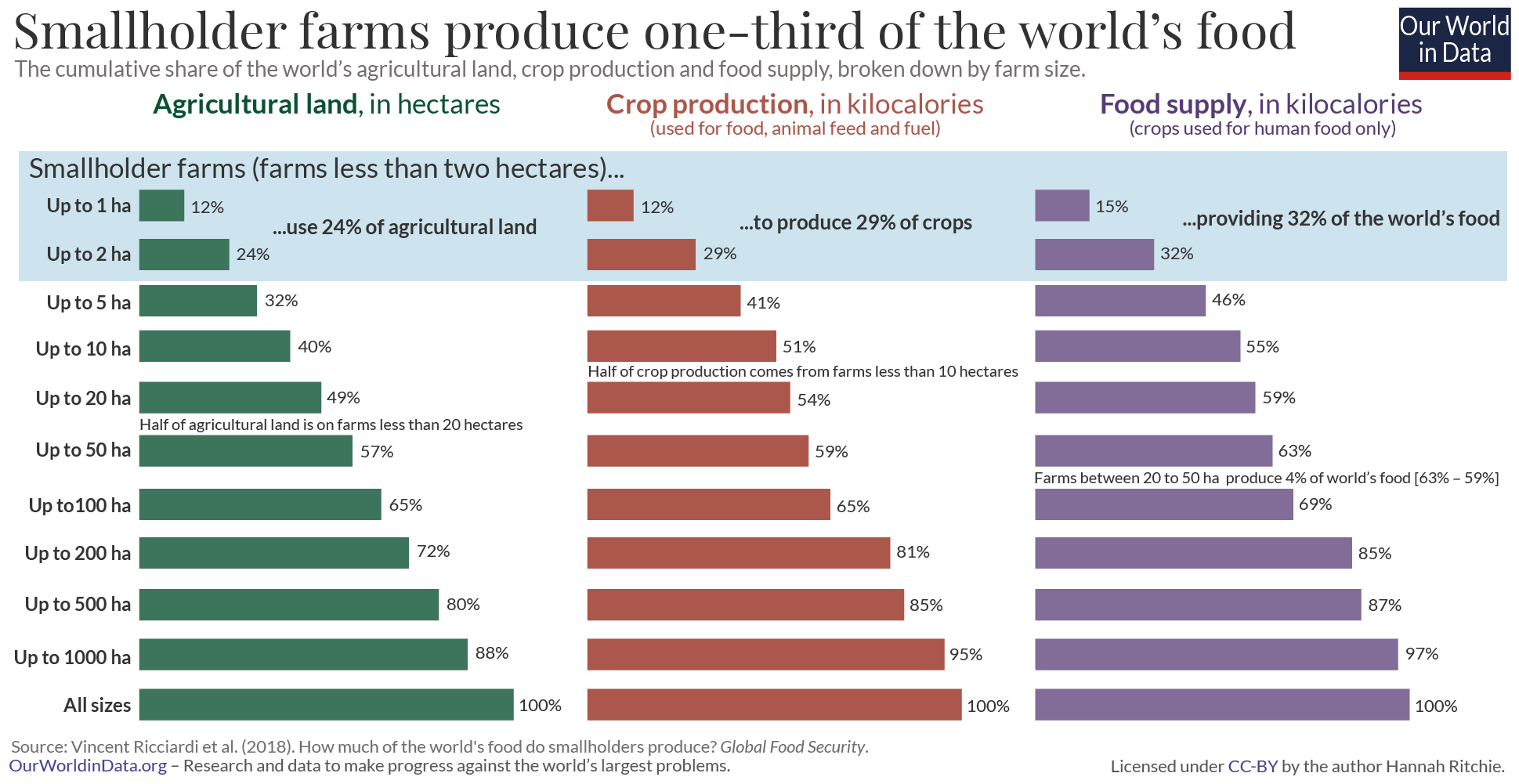

The chart shows their findings. This shows the cumulative total of three metrics – agricultural land; crop production; and food supply – with increasing farm size. So the top row of bars show the global total across farms less than one hectare; the second bar shows farms up to two hectares etc.

Smallholder farms are those that are less than two hectares.13 That’s the top two bars, which are shaded in blue.

Smallholder farmers produce 29% of the world’s crops, measured in kilocalories.14 Less than half of previous claims.

They do so using around one-quarter (24%) of the world’s agricultural land. They account for a bit more crop production than land use because smaller farms tend to achieve higher yields.15 This is very labor-intensive work; smaller farms get higher land productivity, but lower labor productivity.

These farms account for an even greater share of the world’s food supply – one-third (32%) of it.16 This is because smaller farms tend to allocate a larger share of their crops towards food, rather than animal feed or biofuels.

To get to the 70-80% figure that was previously reported, we would need to include farms all the way up to 100, or even 200 hectares. These results shown here are in line with other studies which agree that the figure of 70-80% is much too high.17

So while one-third of the world’s food is still a large share, it’s less than half of the widely-cited claim.

The claim that family farms produce 70-80% of the world’s food is likely to be true. A recent study by Sarah Lowder, Marco Sanchez, and Raffaele Bertini agrees with the conclusion that small farms produce one-third of the world’s food.18 But they also estimate the share produced on family farms. The definition of a family farm is broad: it’s one that is operated by an individual or group of individuals, where most labor is supplied by the family. This means they can be of any size – many family farms are large. Orders of magnitude larger than our under-two-hectare smallholders.

They find that family farms produce around 80% of the world’s food. To be clear: small farms produce one-third of the world’s food. Family farms – of any size – produce 80%. These terms should not be used interchangeably because they are very different.

Increasing the productivity of smallholder farming is a crucial step in countries transitioning from poverty to middle-incomes. Raising the output and incomes of smallholder farmers should be an important focus, even if they produced very little of the world’s food. This is because most of the world’s farms are smallholders, and they are some of the poorest people in the world.

We should avoid the romanticization of a future where most still spend their time working the fields for small returns. That would be a future where hundreds of millions continue to live in poverty.