Summary

In many countries the amount of time parents spend with their kids has been increasing over the last 50 years. This is true despite large changes in family structure over this time, such as a rise in single-parenting and a large increase in the share of women working outside the home. Looking carefully at the time parents spend with their kids and the forces that shape this time helps us understand an important aspect of family life and childhood development.

Over the last 50 years many countries have seen large changes in family structures and the institution of marriage. These changes – which include a rise in single-parenting and a large increase in the share of women working outside the home – have made some people worry that children might be getting ‘short-changed’, because parents are not spending as much time with them.

In 1999, for example, a report from the Council of Economic Advisors in the US analyzed trends over the second half of the 20th century and concluded: “The increase in hours mothers spend in paid work, combined with the shift toward single-parent families, resulted in families on average experiencing a decrease of 22 hours a week (14 percent) in parental time available outside of paid work that they could spend with their children.”

The line of thought behind these concerns is that changes to the structure of families and work have meant that children spend less time with parents, because parents – particularly mothers – spend less time at home.

Here we review the evidence and show that this reasoning is flawed. As we explain, in the US and many other rich countries parents spend more time with their kids today than 50 years ago. Equating ‘mother time at home’ with ‘children’s time with parents’ is a huge and unhelpful oversimplification.

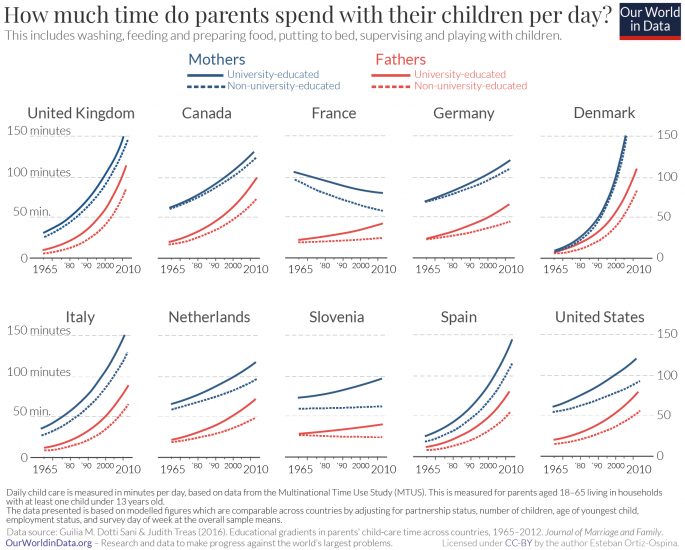

The chart here shows the time that mothers and fathers spend with their children. This is measured using time-use diaries where parents record the amount of time that they spend on various activities, including child care.

These estimates, which are sourced from a paper published in 2016 by sociologists Giulia Dotti Sani and Judith Treas, are disaggregated by education levels and are adjusted to account for demographic differences between countries. We explain below in more detail why these adjustments are important.1

As we can see here, there has been a clear increase in the amount of time parents spend with their children over the last 50 years. This is true for both fathers and mothers, and holds across almost all education groups and countries. The two exceptions are France, where mothers’ time has declined (from a very comparatively high level); and Slovenia where it has remained roughly constant among non-university-educated parents.

In terms of within-country inequalities we also see two clear patterns. First, in all countries mothers spend more time in child care activities than fathers. The differences are large and persistent across education groups. In some countries, such as Canada, France and the US, this gender gap has shrunk; while in other countries such as Denmark and Spain, the gap has widened.

Second, in all countries there is a positive ‘educational gradient’, meaning more educated parents tend to spend more time with their children. In many countries this gradient increased, and nowhere did it decline.

How much time do parents spend with their children per day?2

Digging Deeper: Raw vs Population-adjusted Trends in Time Use

The analysis above looked at time-use diaries from parents. But children may experience time and attention differently from adults. Is there evidence that children also feel they are getting more time with their parents?

In a study published in 2001 in the journal Demography, John Sandberg and Sandra Hofferth analyzed two surveys with data from child time-use diaries in the US, and found that children reported spending about 4.3 more hours per week with mothers, and 3 more hours per week with fathers in 1997 versus 1981.3

The data is sparse because time-use diaries for children are not very common; but the evidence that is available is consistent with what we’ve seen above: Children in the US agree that they’re spending more time with their parents than in the past.

The amount of time that parents spend with their children is determined by many factors, and working hours outside the home are only one of them. Choices, parenting norms, family size, and relationship ideals – for men and women, parents and children – matter a lot.

Several academic studies have dissected the data from the US in an attempt to disentangle the relative importance of different underlying factors. The conclusion from these studies is that the reason why we see an increase in the amount of time that American parents spend with kids is that many families, particularly those who are well-off, have been able to undergo changes in their routines and the allocation of tasks and time within the household, in order to spend more time with their children. Parents have been able to undergo ‘behavioral changes’ that have more than compensated for ‘structural changes’ that could have pushed in the opposite direction.4

Employment, and in particular working hours outside the home, determine a range of possible arrangements, but individual preferences and social conventions determine the actual allocation of time within that range of feasible options.

Preferences and social conventions are dynamic and change with time. There is a large academic literature that emphasizes the importance of parent-child interactions for children’s development, and it seems natural to allow for the possibility that in recent decades parenting norms have undergone considerable change in response to this scientific evidence.5

The available data shows that in many countries parents spend more time with their kids than ever before, and this is partly due to changes in social conventions and economic progress, especially declining working hours.

There are large differences between countries, and also large inequalities across different population groups within each country; but overall the trends tend to go in the same direction.

Of course, there’s a lot that is not being captured by these aggregate statistics. There are important distributional issues, and there is also clearly more to parents’ and children’s welfare than ‘total time spent together’. But despite these limitations, the available research and data still offers a clear lesson: contrary to what some people fear, it’s not the case that children in rich countries are being systematically ‘shortchanged’ by widespread changes in family structures.

Parents are spending more time with their kids than they used to, and this matters because parent-child interactions are important for childhood development.

Continue reading Our World in Data: