Summary

All energy sources have negative effects. But they differ enormously in size: as we will see, in all three aspects, fossil fuels are the dirtiest and most dangerous, while nuclear and modern renewable energy sources are vastly safer and cleaner.

From the perspective of both human health and climate change, it matters less whether we transition to nuclear power or renewable energy, and more that we stop relying on fossil fuels.

Two centuries ago we discovered how to use the energy from fossil fuels to make our work more productive. It was the innovation that started the Industrial Revolution. Since then, the increasing availability of cheap energy has been integral to the progress we’ve seen over the past few centuries. It has allowed work to become more productive, and people in industrialized countries are much richer than their ancestors, work much less, and enjoy much better living conditions than ever before. Energy access is therefore one of the fundamental driving forces of development. The United Nations rightly says that “energy is central to nearly every major challenge and opportunity the world faces today.”

But while energy from fossil fuels brought many benefits it unfortunately also has major negative consequences. There are three main categories of negative consequences.

The first is air pollution: at least five million people die prematurely every year as a result of air pollution.1

Fossil fuels and the burning of biomass – wood, dung, and charcoal – are responsible for most of those deaths. Eliminating fossil fuels could cut premature deaths from air pollution by around two-thirds. That’s three to four million deaths per year.2

The second is accidents. This includes accidents that happen in the mining and extraction of the fuels (coal, uranium, rare metals, oil and gas) and it includes accidents that occur in the transport of raw materials and infrastructure, the construction of the power plant, or their deployment.

The third is greenhouse gas emissions: fossil fuels are the main source of greenhouse gases, the primary driver of climate change. In 2018, 87% of global CO2 emissions came from fossil fuels and industry.3

All energy sources have negative effects. But they differ enormously in size: as we will see, in all three aspects, fossil fuels are the dirtiest and most dangerous, while nuclear and modern renewable energy sources are vastly safer and cleaner.

From the perspective of both human health and climate change, it matters less whether we transition to nuclear power or renewable energy, and more that we stop relying on fossil fuels.

Nuclear energy and renewables are far, far safer than fossil fuels

Today the global energy system is still dominated by fossil fuels, traditional biomass, hydropower and nuclear energy.4 However, modern renewables, such as solar and wind, are growing and we expect them to play an increasing role in our energy systems in the coming decades. As our energy systems transition we have decisions to make about what sources to choose. Safety concerns should be a key factor we consider.

How do fossil fuels, nuclear energy and renewables stack up in terms of safety?

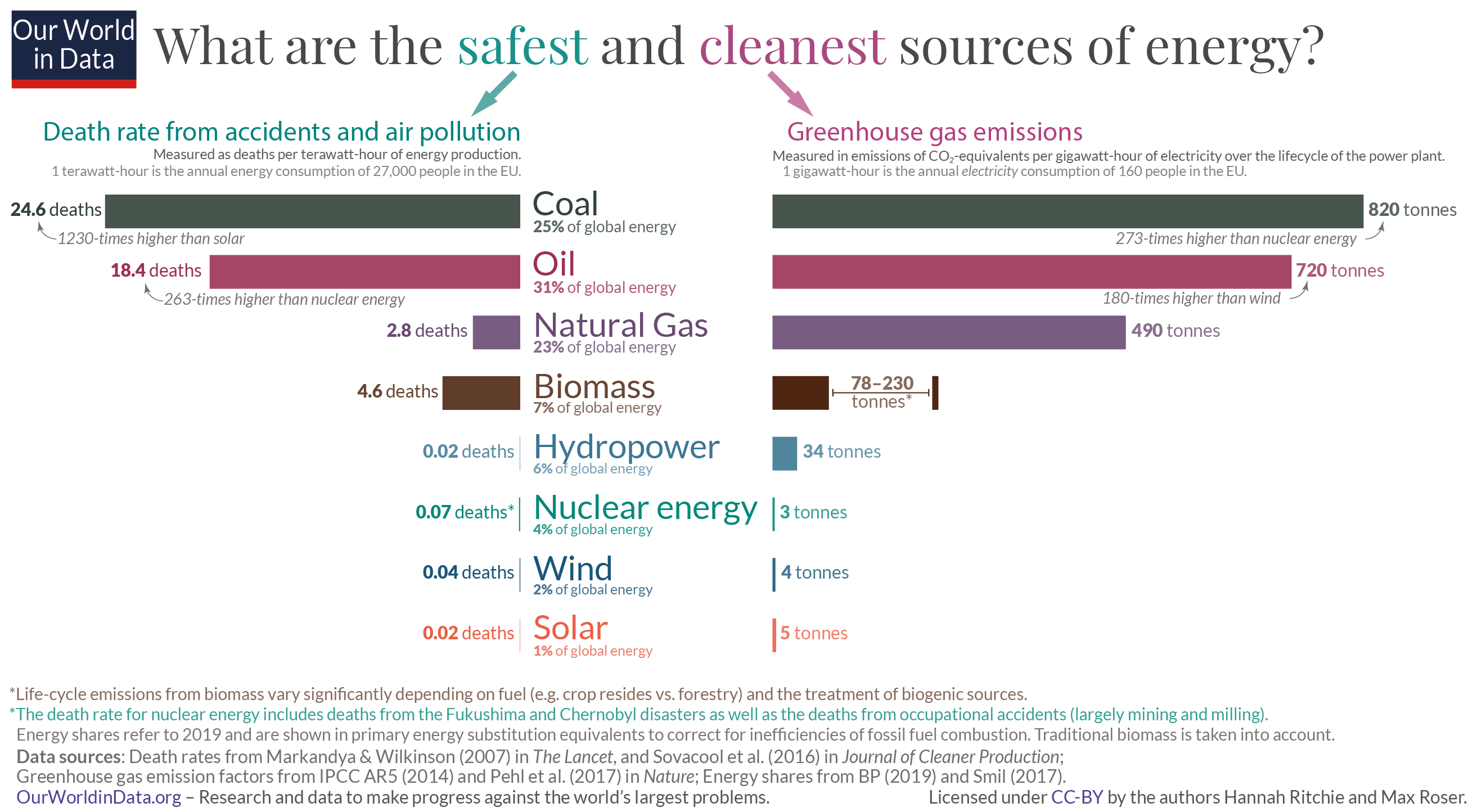

Research that answers this question comes from several sources. Anil Markandya and Paul Wilkinson (2007) published an analysis in the medical journal The Lancet, which compared the death rates from fossil fuels, nuclear, hydropower and biomass.5 In this study they considered deaths from accidents – such as the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, occupational accidents in mining or power plant operations – as well as premature deaths from air pollution.6 When they published the paper, modern renewable energy sources were still a very small source of energy production and weren’t included in the analysis. Data on the safety of renewable sources was published in a later study by Benjamin Sovacool and colleagues (2016).7,8 These figures of death rates from renewables are currently the best estimates we have to do this comparison, although they are undoubtedly not perfect [see footnote for more discussion].9 We’ve combined the results of these studies so we can compare death rates from all energy sources.

Later in this article we discuss in more detail how death rates from nuclear energy were derived. But to summarise: the death rate for nuclear includes an estimated 4000 deaths from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine (based on estimates from the WHO); 574 deaths from Fukushima (one worker death, and 573 indirect deaths from the stress of evacuation); and estimated occupational deaths (largely from mining and milling), as provided by Markandya and Wilkinson (2007).

In the chart we see the death rates of each – given as the number of deaths per terawatt-hour of energy.10 One terawatt-hour is about the same as the annual electricity consumption of 187,000 citizens in Europe.11

We see massive differences in the death rates of nuclear and modern renewables compared to fossil fuels.

Nuclear energy, for example, results in 99.8% fewer deaths than brown coal; 99.7% fewer than coal; 99.6% fewer than oil; and 97.5% fewer than gas. Wind, solar and hydropower are more safe yet.

Putting death rates from different energy sources in perspective

Looking at deaths per terawatt-hour can seem a bit abstract. So let’s try to put it in perspective.

Let’s consider how many deaths each source would cause for an average town of 187,090 people in Europe, which – as I’ve said before – consume one terawatt-hour of electricity per year. Let’s call this town ‘Euroville’.

If Euroville was completely powered by coal we’d expect 25 people to die prematurely every year as a result. Most of these people would die from air pollution. This is how a coal-powered Euroville would compare with towns powered by other energy sources:

- Coal: 25 people would die prematurely every year;

- Oil: 18 people would die prematurely every year;

- Gas: 3 people would die prematurely every year;

- Nuclear: In an average year nobody would die. A death rate of 0.07 deaths per terawatt-hour means it would take 14 years before a single person would die. As we will explore later, this might even be an overestimate.

- Wind: In an average year nobody would die – it will take 29 years before someone died;

- Hydropower: In an average year nobody would die – it will take 42 years before someone died;

- Solar: In an average year nobody would die – only every 53 years would someone die.

Contrary to popular belief, nuclear power has saved lives by displacing fossil fuels

Fossil fuels kill many more people than nuclear energy. We’ve seen this from the comparison above. This is surprising to many people, because many have prominent memories of the two major nuclear disasters in history: Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Unfortunately, public opinion on nuclear energy tends to be very negative.

In a separate article we take a look at the death toll of Chernobyl and Fukushima in detail. But we should at this stage summarise how the death rates for nuclear energy were calculated.

When we try to combine the two analyses referenced earlier, one issue we encounter is that neither study includes both of the major nuclear accidents in its death rate figure: Markandya and Wilkinson (2007) was published before the Fukushima disaster in 2011; and Sovacool et al. (2016) only look at death rates since 1990, and therefore do not include the 1986 Chernobyl accident. We have therefore reconstructed the death rate for nuclear to include both of these terrible accidents.12

For Chernobyl, there are several death estimates. We rely on the estimate published by the World Health Organization (WHO) – the most-widely cited figure – although this is considered to be too high by several researchers, including a later report by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR).13 We discuss this contention below. The WHO estimates that 4000 people have or will die from the Chernobyl disaster. This includes the death of 31 people as a direct result of the disaster and those expected to die at a later date from cancers due to radiation exposure.

The disaster in Fukushima killed 574 people. In 2018, the Japanese government reported that one worker has since died from lung cancer as a result of exposure from the event. No one died directly from the Fukushima disaster. Instead, most people died as a result of evacuation procedures. According to Japanese authorities 573 people died due to the impact of the evacuation and stress.14

To the death toll of history’s two nuclear disasters we have added the death rate that Markandya and Wilkinson (2007) estimated for occupational deaths, most from milling and mining. Their published rate is 0.022 deaths per TWh.

The sum of these three data points gives us a death rate of 0.07 deaths per TWh. We might consider this an upper estimate. Our estimated death toll from Chernobyl is based on the 2005/06 assessment from the WHO which applies a very conservative methodology called the linear no-threshold model. If you’re interested in the details of this we discuss it in more detail here. A later report by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) suggests that this overstates the risk of radiation-related deaths.15

Even with this upper figure, nuclear is still much much lower than the death rate from fossil fuels – 350 times lower than coal. Despite this, politicians have turned their backs on it in many countries.

Modern renewables and nuclear energy are not only safer but also cleaner than fossil fuels

So far we’ve only considered the short-term health impacts of these energy sources. But we need to also take into account their longer-term impact on climate change.

There is actually very good news: the safest sources for us today are the same sources that have the smallest impact on the climate. Sometimes the solutions to the large global issues we face come with trade-offs, but not here. Whether you are concerned about people dying now or the future of the planet, you want the same sources of energy.

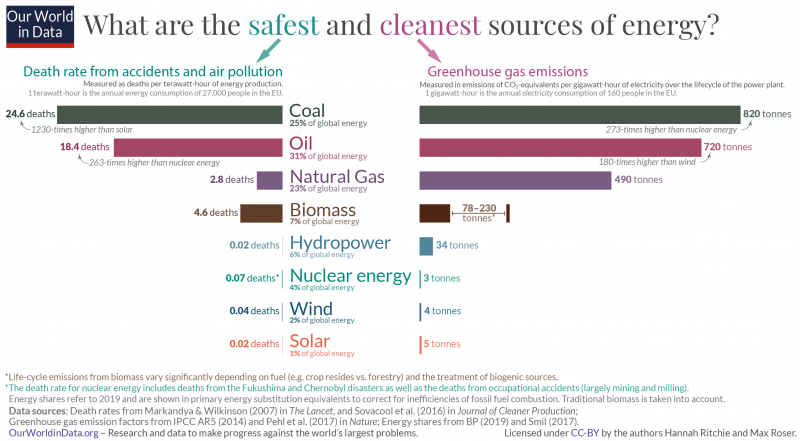

The visualization here shows this. On the left I have plotted the death rates per unit energy data we looked at previously and on the right you see their greenhouse gas emissions per energy unit. This measure of greenhouse gas emissions considers the total carbon footprint over the full lifecycle; figures for renewable technologies, for example, take into consideration the footprint of the raw materials, transport and their construction. I have adopted these figures as reported in the IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report, and more recent life-cycle figures by Pehl et al. (2017), published in Nature.16,17,18

The world is not facing a trade-off – the safer energy sources are also the least polluting. We see this from the symmetry of the chart. Coal causes most harm on both metrics: it has severe health costs in the form of air pollution and accidents, and emits large quantities of greenhouse gas emissions. Oil, then gas, are better than coal, but are still much worse than nuclear and renewables on both counts.

Nuclear, wind, hydropower and solar energy fall to the bottom of the chart on both metrics. They are all much safer in terms of accidents and air pollution and they are low-carbon options.

Unfortunately they still account for a very small share of global energy consumption – less than 10% of primary energy. Each source’s share of global primary energy production in 2019 (including traditional biomass in the total) is shown in the centre. Fossil fuels have so far dominated our energy systems for a couple of reasons: they kickstarted the Industrial Revolution and since then much of our energy infrastructure has been built around them. This early investment in fossil fuels means they have for a long time been relatively cheap – cheaper than many modern renewables in their infancy. But today, if we factor in the total costs of fossil fuels – not only the energy costs but also the social cost to our health and the environment – they are much more expensive than the alternatives. If we were to impose a carbon tax – which would account for the total costs that we all suffer – this would be the case.

Fortunately, clean and safe renewable technologies are becoming economically-competitive in their own right. The market price of both solar and wind has been falling rapidly meaning there is a real chance for change.

There is fierce debate about which low-carbon energy technologies we should pursue. But on the basis of three key questions – human health, safety and carbon footprint – nuclear and modern renewables do clearly best. A number of studies have found the same: there are large co-benefits for human health and safety in transitioning away from fossil fuels, regardless of whether you replace them with nuclear or renewables.19

The air pollution that fossil fuels cause is killing millions of people every year, and endanger many more from the future risks of climate change. We must shift away from them. And we can, we have better alternatives.