Unsafe water is one of the world’s largest health and environmental problems – particularly for the poorest in the world.

The Global Burden of Disease is a major global study on the causes and risk factors for death and disease published in the medical journal The Lancet.1 These estimates of the annual number of deaths attributed to a wide range of risk factors are shown here. This chart is shown for the global total, but can be explored for any country or region using the “change country” toggle.

Lack of access to safe water sources is a leading risk factor for infectious diseases, including cholera, diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio.2 It also exacerbates malnutrition, and in particular, childhood stunting. In the chart we see that it ranks as a very important risk factor for death globally.

According to the Global Burden of Disease study 1.2 people died prematurely in 2017 as a result of unsafe water. To put this into context: this was three times the number of homicides in 2017; and equal to the number that died in road accidents globally.

An estimated 1.2 million people died as a result of unsafe water sources in 2017. This was 2.2% of global deaths.

In low-income countries, it accounts for 6% of deaths.

In the map here we see the share of annual deaths attributed to unsafe water across the world. In 2017 this ranged from a high of 14% in Chad – around 1-in-7 deaths – to less than 0.01% across most of Europe.

When we compare the share of deaths attributed to unsafe water either over time or between countries, we are not only comparing the extent of water access, but its severity in the context of other risk factors for death. Clean water’s share does not only depend on how many die prematurely from it, but what else people are dying from and how this is changing.

Death rates from unsafe water sources give us an accurate comparison of differences in its mortality impacts between countries and over time. In contrast to the share of deaths that we studied before, death rates are not influenced by how other causes or risk factors for death are changing.

In this map we see death rates from unsafe water sources across the world. Death rates measure the number of deaths per 100,000 people in a given country or region.

What becomes clear is the large differences in death rates between countries: rates are high in lower-income countries, particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Rates here are often greater than 50 deaths per 100,000 – in the Central African Republic and Chad this was over 100 per 100,000.

Compare this with death rates across high-income countries: across Europe rates are below 0.1 deaths per 100,000. That’s a greater than 1000-fold difference.

The issue of unsafe sanitation is therefore one which is largely limited to low and lower-middle income countries.

We see this relationship clearly when we plot death rates versus income, as shown here. There is a strong negative relationship: death rates decline as countries get richer.

What share of people have access to safe drinking water?

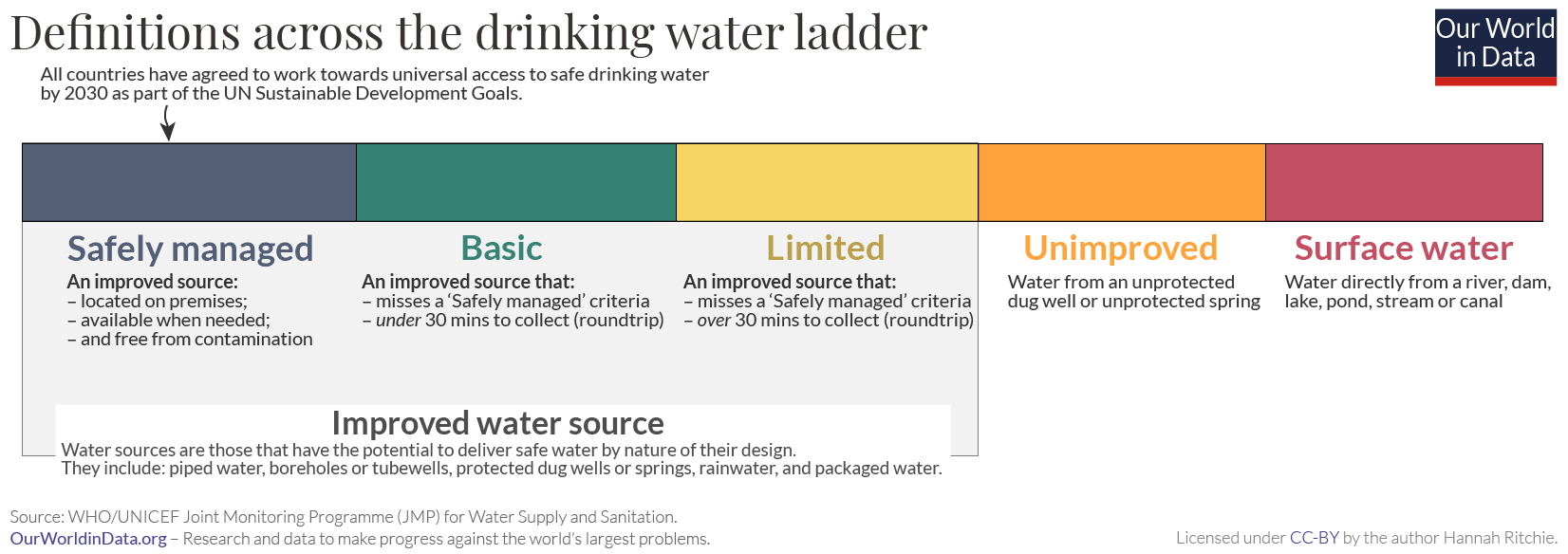

SDG Target 6.1 is to : “achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all” by 2030.

Where are we today? In 2020, almost three-quarters (74%) of the world population had access to a safely managed water source. One-in-four people do not have access to safe drinking water.

In the chart we see the breakdown of drinking water access globally, and across regions and income groups. We see that in countries at the lowest incomes, less than one-third of the population have safe water. Most live in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Are we making progress? The world has made progress in the last five years. Unfortunately, this has been very slow. In 2015 (at the start of the SDGs) only 70% of the global population had safe drinking water. That means we’ve seen an increase of four percentage points over five years.

This is obviously far too slow to reach universal access by 2030. If progress continues at these rates, we would only reach 82% by 2030. If we’re to meet our target we need to see rates of progress more than triple (increase 3.2-fold) for the coming decade.3

In the map shown we see the share of people across the world that have access to safe drinking water.

How many people do not have access to safe drinking water?

In the map shown we see the number of people across the world that do not have access to safe drinking water.

What share of people do not have access to an improved water source?

The definition of an improved drinking water source includes “piped water on premises (piped household water connection located inside the user’s dwelling, plot or yard), and other improved drinking water sources (public taps or standpipes, tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater collection).” Note that access to drinking water from an improved source does not ensure that the water is safe or adequate, as these characteristics are not tested at the time of survey. But improved drinking water technologies are more likely than those characterized as unimproved to provide safe drinking water and to prevent contact with human excreta.

In 2020, 6% of the world population did not have access to an improved water source.

In the map shown we see the share of people across the world that do not have access to improved water sources.

How many people don’t have access to an improved water source?

In the map shown we see the number of people across the world that do not have access to an improved water source.

Access to improved water sources increases with income

The visualisation shows the relationship between access to improved water sources versus gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. We see that there is a general link between income and freshwater access.

Typically most countries with greater than 90% of households with improved water have an average GDP per capita of more than $10,000-15,000. Those at lower incomes tend to have a larger share of the population without access. However, there are some notable exceptions: for example, more than half of Equatorial Guinea’s population lacks access to improved water despite having an GDP per capita above $27,000. In this case, the country’s wealth is highly concentrated; the mean GDP per capita is therefore far from the median GDP (i.e. there are high levels of inequality). Equatorial Guinea is one of the few remaining autocracies in the African continent. Its politics and governance therefore has a much stronger influence than average income.

Although income is an important determinant, the range of levels of access which occur across countries of similar prosperity further support the suggestion that there are other important governance and infrastructural factors which contribute. For example, Malawi has achieved a 90% access rate despite having a GDP per capita just over $1,000. Mozambique which has a similar income levels has just over 50% access.

Rural households often lag behind on water access

In addition to the large inequalities in water access between countries, there are can also be large differences within country. In the charts we have plotted the share of the urban versus rural population with access to improved water sources and safely managed drinking water, respectively. Here we have also shown a line of parity; is a country lies along this line then access in rural and urban areas is equal.

Since nearly all points lie above this line, with very few exceptions — notably Palestine — access to improved water sources is greater in urban areas relative to rural populations. This may be partly attributed to an income effect; urbanization is a trend strongly related to economic growth.4

The infrastructural challenges of developing municipal water networks in rural areas is also likely to play an important role in lower access levels relative to urbanised populations.

Improved water source: “An improved drinking water source includes piped water on premises (piped household water connection located inside the user’s dwelling, plot or yard), and other improved drinking water sources (public taps or standpipes, tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater collection).”

Access to drinking water from an improved source does not ensure that the water is safe or adequate, as these characteristics are not tested at the time of survey. But improved drinking water technologies are more likely than those characterized as unimproved to provide safe drinking water and to prevent contact with human excreta. While information on access to an improved water source is widely used, it is extremely subjective, and such terms as safe, improved, adequate, and reasonable may have different meanings in different countries despite official WHO definitions. Even in high-income countries treated water may not always be safe to drink. Access to an improved water source is equated with connection to a supply system; it does not take into account variations in the quality and cost (broadly defined) of the service.” 5

Safely managed drinking water: “Safely managed drinking water” is defined as an “Improved source located on premises, available when needed, and free from microbiological and priority chemical contamination.”

‘Basic’ drinking water source: an “Improved source within 30 minutes round trip collection time.”

‘Limited’ drinking water source: “Improved source over 30 minutes round trip collection time.”

‘Unimproved’ drinking water source: “Unimproved source that does not protect against contamination.”

‘No service’: access to surface water only.